If you were walking near Tottenham Court Road underground in the late 1970’s – and if you were lucky – you may have heard a haunting, hypnotic sound reverberating through the tunnels and surrounding streets, merging with that peculiarly Soho scent: cigarette smoke, unsettled fresh beer, sweat, strong Italian coffee and the acrid residue of theatre-land air conditioning units pumping stale warm air into dark alleyways.

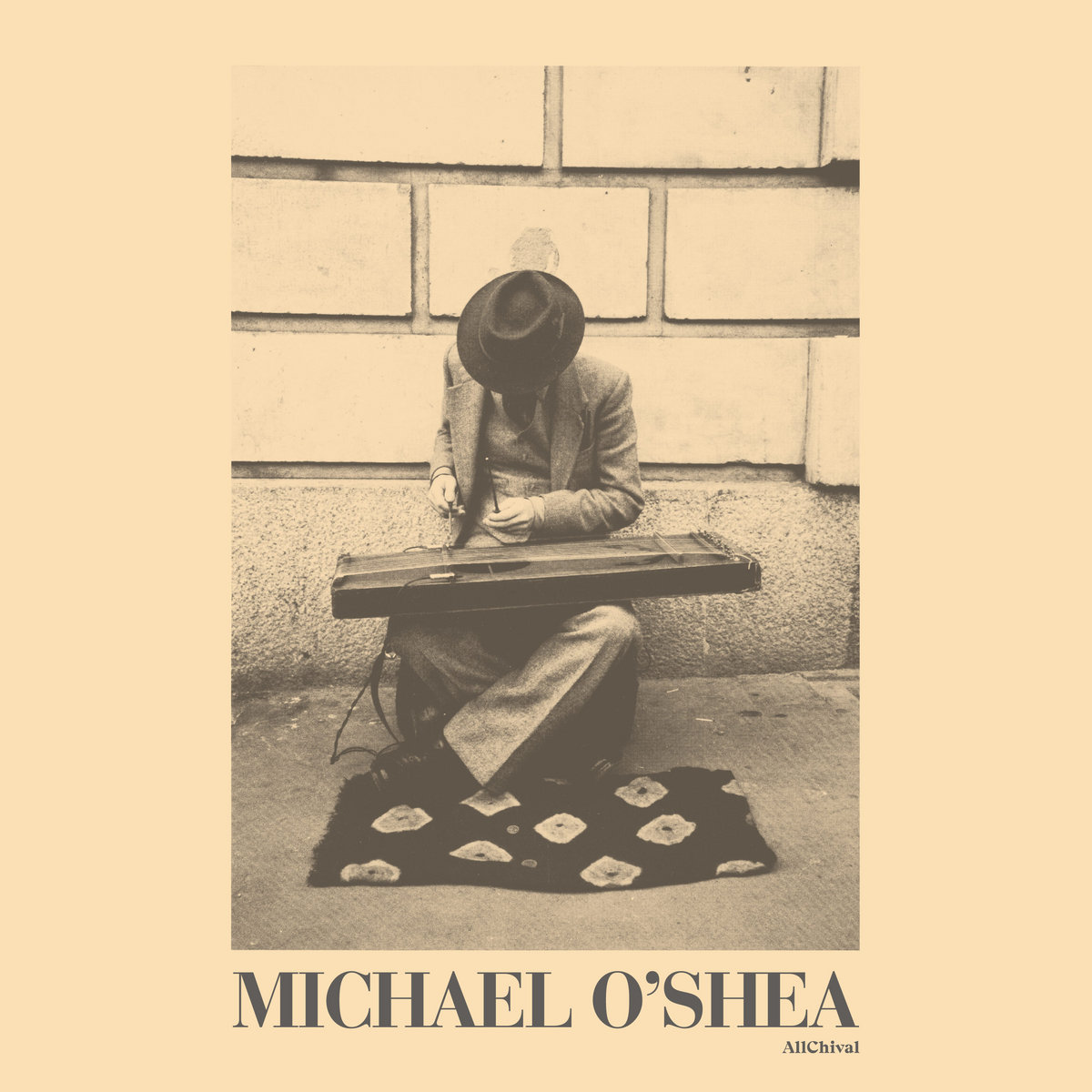

A true bohemian journeyman with striking features (missing front teeth, extravagant suits, turbans and dresses) eccentric ways and a generous spirit, the late Michael O’Shea was an original in every sense. Playing a hand-built instrument somewhere between sitar and dulcimer that he dubbed Mo Chara (‘my friend’ in Irish) – fashioned from part of an oak door salvaged from a skip in Germany – O’Shea drew influence from Bangladesh, Algeria, Turkey, India and Ireland. His was an idiosyncratic, beautiful sound: a dream music that evoked Medina shadows and Soho ghosts equally. Shane MacGowan once spoke of life as a dynamic dance of ‘cramming as much pleasure into life as you can, and railing against the pain that you suffer as a result. Or scream and rant with the pain and wait for it to be taken away with beautiful pleasure’. O’Shea’s music wasn’t about base pleasure or unutterable pain, but it was certainly about being taken away – it was flighty, a glowing will -o’-the-wisp on a dark night at the edge of marshland enticing you to dance into the dark.

