Back in April last year I was on Dobbins Lane in ‘the village’ where I live when I chanced upon Will Burns out walking. I think he was coming back from the allotment which isn’t remarkable in itself except I hadn’t seen him in almost six weeks. We instinctively made space for each other, he walked in the road (it’s a quiet residential dead-end of a street) and neither of us properly stopped. You didn’t then, it was the early stages of the first lockdown and there was no chatting outside, didn’t want the local authorities spotting us. Never saw anyone on these brief walks so it was lovely but also pretty strange seeing Will there. As our paths crossed I said to him that he should write something for us for the site, not a poem though, something longer. Didn’t expect him to write a bloody book!

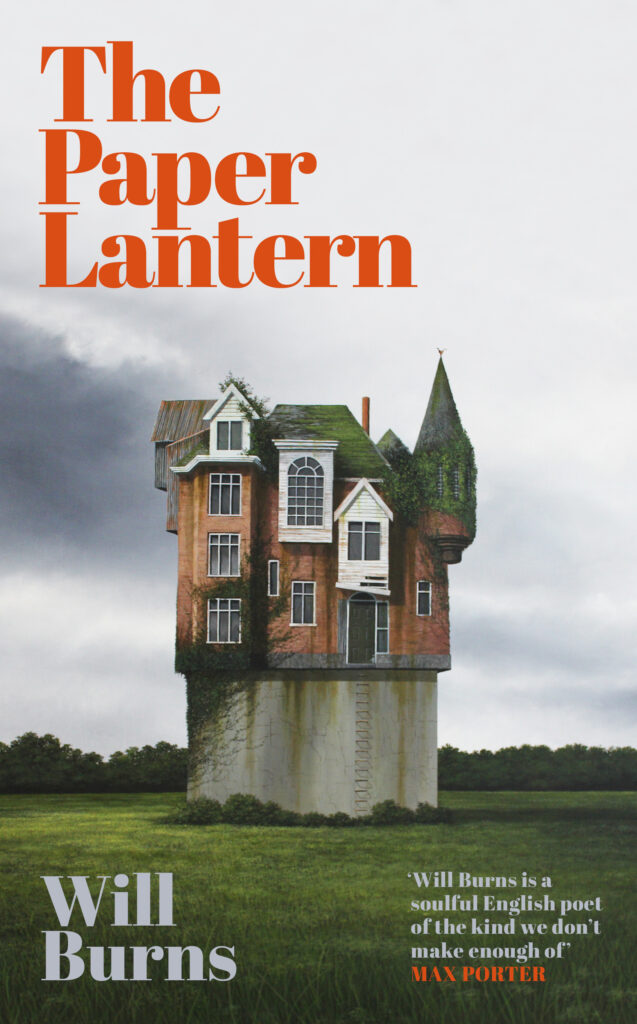

Will sent over his first post only a few days later called Where Do We Live Now?, almost as if he’d been sat on it already written, which in a sense I suppose he had for years. He sent another and another, thousands and thousands of words and it was obvious pretty quickly (whether he knew it or wanted it) that he was writing what has become The Paper Lantern – a remarkable novel we’ve seen brilliant pieces of in his poetry, vivid (and loud) glimpses of on pissed up nights down the pub in question. Or a pub very like it in any case! It was a total joy to witness it being written during that period when everything was a tripped out mess – going to the local shop was impossible for me to get my head round, let alone him writing so beautifully about the place we both live in. Anyway, it was great to read the Observer piece yesterday and to see the cover revealed today. We’re all over the moon for Will here.

Below is the post mentioned above, first posted in May 2020. It’s not an extract from the book but is, as Luke Turner just pointed out, part of its DNA and ours too at the Social Gathering.

Where Do We Live Now?

I.

