We were surrounded by streets of tenements. They were constructed like impregnable medieval forts in a rectangular shape. Our block consisted of four streets: Springburn Road at the top, Palermo Street and Vulcan Street directly opposite each other and Ayr Street at the bottom.

Each tenement consisted of three storeys. There was a space outside the flats which was known as ‘the back’ where the dustbins were kept in the middens. The little brick washhouses where the women used to wash clothes had been boarded up by the time I was born. If you got inside these buildings you would find rusted metal antique mangles with huge winding handles to wring wet clothes on. There were filthy, cracked sinks too. These were foreboding, forbidden places and we hardly ever dared enter. Dead spaces with strange energy; spirits of the past were trapped there. As a kid I could feel unseen forces in abandoned places.

There was a brick wall that ran the length of the street which divided Flemington Street from us, with a lane that could be accessed from Ayr Street. The ground was all black dirt with cracked and broken paving stones which would be used in fights with a few scattered gangs in rival streets. There was no grass to be seen anywhere, and washing lines full of drying laundry held up by big wooden poles traversed the backs in every street. On a sunny day, women from the upper flats would hang their washing out on V-shaped poles from their back windows. The kids would shout up to their ma for a piece and sugar, two slices of white bread spread with butter or margarine coated in sugar. That kept you going on those long summer days in the 1960s.

The flats were accessed by ‘the close’, an open doorway at street level which led into a hallway that went straight through the building into the back. The doors to each flat were on the left and right side of the close and the stairs to the upper levels were broken by a small landing between each floor with an outside toilet.

*

Springburn was a really vibrant place. I remember the men coming back from work at teatime and the kids hanging outside the pub at the top of the street waiting for the dads to come out, because the men would get back knackered and go for a quick drink and a blather with their mates before going home, when the wives would have their tea cooked and ready for them. There’d be men selling the evening Times newspaper, or the pink on a Saturday, which had the football results. I vividly remember coming home from visiting my grandparents in London Road, Bridgton with Mum and Graham and seeing the newspaper vendor on Springburn Road outside the pub at the top of our street selling the pink with the headline IBROX DISASTER – 66 RANGERS FANS CRUSHED TO DEATH. Celtic were winning by one goal to nil in the Old Firm derby and the Rangers fans having given up hope were leaving in droves. Then, in the very last minute of the game, Rangers centre-forward Colin Stein equalised, and those leaving heard a huge roar from inside and tried to get back into the stadium, causing the flimsy metal safety barriers to collapse. Sixty-six people were tragically crushed to death. It had an effect on me, a feeling of dissociation (although I wouldn’t have known how to describe that feeling at that age). Boys at my school would have been at the match with their dads. Death was real and close, and not just something that happened to bad guys in the movies.

The Aberfan mining disaster had happened a few years earlier; a whole school full of kids the same age as me crushed to death underneath a mountain of coal from the pit nearby. It had been all over the news. This tragedy entered my childhood imagination in a big way. Sometimes when I looked out the classroom window of my school, which was overlooked by a big hill on Hyde Park, I would wonder if a similar thing was going to happen to us.

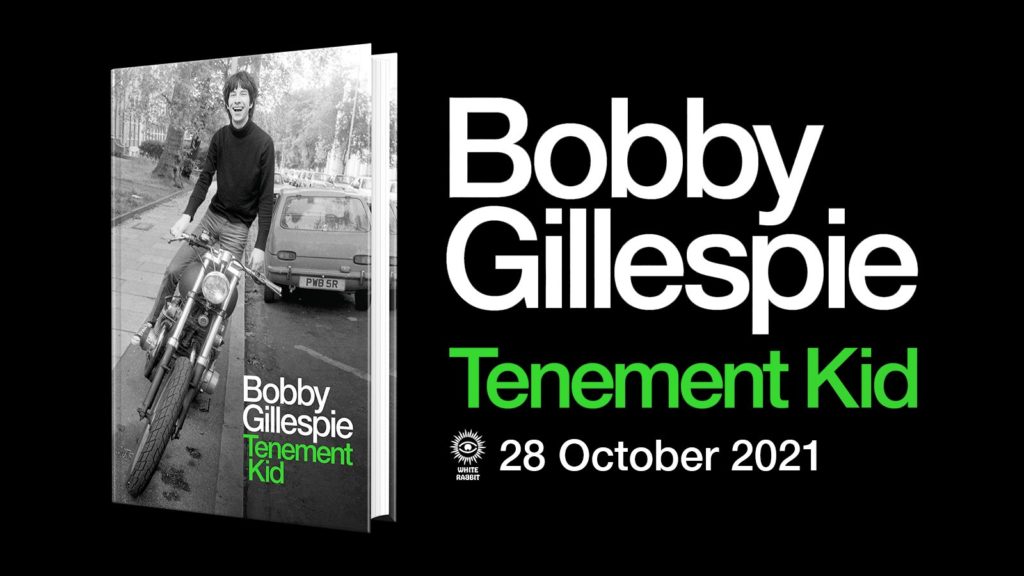

Bobby Gillespie