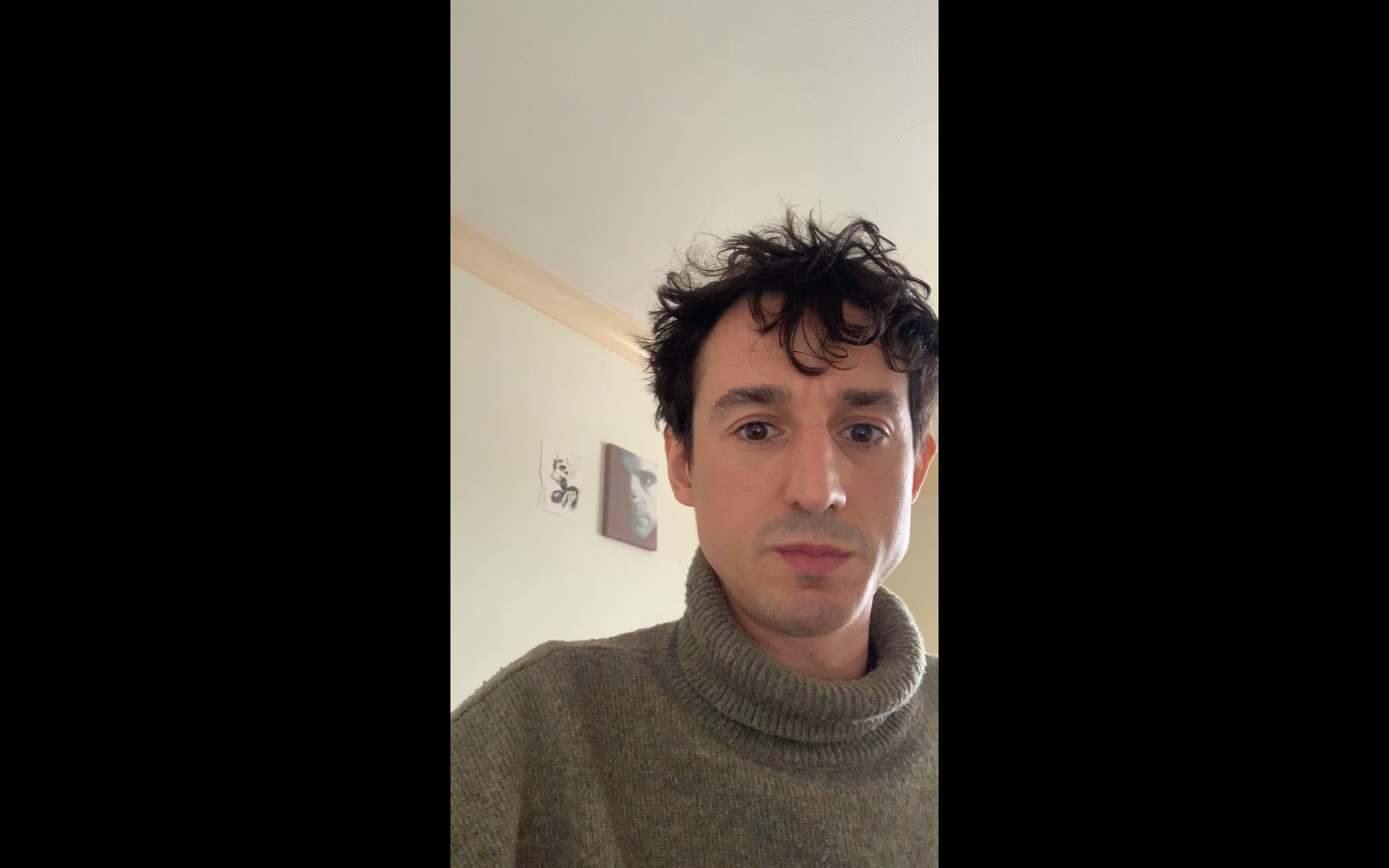

As part of our on going ‘We Are One’ week we’re pleased to share this special broadcast from Lias Saoudi with you.

Lias’ posts for us have been a hugely important part of The Social Gathering, he’s been with us since the first week (a year ago) and contributed some truly brilliant writing. Big thank you to him for this series. Long may it continue.

