We Are I.E. was one of the first records to signal a shift away from the European and American music that had dominated the raves of the late 80s. With its Amen break, reggae bassline and gunshots it laid the groundwork for a style that would become uniquely British and eventually develop into what would become jungle…

Lennie De Ice: Growing up I was into the new wave of hip hop and electro like Mantronix, Jonzun Crew and Afrika Bambaataa, plus I’d grown up in the era of Gary Numan, the new romantics and ska, so I had been blessed to have those eclectic styles of music around me. I used to go into the local music shop on my way home from school and play around on the drum machines. They would let me stay in there and mess about until closing time. I was fascinated with these little boxes that you could make beats out of.

In 1986 I got my first keyboard which was a Juno 106 and my first drum machine was a Roland 505. I was also DJing around that time and I’d warm up for people like Linden C and Dez Parkes playing rare groove and hip hop. I was part of a sound system with my friend ET, who I would later make jungle tunes with, and we would use the drum machine to make sounds effects and little jingles for ourselves. Around ‘87 I was introduced to acid house when I went to a rave on Carpenters Road in East London. After that, I went to Sunrise, Energy and Metamorphosis. I remember hearing A Guy Called Gerald at Dungeons on Lea Bridge Road in East London and thinking to myself ‘yeah, this is on!’ It gave me goosebumps. I started playing for a promotion called Empathy which was mainly at The Dungeons and we also did Astoria and Milk Bar. Me and my mate that had shown me how to use the drum machine would perform live at the illegal raves as Ill Tempo. We had the keyboards and sequencer on stage, I think we might’ve been doing that before Guru Josh and Adamski. In 1989 in we did a PA at The Dungeons and Adamski was there and started playing along with our set. It was going off and I wanted to replicate the excitement of the rave and capture that feeling in a tune.

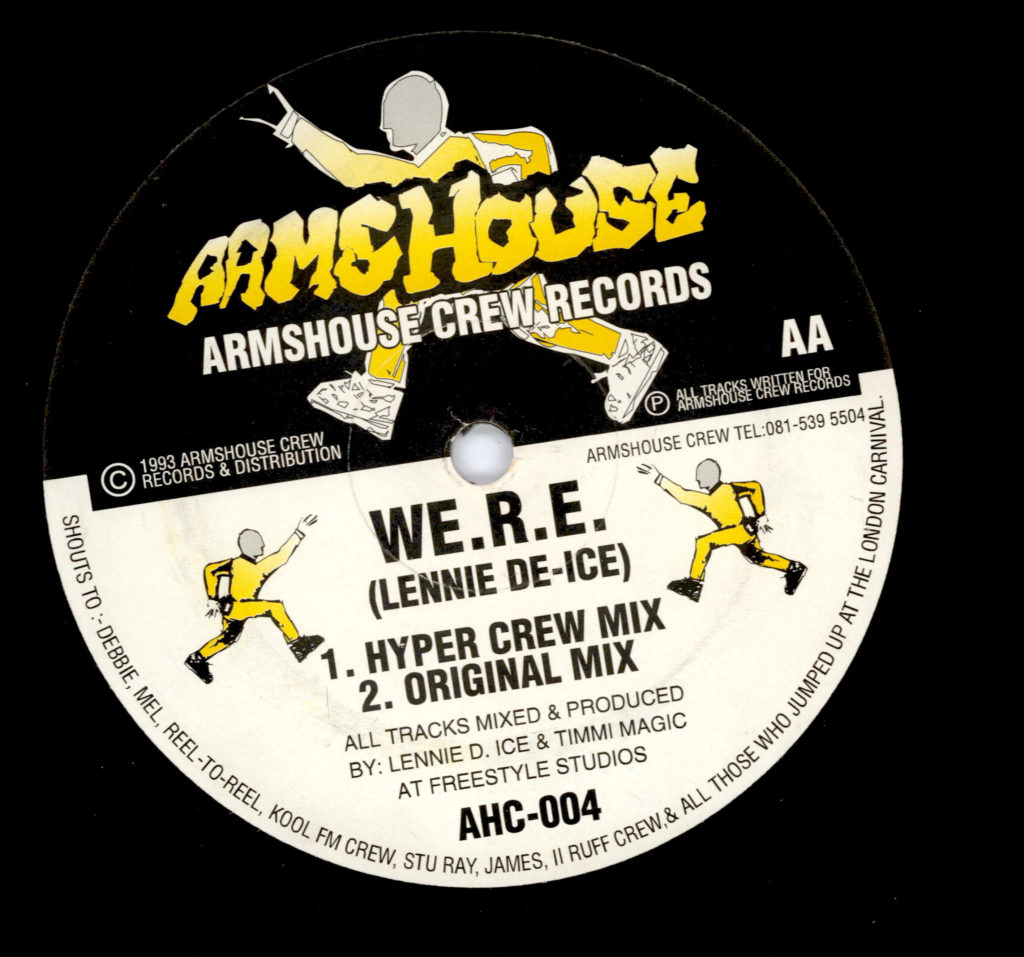

I had already set out the beats for We Are I.E. in December ‘88, but it was done at 118 bpm. I took the Amen break off King Of The Beats by Mantronix and then it was just a matter of finding the rest of the samples. I found the spinback and the gunshot off a Simon Harris sample compilation. It wasn’t common to have a gunshot on a dance record back then, but I was coming from the sound systems where they would use it as a sound effect. I found the “we are e” sample, and it was part of a whole chant. I’d been building up my studio equipment, so I had a reel to reel, a sampler and an Atari which cost about £800, and it only went up to 4MB! Uncle 22 showed me how to use Cubase on the Atari and I met up with Coolhand Flex’s brother Long John [John Aymer] who ran Reel 2 Reel and his other brother Michael ran the De Underground record shop. Randall, Uncle 22, Flex and A-Sides were part of their crew so I would play them my stuff. I was playing John some tunes, and We Are I.E. was probably about the 15th one I played. He thought that one was the winner. He wanted We Are I.E. and another track.

