A few years back, I met Jonny Trunk in a pub in Stoke Newington on a sunny afternoon to talk about The Wicker Man. Jonny is one of the most inspiring men you could hope to waste an afternoon in the pub with – both a font of pop culture knowledge and a great raconteur. Basically, three or four pints very well spent.

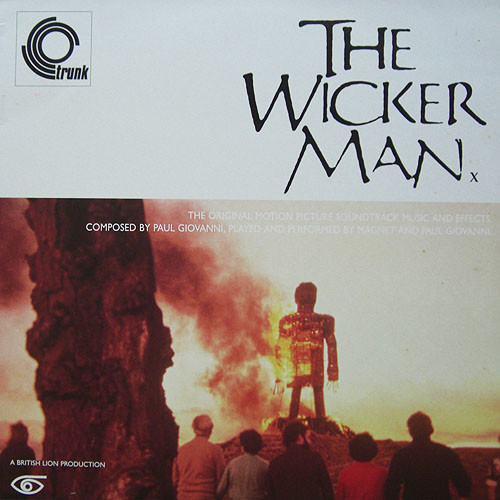

Many years prior to us meeting, Jonny had released the soundtrack to that film on his nascent Trunk label after a painstaking search for the copyright holders and the master tapes. I’d been obsessed with that soundtrack for a long time and knew the story behind it was almost as convoluted as that of the film, yet it hadn’t really been told in Allan Brown’s brilliant account of the film’s troubled path to cult status Inside The Wicker Man. I wanted to find out how something that had ended up subtly shifting the goal posts of music had come about – arguably kickstarting the ’00s folk revival that spawned everything from festivals to stadium bands – so I asked Jonny to tell the story of how the record came together.

I’m still not sure who I did this interview for, or if it ever got published anywhere at the time. A couple of nights ago, I had one of those infuriating 3am wide-awake moments where I was struck with the thought, “We have to celebrate The Wicker Man on May Day”. Thankfully I remembered this interview, which I reread and really liked. Hope you enjoy.

Robin Turner

Tell us a little about how you got started.

In the late ’80s and early ’90s I was part of a new wave of record collectors. This was the time when the record collector price guide would have everything apart from film music, library music, easy listening. Record collecting was your classic rock records. Early rock’n’roll, Beatles rarities, odd prog records. We came along and asked, “Where are all these weird electronic records done in the early ’60s… or the funny music we heard on the telly or in films”. We grew up in a time when the BBC showed odd, brilliant films late at night. They’d bought a bulk load of films to show midweek and they’d also show a late-night continental movie in the middle of the week. That could be a slightly weird gangster film or a film where a woman took her clothes off. If you were watching that on a B&W portable upstairs at a certain age it was going to end up having a very profound affect on you! So there was a bunch of us, all at a similar age who had similar tastes and ideas about where interesting music came from. And generally it wasn’t a rock record we were looking for – it was something we’d heard on telly or in a film, things that had affected us as teenagers.

So at record fairs, were you looking for things you knew or discovering things?

Bit of both. Take the 1968 Peter Sellers film The Party. I loved the film and had to find the music because I thought if I was ever going to have a party, I wanted that music playing. When I moved to London, I realised there were shops like 58 Dean Street that specialised in film music and there were people frequenting those shops who had similar tastes. Even though it was on Dean Street, it felt off the beaten track. You spent time in there and quickly worked out how things cross-referenced. People had done multiple scores; there were electronic records that sounded alike. Back then, if there was a film record with Raquel Welsh on it, I’d buy it because I figured if it had her on the cover it must be a pretty groovy record. I became so deeply into film music at an early age that by the early ’90s I’d worked out all of the things that didn’t seem to properly exist in the real world. The Monkees Head was one; it was like it had never happened. By the mid ’90s I’d started to try to find things I really wanted but couldn’t get hold of. Harold and Maude… that record didn’t exist apart from on a weird Japanese press that was incredibly hard to find. And that obsession was where The Wicker Man came in.

How did you come to the film originally?