Born in Northern Ireland in 1947, O’ Shea left home at 16, joined the British Army soon after, was stationed in Germany for a time, went AWOL and was jailed for a short period. Eventually travelling to Bangladesh in 1972 as part of a London group called Operation Omega – who supplied aid to the country during the war of independence – he was drawn to Bangladeshi culture, the music in particular. O’Shea eventually left the country after a debilitating bout of illness, returning to London with his beloved sitar in tow – an instrument he’d become seriously adept at.

Busking round Europe with it throughout the 1970’s, he met an Algerian musician in France – Kris Hosylan Harper – who played an intriguing handmade, bastardised Mellotron. Suitably inspired, O’Shea sold his sitar en route to Turkey, eventually pitching up in Munich where he salvaged the aforementioned door, building Mo Chara by stretching piano and guitar strings across a filed section of wood, securing the strings with pegs and adding a rudimentary pick-up, flanger and phaser. More often than not he’d strike the strings with paintbrushes, the brushes bouncing off the droning, echoing strings as he played. Refining his sound for a couple of years, he eventually added a second effects box – he called it the: ‘Black Hole Space Echo Box’ – arriving at a sound that hinged on fleet movement underpinned by warm, thrumming stasis; elegant tumbling notes supported by the almost dubwise echo of his effects unit.

O’Shea continued busking on his return to London, where he came to the attention of Ronnie Scott’s booker Will Sproule who – enthralled by the siren call of Mo Chara one morning outside Tottenham Court Road – booked O’Shea for regular opening slots at the club. His underground reputation grew – he opened for Ravi Shankar at the Royal Festival Hall and supported Alice Coltrane and Don Cherry – although he was, by all accounts, happier playing on the streets than in the clubs, disliking the routine and hullaballoo of the music business.

Bruce Gilbert and Graham Lewis of post punkers Wire used to drink at the White Lion pub in Covent Garden – then a dilapidated area full of artists, musicians, prostitutes, derelict lots and empty warehouse spaces – and were similarly enthralled by O’Shea, as remembered by Gilbert in Paul McDermott’s brilliant, sprawling oral history of O’ Shea published last year on Medium:

‘‘He was sitting on an amplifier, head bowed, crouched over what turned out to be a machine, a stringed machine, and this figure was wearing black court shoes, I think there were white stockings, a white pleated pencil skirt, a navy blue blazer with big gold buttons, a white turban and very large hooped earrings — and the figure didn’t look up. This person was producing this absolutely extraordinary noise. I went straight back to the pub to report to Bruce what I had seen. [Laughing] Of course he was questioning what it was that I had been smoking. I said, I think you had better come and have a look for yourself’’

Inviting him to record down at Black studio (they were mixing the Documents and Eyewitness compilation at the time), O’Shea turned up unannounced one morning in 1981 and – after a couple of false starts and a quick spliff – the mood was deemed right. He laid down what was to become his eponymous debut LP (originally released on Wire’s Dome Records, and distributed by Rough Trade, in 1982) in a single day. It was to be his only record.

Pivoting around the majestic ‘No Journey’s End’ – which plays out as something approaching a haunted jig, echoing strings conversing in sepulchral call and response – it also included ‘Kerry’ (whose sinister arpeggio evokes some long lost John Carpenter soundtrack) and ‘Voices’ – Mo Chara taking on a near choral intensity, a room filling sound. It’s a startling listen: it feels like O’Shea is both channeling – and distilling – a lifetime of travelling, of constant free motion; the lilt, movement and craw of a thousand discombobulated street scenes unfolding through the memory banks and into the notes.

His echo box effects – covering the mix in an aquiline, luminescent shimmer – adds to a sense of otherness. O’Shea’s music feels not alien, but slightly west of this world: familiar – through the folk traditions referenced, albeit at oblique angles – but just out of reach.

Indeed, his idiosyncratic sleeve notes added to the journeyman vibe: ‘Having had a somewhat chequered career to date, I will list some of the activities that have taken me thus, so far, along my journey: barman, waiter, soldier, labourer, packer, wireman, hippie, factory worker, salesman, hobo, manager, leather craftsman, odd job man, clerical worker, reconciliation relief worker, social worker, sculptor, designer, collector, joker, transvestite, inventor, psychonaut, actor, traveller, instrument maker…not wishing to dwell on my personal history I will leave you to imagine what I did in the gaps’

Like many, the first I heard of Michael O’Shea’s music was last summer when his album was re released by Allchival Records (it had been a long time favorite of Optimo’s JD Twitch, among a few others). In recent weeks, I’ve listened to little else. I’ve become quite obsessive in my listening habits, recently (it feels like certain sounds take hold of me and don’t let go, as discussed in a previous column) and O’Shea is transcendent in the truest sense of the word. His music facilitates cranial freedom at a time of physical constraint; the crawl pace routine we all inhabit – slate grey skies; near empty parks; paddling pools filled with brown rain water and leaves; Tesco aisles; the Co-Op where the cashiers shout of ‘the self service checkouts are free! The self service checkouts are now free!’ has taken on symbolic significance) – and speaks of a life we’ll know again, soon – away from the upside down, back to the out there.