We used to go and see Paul Ibiza and Potential Bad Boy from Ibiza Records as they had a studio and had been around for a while. John played it to them and they thought it was very advanced and didn’t know if people would take to it. It was a hybrid tune, I didn’t really know what I was making. I wanted to make a tune that symbolised everything I was into – the breakbeat was hip hop, the gunshot and rewind from the sound systems and the 4/4 from acid house. John decided to put it on an EP with tunes by Uncle 22 and Coolhand Flex. The label was going to be IE Records and We Are I.E. would be the one to launch it.

We got a dubplate cut at Music House and there was a big rave that night called Living Dream at Eastway Cycle track in Leyton. Randall was playing there and he loved the tune. He had dubplates of the whole EP, which no one had heard before. I remember his set and while I was standing by watching what was happening, he told me he was going to drop my tune. We Are I.E. came on, and there must have been at least six thousand people in there but I could only see the first couple of thousand and it looked like they were dancing to it, but slowly. I wasn’t sure if they understood it or if they liked it and wondered if John had picked the wrong track. Then Randall said he was going to play it again at the end of his set. When he played it the second time, I could see more movement than before. They were familiar with it and liked it. The people at the front were having it and as I walked further back, the crowd was into it.

Around the time it was released I went away for something that happened about 4 or 5 years prior which had caught up with me. It sounds crazy but the whole time the tune was being played out the only way I got to hear it was on Kiss FM or on the pirates because I was locked up on F-Wing in Brixton. At night-time when all the screws had gone, people would put the radios on and have a little rave inside their cell with some puff or whatever drugs they had; trips were rife inside. I was locked up at the same time as a few of the rave promoters from back in the day and a lot of the people inside had been ravers. I remember Colin Faver playing it one Saturday night; people knew it was my tune and they all had the plastic cups banging against the bars in the cells when it came on. It was sad but a proud moment at the same time. It’s a shame I never got to see the full impact that the tune was having apart from that night at Living Dream. I came out of prison at the start of ‘93. Reel 2 Reel had been taking care of the record and sold about 16,000 copies out of the boot of the car. It took me a long time to make but I did it exactly how it was supposed to be done and it resonated with people. I felt like we were a musical family on a mission, an example of the future. It still gets played in old school raves and on the UK Garage circuit, but I never had an ego about how big the record was as the people around me kept me grounded. To be considered one of the pioneers for the template of jungle is an honour.

Lennie De Ice

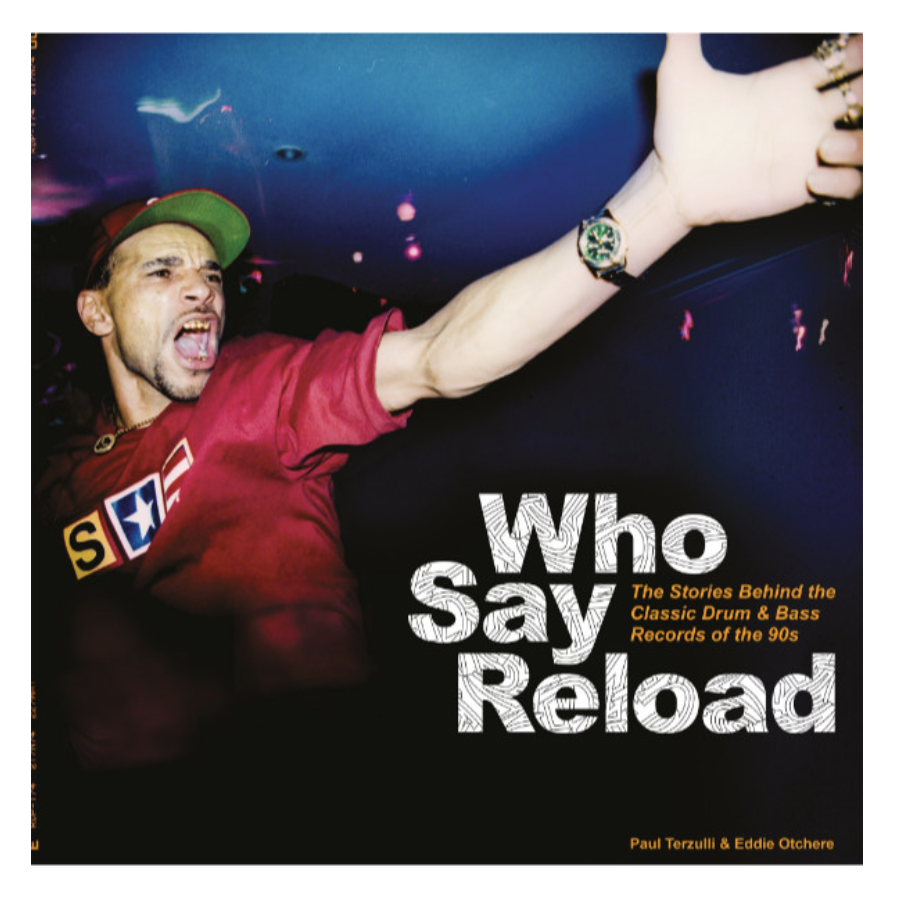

Order ‘Who Say Reload’ here through Velocity Press