It was the first film shown on Alex Cox’s Moviedrome series on the BBC2 in 1988. If you’d done a Top 100 British films around that point, the Wicker Man would not have been in it. Without that series and Alex Cox’s monologue beforehand, The Wicker Man and lots of films that were languishing in obscurity would not have had a reappraisal. Everyone had a video recorder back then, these were films that you’d end up watching round someone’s house after the pub. The Wicker Man was one we’d watch and laugh our heads off at. Because I think it’s a very funny film for lots of different reasons. And it’s also quite violent, quite unpleasant and has completely brilliant music. There’s really nothing else like it, it’s completely nuts.

I saw it described in Sight and Sound as the Smile of movies. And I saw that much more than the old Cinefantastique line about ‘the Citizen Kane of horror movies’.

I went to see the final cut of it the other day and people were laughing out loud. It’s hilarious and weird. Robin Hardy was doing a Q&A after it and he referred to it as a black comedy. That was the first time I’ve heard him say that and I’ve done events with him in the past.

Was there a soundtrack album at the time of release?

No. 58 Dean Street was run by the two Mashter brothers and this old Scottish guy called Graham. I used to go in and ask for records and he was very camp and pretty authoritative. I went in asking for Harold and Maude and the brothers would say “It doesn’t exist” and he’d pipe up “Oooh, I’ve seen it. It’s got a yellow cover.” And he was right. When I asked for The Wicker Man, he was pretty certain he’d never seen it. There were rumours based on an interview in Cinefantasique magazine where Robin Hardy had said that the soundtrack album had been planned but no one had ever seen it. Actually I think maybe he’d actually said he’d seen a copy and that was what sent me off on this mad hunt. People you’d talk to about trying to find it were very encouraging, people knew it was an incredible piece of work. Lots of strange stories started to emerge but at the heart of it, people who you spoke to about it didn’t have a clue why it didn’t exist as a record.

Do you think the success – or not – of the film itself would have meant that the music was never issued?

It was a B-movie. There was never any money behind the film apart from the money that paid for it to be made. And who was Paul Giovanni, why would anyone be interested? It came at a time when folk was popular but being overtaken by beardy, proggy rock. Add to that the fact that the British very rarely made film soundtrack records. Most soundtrack records are American, French, Italian. The only thing that could have made an impact at the time was something like The Italian Job but that did so badly in the UK you never ended up seeing it. Mainly because the cover was so bad. We never really had a soundtrack industry in the UK. For a B-movie like The Wicker Man, an LP would never have been made. It would be much more likely that there would be a 7” issued to go with it rather than an LP of cues.

What point did you think if this record is going to come out I’m going to have to do it myself?

The Trunk label didn’t exist. The first record we put out was The Super Sounds of Bosworth which came out in 1995. That came from me trying to buy music I’d become obsessed with, which was the kind of music that soundtracked Open University programmes on telly. The kind of music you’d get on a programme at three in the morning where a bloke in a brown corduroy jacket was talking about microbes or plankton. I didn’t realise back then that this was library music. After accidentally finding some library music, I went and spoke to the people who owned that music and I made the Bosworth record. That coincided with a quest to find this obscure film music. The Wicker Man was the key one for me mainly because there was this sequence in there, The Loving Couples track. It’s a Gently Johnny instrumental. And for me that was what it was all about. I love albums but I get really obsessed with one or two minute fragments of music like that. That Loving Couples sequence is incredibly beautiful. And it’s associated with lots of people having sex in the open air, which is obviously brilliant in itself!

Driven on by the desire to have that as a record – to be able to put a needle on that track whenever I wanted – that was the driving force behind seeking it out. I kept speaking to lots of different people about it, kept getting given different phone numbers and names. I eventually got to Lumiere who were based in Pinewood and they owned the film. They were really helpful but after a sequence of calls and faxes, Lumiere got sold and sold again and eventually it was bought by Canal Plus. At that point, who the fuck do you talk to? I remember phoning this number every day for what seemed like months and no-one ever answered then one day someone picked up the phone. “Hallo?” It was a woman in Paris who helped massively.

