Reviewed By Martha Sprackland

‘all days have their inheritance’, the anxious narrator of little scratch muses. This particular day – the single, threaded day of Rebecca Watson’s debut novel – begins with a mild hangover, an almost-missed train, and proceeds through the mundanity of a day at the office. Soup for lunch, chitchat with anonymous colleagues, rote administrative tasks. The unnamed narrator dissociates, books lunches, visits the bathroom once, twice, three times, to kill the slow minutes, to scroll through Twitter and text messages, and to pick at – try not to pick at – the skin on her legs, a compulsion that her mind, strung across the pages of the book, returns to worry at again and again.

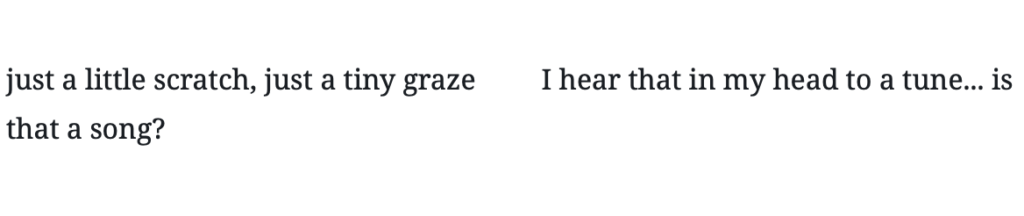

The energetic, modernist prose does sound like a song. Closer, like jazz. Words drift free of lines, thoughts disrupt and interrupt each other; sometimes two columns stand together on the page, the interior speech occurring simultaneously to an outward conversation, or a text message as it is read in real time, without pause. Words coalesce at the opening doors of a Tube train, words pedal their bike down a London street at commuting hour, words pile up on her phone (‘eighty messages in the group chat christ’). They swarm, glitchy, as the narrator’s mind returns again and again to pick at the scab that has formed over a wound she sometimes refuses to look at directly. It’s tempting to slow down, linger diligently over the words and shapes on the page, try and make sure you’re not missing anything, but that’s not in the spirit of it. Instead in reading I let my eye dash left and right and back, threading up to the top again, probably missing words in the miasma. The effect here is cumulative, osmotic, not linear, and I admire it. That said, perhaps I’m suitably primed for it – I’m a poetry editor for a day-job, and perhaps readers less accommodating to the formal experimentation and white-space play of concrete poetry would find it less to their taste for that reason. The reception it has received suggests this is not the case.

Watson skillfully induces a panic and itch, a sympathetic anxiety that draws the reader into the world of the book. A lesser writer might’ve tried to keep the source of this wound back, to turn the novel into a whodunnit, a mystery to be unfolded. Watson is bolder than this. From early enough in the book we know exactly what has been done; we know exactly who has done it.