We will begin with a rough physical description. The place is a small market town which, for some reason, insists upon being called a village. But how, you might ask, would a place insist on such a thing? Already we hit upon a point of interest—does the place have some innate sense of self? Or a voice to speak it? Some communal pretension that insists upon its own category? Perhaps we shall see. For now, it’s enough to know that the inhabitants call it a village and so, in the interests of conciliation, will we. Let’s return to the physical facts. The high street runs from east to west in a small incline up into the hills that surround ‘the village’. It is a high street of no real consequence, the same as any number across the country. A large coaching inn half way down, which is now a tired and yet expensive hotel. Three charity shops, a florist, a small Italian restaurant, a couple of curry houses (either excellent, depending on who you ask), four or five hairdressers, one of which is a large salon-type affair that offers all the usual other treatments—body hair, nails, facials. Across the top of Coombe Hill, which rises at the eastern edge of the village and has one of those delicious tautological place names, and down in the next valley is Chequers, the country residence of the Prime Minister. Please don’t think of this as a boast. You will, perhaps, learn that this is not the sort of thing to which I would attach any importance, much less crow about. Plenty in the village would though—and do. No, I mention this fact merely to add to our understanding of the sense the place has of itself. Its own status and specificity in the scheme of all other places.

We are eminent, the proximity of this great and historical residence says, though in our modest, suburban way. Close enough to London for the big players and the high rollers of the city to escape, but with all the trappings of The Country—monoculture arable farming, a Site of Special Scientific Interest (look at the adornment of capital letters…), lots of walkers and cyclists and their attendant synthetic fibres, bad pubs, good pubs, mediocre pubs and most importantly a school system which attracts a grasping, philistine middle class who propagate themselves on mutual congratulation and self-satisfaction. For some reason there are an extraordinarily high number of slightly secreted high-end restaurants. Sometimes it feels as if all people do in the area, having reproduced, is eat and drink and then talk about where they’ve eaten and what they’ve drunk. Fair enough, we might say to the people when we see them. What more should they have to do, after all? For my part life organises itself around the drinking, specifically in a pub called the Paper Lantern which is run by my parents. Or rather, it did, and it was, until a few weeks ago when, along with everything else in the country, the pub closed its doors until further notice while the virus was dealt with. In the time since the country closed-up-shop, I have, I am bound to admit here, indulged myself somewhat. I take walks that are longer than strictly necessary and find myself living a kind of dream-life. Of course it says something more again about this place that there has been almost no local news of any deaths, no regular facing up to the real, terrible impact of the disease. We heard early on that a man who had until last year owned one of the curry houses had died. But since selling up, the word was that he had moved away anyway. Other than that provincial rumour has been benevolent. News spreads here as anecdote, rather than through the rigour of research, as does what passes for objective reality. We are, after all, in the heart of Brexit-country, the safest Tory seat in the house, and just weeks ago, had you engaged in conversation with any one of a number of know-alls in the pubs you would have been presented with their second-hand opinions or dimly-recollected experiences of Europe and/or the EU as hard empirical evidence. I have no doubt there are people here who are secretly jubilant to find themselves in the current situation. A generation who have always struggled to define themselves against the terms of their parents’ totemic global conflicts finally have their own war. On the radio I hear about the disease’s capacity for exposing the fault lines of inequality and in the village I see the evidence of it in the disease’s absence. Here, there is a strange sense of the whole thing as a kind of long bank holiday.

I am implicated in this myself, of course—weeks without having to drag myself along to my dreary part-time job, days of walking, reading and writing. A listless, vague guilt. But at the same time, I find myself quite simply resenting the return of a life in which my worth is totted up at £8.50 an hour and comes with all that we previously held true, and about which I had, shall we say, ‘some doubts’, concerning work and money and status. Under what we must now call the ‘normal circumstances’, I work part-time in the Lantern and try to write my little poems, and am used to the odd looks people cannot stop themselves giving a thirty-nine year old man they find working in his parents’ pub. The hourly wage has long been old hat around here. The true currency is status. It manifests itself in a variety of ways. There are the obvious—the cars, the houses, the jobs. But there are many other playing fields, with none more vicious and competitive than the selective education system. In the pub, you hear the parents talking about private tuition, extra classes, past papers and maths coaches, desperate for their kids to pass the 11-plus and get to the local grammar school. Their faces have the strained, serious bearing that all the thirty-to-forty-somethings have in the village when they discuss the important issues of the day. Nutrition, the necessary pragmatism of their politics, the ecological considerations of their holiday destinations.