She found out the music was owned by Paul Giovanni who was dead. No one knew he was dead at this point. This is pre-internet; there’s no flow of information like there is now. I’d been trying to track him for ages so knew he wasn’t going to turn up with a few phone calls. So I asked if they would be up for us pressing a thousand copies each vinyl and CD of the soundtrack then holding any royalties due for Giovanni should he pop up. And she said yes. And I went absolutely fucking mental. From there, I got permission to go to the vaults at Pinewood where The Wicker Man archive was. In that vault was a gardening tray full of slides – most of which were rubbish – possibly a press book and some two inch reels. Amongst them was the M&E – the music and effects reels. There were thirteen reels of it in total. They dragged that out, put reel number one on this huge great reel to reel machine, much bigger than the kind you’d find in a recording studio, and they clicked it on. And it just slowly grinded up to speed and a voice came out. “I was born in the low countries…” It was a very odd moment. Four years of trying to find it and there I was at the only audio source. I got them couriered to the only studio in Soho that could transfer those kinds of reels to DAT. And from there we made The Wicker Man record.

How many records were there on Trunk at that point?

This was the third release but I’d started looking before the Bosworth record. If things hadn’t taken four years it would have been the first release.

So that soundtrack was part of the major motivation behind the label?

Yes. Purely selfishly.

Did you think you might press a thousand and end up selling five hundred or so?

I had no idea whatsoever. I knew the film had a funny following. I’d heard an interesting version of Willow’s Song by the Mock Turtles. They’d released an EP in the early ’90s called Wicker Man, that song was on there. Then the Sneaker Pimps did a version too. Back then Trunk wasn’t just me – it was Stephen Cracknell from the Memory Band, a guy called Ralph who was a Dylan nut and a record collector and Paul Lambden who eventually put out the Vashti Bunyan record on his label Spinney. We were really into weird film music and electronics and Paul was really into what we used to call Diddly which was a version of folk that seemed to have fallen off the map. The Wicker Man seemed to click everything together. The Bosworth record was interesting because it wasn’t like anything else before it – a bit electronic, a bit avant garde, a bit rocky, a bit jazzy… I thought it would unite all these people… people who liked Stereolab, people who liked jazz. Our idea was that if we connected all these people together we’d sell more records!

Pretty quickly The Wicker Man record gathered its own momentum. Mojo put it in their Nuggets section then shortly after release when one vinyl copy sold in Croydon for £150. An obscene amount of money. The run sold out incredibly quickly and the CD was bootlegged. You know if you’ve got the bootleg because it’s got no booklet. We should have gone back and asked to press more but we weren’t really in a position to do it. Also, there was Gary Carpenter – the associate music producer on the film – saying it wasn’t an official record. Every piece we did about the soundtrack he would write a strongly worded letter to the paper or magazine and say we were bootleggers. We had permission from the rights owners, our release was official. I think Bob Stanley interviewed Gary Carpenter about it and he said there was a copy of the soundtrack in a ‘secret place’. That was his shed. He had a tape that was an instrumental sync reel of all the tracks people singalong to like The Landlord’s Daughter and The Tinker of Rye. He told Bob he wanted £40,000 for the rights to his tapes even though he had no rights. A couple of years later, Silver Screen asked if they could combine our version and his version to make a second version of the soundtrack. They’d licensed it from British Lion and were prepared to take on legal matters on behalf of the Paul Giovanni estate.

Presumably the version that you released was the soundtrack to the short cut of the film?

Which is why there’s no Gently Johnny on it. We had people writing to us in disgust going, “Why is there no Gently Johnny on it you bastards?” You try spending four fucking years of your life trying to track down the right person to speak to. Do it yourself, you tosser! There were people thinking we took it from the VHS. It attracted a lot of weirdo Wicker Man hipsters who had big ideas and conspiracies about what had gone down.

https://buynoprescriptionrxxonline.net/lawrence-walter-pharmacy.html

https://buynoprescriptionrxxonline.net/overnight-drug-delivery.html

https://buynoprescriptionrxxonline.net/overnight-pharmacy-usa.html

Was this the point at which you became a proper label, when madmen started getting in touch?