Am I unwell? I think I got a whiff while I was waiting in line to buy filters in Sainsbury’s the other day. Clasping two choux buns and a bottle of red wine I started reading the greetings cards. The one that broke my heart had a picture of a chimpanzee on the front, with a caption that said something like ‘you can’t help growing old, but growing up is optional’. Visits to the supermarket have left me vulnerable to random bouts of depression during the pandemic. That omnipotent male voice on the intercom in co-op assuring you over and over again that we’re all in this together, the dislocated choir of self-service check outs busily de-constructing your will to live as you weigh up your wares, the fathomless insult of the instore radio; pop hits of the recent past about passion, late night lust, summer vibes and spontaneous joy that didn’t make any sense the first time around, now about as uplifting as the sound of someone drilling the last few screws into your coffin before burying you alive. It’s in the supermarket – especially those of the inner city with their tight galley’s – where one gets the most acute sense of having finally arrived in a Paul Verhoven movie, where one has no choice but to quietly admit to themselves as they fondle the avocado’s that the great game might well be up.

Given a year of these conditions, I can now chart an exact correlation –undisturbed by alternative stimuli – between how much I feel like hanging myself and how much time I spend on social media. I’m also acutely aware that when my other addictive tendencies flare up, if I’ve been boozing or drugging, up shoots the scrolling in tandem. I have begun muting people I’m positive I’m actually quite fond of. Pity, jealousy, fear, loneliness and resentment; these are what too frequently await me when I type my passcode into my phone, yet I persist, after all there’s nowhere else to go, right? I’ve begun letting go of the idea that this pandemic is something we will get over, a bump in the road, after which it will basically be the 1920’s again – until the collapse of the bio-sphere at least. As my psychic resilience has started to crack, my thoughts at times have become nothing short of poisonous. It’s begun occurring to me just how naïve I’ve been. Some sort of threshold has been crossed in this period, a process that began truly heating up just over a decade ago is baring its hideous crop.

I’m not sure I’ll ever recover from reading Rosin Kiberd’s The Disconnect – which was published earlier this month. Her book felt a bit like the lights coming on at the end of a lengthy night out, one where you’ve been holding on in spite of yourself, in spite of the fact you hate the music, the drugs are no longer really working and your sexual prospects are null and void, suddenly you can see all these deformed, deranged faces…one of them is your own. Born in 1990 she charts a personal history of the web, from the innocuity of its cumbersome early years right through to the techno-dystopia of today – watched over by our inverted Promethean overlords. A panoramic of our current malaise then. She has the kind of critical mind that seems to be able to unearth a labyrinth of meaning in the least suspecting places; whether she’s exploring the Tamagothci, the night gym or Monster Energy drinks. Like Mark Fisher before her, the more personal things become the more crucial the prose. By splitting open her own soul, by bravely baring the wounds born of this hideous new communication dread-scape, we are at once terrified yet suddenly less alone.

What struck perhaps the strongest chord with me were Rosin’s short essays about dating. In particular a hook up which lead Rosin into a fever of anxiety regarding how her potential partner might – because of an interview she’d recently conducted with an un-named, perhaps slightly controversial polemicist – confuse her as somehow politically repulsive, as insufficiently woke. How our online selves – performatively good – these impossible avatars, self-congratulatory and cold, have infected the world we actually inhabit, robbing us of a chance at actual connection is at the core of this book. She charts a solemn, guilt laden drift away from online politics in the wake of mental collapse, deciding she has nothing to offer but futility, misanthropy and despair; describes her attempting to keep up to speed as only conducive to further feelings of uselessness. It’s chilling to think of minds like hers locking themselves off from any kind of debate about changing the world, given it seems to be on fire.

I’ve always thought of myself as a misanthrope, but the overwhelming feeling I have nowadays when I observe other members of my species at close quarters is of a crippling kind of pity. It’s the little bit of effort people insist on making: a nice outfit, an elaborate ring tone, an excited bit of dialogue in the park about their kids or their kitchen extensions; the contempt with which I’ve long held my fellow travellers suddenly reveals itself to me to be nothing more than a protective veneer, a shroud of indifference I’ve been using to ward off of accepting how chronically sad all of it actually is. I’m one of these animals. As hopelessly self-absorbed and lost as the rest, probably more so. I spend my days embroiled in a bitter, soundless culture war, furious diatribes and counter diatribes popping off left right and centre in the middle of my skull, unbornsoliloquys of the deep void pertaining to nothing but paranoia, malformed class loathing, hypocrisy and rejection; in my head there has seldom been less peace, I am forever screaming at nothing in my head.

Lias Saoudi