The lockdown, a word and an idea which has now, after weeks, attained the power of a brand, has coincided with a fine, sunny spring. We’d had a sodden winter and the relief is palpable that a bit of warm weather has arrived. Palpable how? Is the place itself giving voice again? With the pubs closed I no longer see my fellow residents every day, no longer exchange gossip and pleasantries and platitudes. Instead we see each other every now and then in the queue that forms in the morning outside the pharmacy and the little supermarket on the high street, or down at the allotments, or out walking in the hills. A brief hello and an ask after the family. Thank God for the sunshine… I have signed up to be available as help should it be needed in my ‘three-street zone’, and so I am sent a regular warden’s email with details of the local effort, successes, stress-points and a little motivational bluster. The emails all begin with some statement about the weather. I’m sure if I stretch for it, there is a clever point to be made about our relationship to the elemental things of the world, an opportunity now to achieve some older, or newer—lets not get bogged down in the deconstruction of Western conceptions of time just yet—but either way, a more fundamental, more ecstatic, knowledge of things. The poet-philosopher Tim Lilburn writes of the ‘mind deeply homesick and scheming return’. He is invoking paradise, the original garden, and a desire, an ‘eros’, we all feel for what has been lost in the Fall. A desire that manifests as a kind of homesickness. In turn, I suddenly see people noticing the songs and learning the names of local birds and plants, picking wild garlic in the woods and developing an interest in their gardens. The allotments look so well-tended and presentable they could have come out of a guide book.

I find myself, despite luxuriating in my lack of waged labour, and in a glut of what we once called leisure time, homesick for the pub, my own secular Eden. The week before he finally called for a closure of shops, bars and restaurants, the Prime Minister invoked ‘the inalienable right of free-born people of the United Kingdom to go to the pub’. The phrase is such a gory mess it’s not worth the time (despite the current abundance) to bother pulling it apart, and yet the primacy of his image is telling. Despite its ubiquity, despite its symbolic use by the tawdry politicians of the day and their cap-tugging cronies in the press, despite everything, the pub remains the locus of my current sense of lack. Our own is full of sad, amusing, strange and sometimes sinister types. I think of them now, after weeks of my own company, and appreciate their profoundly discrete selves. They resist the categorical. They are insistent on something like Lilburn’s ‘intensely felt differentiation’. Here is the hippie conspiracy theorist, half Midsomer Murders, half Monkey Wrench Gang with a box of his home-made pakoras for the anti-HS2 protest camp on the outskirts of the village, here is the seven-foot biker, white beard down to his belly button, here the improbably likeable misanthropic prison guard, the lost young man who works here full time, his head anachronistically full of banal bar-room opinion and pointless pub-quiz knowledge, here the quiche-and-pie lady, her name on a bottle at the bottom of the fridge, and who asks, conspiratorially, at the end of the night, for a large brandy to slip into her glass of white wine. Here is the woman with the glass eye, whose daughter played Tina Turner in the recent London musical, whose conversation every now and then betrays her frustrations at the more sinister aspects of home counties homogeneity. In simple terms there is a yearning for a return of some physical communal life, but beyond that, when I think of the pub, I think multitudinously. Of the possibility, if not the probability, of ecstasy. Lilburn writes ‘Perhaps individuality is not to be known, only to be lived with,’ and maybe that is why we find ourselves so at home in these rooms that are palpably not-home, with people we would never ask home, and who we would never want to go home with. Morning. I open the door onto South Street and take the white chalk path into the hills by the old wellhead again and walk and wait.

Will Burns

Artwork: Lee Madgwick

Preorder The Paper Lantern now