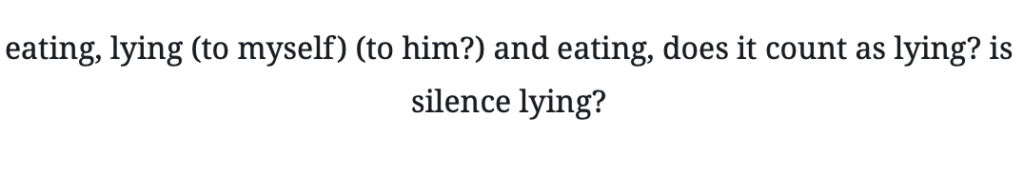

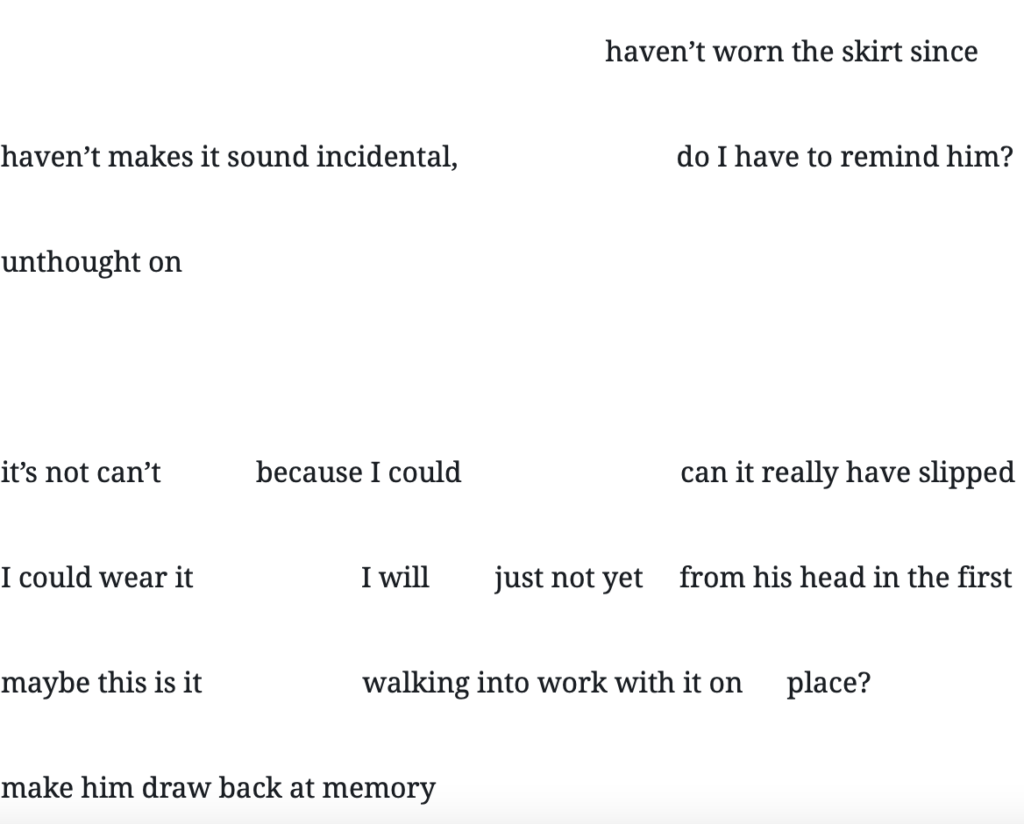

Standing counter to the bullying, enforced presence of the rapist is the beloved ‘him’, the protagonist’s boyfriend, who, though appearing in the flesh only towards the end of the novel (it’s a work day, busy enough that they manage only a few texts back and forth) runs through it like a golden thread, the fact of him a comfort and also a possibility: if she can bring herself to confide in him, ‘my him’, to expose the scab to the air and light, then she might begin to heal. He represents both the welcome possibility for redemption, and still, in the difficulty of it, the representation of all that is whole and inviolable. She feels shame, both in the fact of it and the secret of it:

and on top of this, a meta-shame at the shame she knows she should not feel (‘I was raped but at least I wasn’t killed!’). The abuser’s silence, too, is interrogated, as he interacts with her blithely, brusquely, apparently without acknowledgement of what he has done. She is perplexed, incredulous:

But she isn’t helpless. She toys with the potentiality of memory, that she could – by pushing at his memory (we don’t truly believe, of course, that he can have forgotten), forcing him to confront it, confronting him herself – bring to mind the damage, bring into his mind that which is polluting her own. She enacts small moments of her own violence, using a special tool to punch the day’s papers onto a spike in the newsroom, like a butcher-bird; peeling a banana ferociously (‘breaking its neck pulling down its clothes’). The inward-turning voyeurism of the novel itself feels carefully worked. Every page is marked by her fury, powerful and incandescent, beneath the veneer of docility that office life demands.