Starting a proper label had never even crossed my mind. I just thought it was great that we’d sold all our records and had a bit of attention. And what’s next? Without that issue of the soundtrack (rather than the Silver Screen one) we wouldn’t have had the British folk revival. Something like the Green Man Festival couldn’t have happened without that issue. A band like Mumford and Sons wouldn’t conceivably have got anywhere without it.

We were the first DJs at the first Green Man. One hundred and thirty-five people. We’d started this funny club called Folkie Doakie. We’d hire an old pub and get games like skittles and apple bobbing. We described the night as ‘Old Folk and Dumplings’. That meant we would play old folk records and eat stew and dumplings and get absolutely battered. The music was proper hardcore folk. Apart from people like Eliza Carthy and the Folk and Roots scene that was there anyway, there was nothing that anyone outside of that scene related to.

It properly cut into the mainstream…

I think that film and its music had an enormous influence. When the record came out, you’d open the Sunday Times and there would be a full-page picture of the burning wicker man. They talked about how people had sent me pieces of the leg stumps and all sorts of things. And at the same time, you couldn’t bloody see the thing. The Wicker Man had a profound musical affect. I remember trying to make this folk electronic music in the mid ’90s; I was in the studio trying to work an Anne Briggs record with electronics and it was horrible. I’d thought a lot about how no one had tried to modernise folk back then; it was a genre that had been left alone. It was like it hadn’t really been considered. A missing genre almost. If you try to mix it, it goes tits up. You can’t do folk and house, or techno. Its probably why it didn’t ever get explored. But what it meant was people like James Yorkston, the Fence Collective, people like that would start playing it and opened people’s ears to musicians singing gentle beautiful songs maybe about love, maybe about death.

Four Tet’s Rounds is arguably the one record that modernised it.

Yes. You can guarantee those people bought The Wicker Man soundtrack. Fence – it’s their manor isn’t it? It was just the right side of finger-in-the-ear music, we wanted to stay away from there. That soundtrack has got a bawdy side and a sensual side too; it’s something very odd. The way that it’s influenced things is ridiculous and brilliant. It’s extraordinary. Thank God – it’s a great movie. I do wish we’d still got the rights to issue it. A lot of people tell me that the soundtrack issue was a definite kick up the arse for that film. It had a very slow speed spread into the consciousness. It kept getting poked. First it was Moviedrome, then the soundtrack.

Who have you met through it?

Anyone surviving who’s a major part of the story, I’ve met. Paul Giovanni died in 1990 (his New York Times obituary from the time failed to mention The Wicker Man amongst his achievements). He’s survived by a sister. She’s impossible to find. The trail for her went dead in Minneapolis. What I can’t believe is that she hasn’t seen any of the coverage. I had a phone number for her last known address and when I called a Mexican chap answered who had never heard of her. So I spoke to anyone I could… apart from Gary Carpenter because he genuinely hates me. I’m convinced of that. Every time it’s mentioned in the press, he does his rant about how it’s a bootleg. If I was a bootlegger, how did I end up in Pinewood with the bloody mastertapes? I did what I was legally allowed to do and no more – annoyingly! The thing was bootlegged to death, I remember going into a vintage shop on Laurence Corner near Euston and they had a box of them there on the counter. I asked where they came from and the bloke looked very sheepish. I’m pleased we did it and that I took the time to do it. It’s a great thing. It’s almost a confirmation that my taste isn’t actually that bad!

I love the fact that the story of the soundtrack is as interesting as the story of the film…

Like the film, it doesn’t really exist. There is no definitive version of it anywhere, just these things pieced together from bits that are out there. It’s more than likely the estate of Paul Giovanni threw it in the bin when he died.

Has anything else you’ve released taken that similar effort?

Not that would have that impact. It was almost like a gaping hole in the musical landscape that no one else had seen. I haven’t really seen any other gaping holes like that. There’s lots of little holes being plugged all the time by countless little labels. But there aren’t many gaps like The Wicker Man soundtrack.

Jonny still runs the always inspirational Trunk label releasing genius records, beautiful books and the occasional t-shirt that features a bonkers half-remembered sweet wrapper from the ’70s.