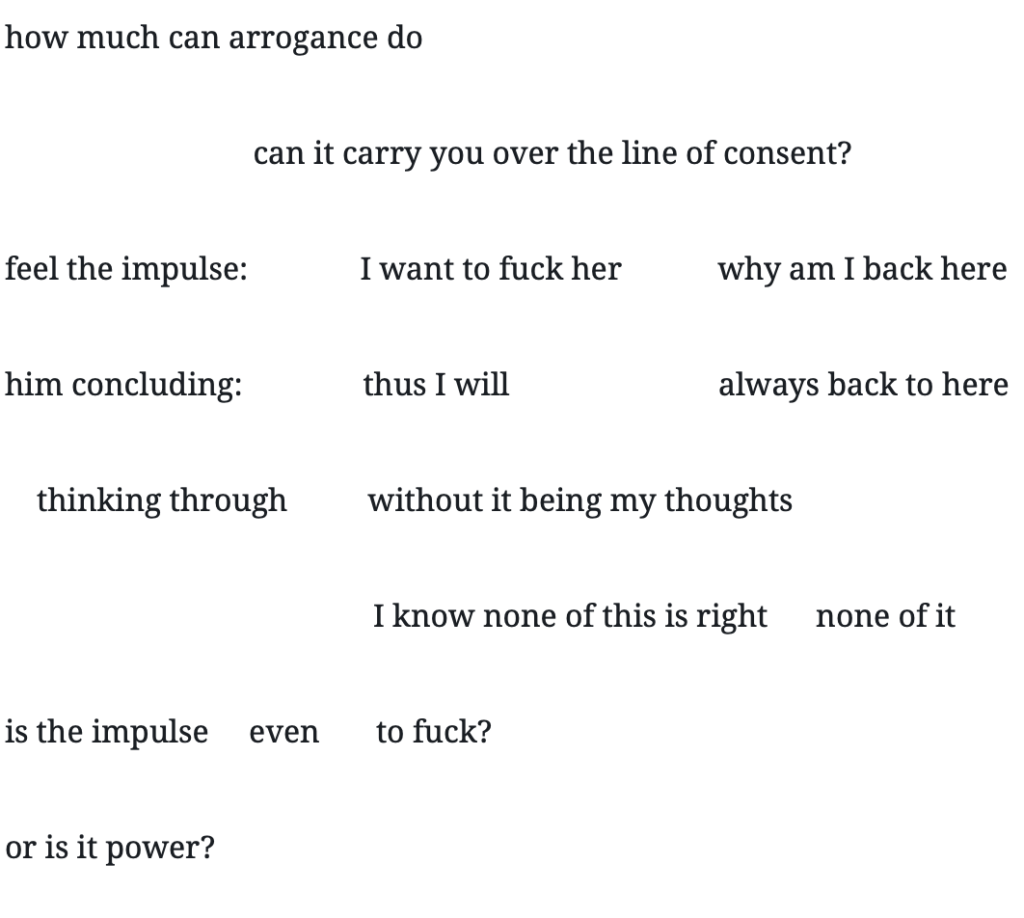

little scratch is defiant, often a fuck-you to the entitlement of the abuser, the process by which another person can dare to enact, assimilate, justify or utilise harm:

She picks at the surface of motive as she picks at her own skin, won’t leave it alone, whilst simultaneously determinedly continuing with her own life; worrying about her writing (which has stalled), thinking about sex (which she is triumphant in wanting, despite everything), loving her ‘him’, scrolling the internet, biking to the pub, texting her mum (who, like her boyfriend, is oblivious).

For the narrator, there is very little silence. There are two realities here in helix – the world of the office and the working day, the train, the pub, and the inner, often repressed world of the narrator’s thoughts – and where one pauses for the breath the other fills the gap. It tells and tells and tells. These are fragments that form the whole, that form a day in the life, and in its very multiplicity it shows how recovery might begin.

This short, simmering novel is audacious, interrogating agency and obsession with acuity and empathy. It’s a brutal read, magnificently cacophonous, the reverberations of which linger long after the final page.

Martha Sprackland

Order little scratch from our friends at the LRB Bookshop here