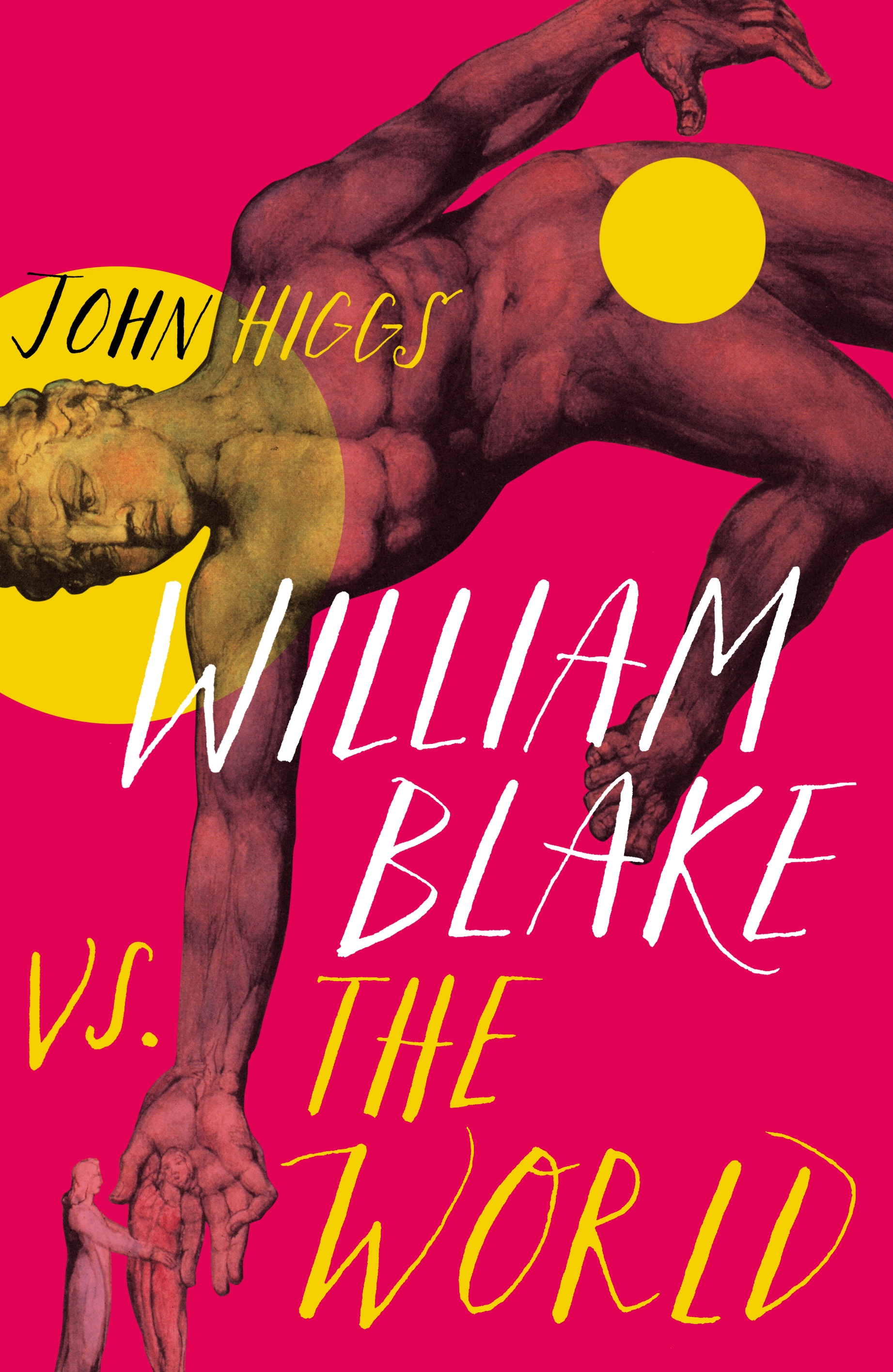

Wild, mercurial, uncategorisable – three words that could be applied to both William Blake and the author of a radical new biography of the poet, artist and visionary who has inspired and baffled for generations. John Higgs takes us on an unexpected journey through culture, science, philosophy and religion to better understand William Blake in the twenty-first century, and we are delighted to share this extract.

On 28 November 2019 – William Blake’s 262nd birthday – and for four nights afterwards, Blake’s final painting of Urizen was projected onto the dome of St Paul’s Cathedral in London. Urizen is a central figure in Blake’s personally mythology, a stern bearded patriarch who represents the limits of rational thought. Bedridden Blake finished tinting this image only days before his death, and it had now become the defining image of the major retrospective exhibition then running at Tate Britain. It hung at the end of the show, presented as the inspired climax of Blake’s life’s work. It had been used for the exhibition poster and was an unavoidable image in London tube stations for many months that year. The idea of projecting it onto the dome of St Paul’s was a scheme to further promote the exhibition. For admirers of William Blake, this felt like a vindication. Blake had hoped that his designs would become large scale public artworks, even though it never looked possible in his lifetime. There are not many artists who critics dismiss as an ‘unfortunate lunatic’, and who end their days in an unmarked pauper’s grave, who go on to have their work used to crown the great temple of Britain two centuries later.

Organising the projection was, by all accounts, a logistical headache. Permission was needed from everyone from the air traffic authorities to the emergency services, but the result was worth all the bureaucracy. Urizen’s long hair and white beard, which Blake drew blown dramatically to the side, were animated so that they rippled in the fierce winds of the formless unseen void beyond our world. Squatting, naked and muscular, he leant out of the spiritual sun of the imagination and reached down with an open golden compass in his hand to construct the limited rational world that we live in. From a viewing position on the London Millennium Footbridge across the Thames, the top of the compass merged with the pointed roof of the south transept of the cathedral. It looked as if Urizen was creating this great church, both the physical building and the religion that it represents.

With his long white patriarch’s beard, it is easy to mistake Urizen for God, especially when he is pictured in the act of creating the world. Urizen, in Blake’s mythology, made this same mistake himself. But Urizen is not God, no matter how much he may look like Him in that image, and no matter how much he deludes himself into thinking he is. Urizen is, in Blake’s words, ‘the mistaken Demon of heaven’ or, as he states simply in Milton, ‘Satan is Urizen’. Blake insisted that Satan/Urizen was a necessary part of all of us, of course, something that we should understand and learn from rather than deny. It was Urizen who divided and abstracted chaos to build our models of the world, the past and the future and our sense of ourselves. Yet he was still Satanic or demonic, due to his deluded sense of self-importance, his belief in the soulless, material world he created, and his refusal to acknowledge the true spiritual sun that gave birth to him. He was not what you’d expect St Paul’s Cathedral to celebrate.

For those familiar with the symbolism of Blake’s mythology, it was difficult to believe this was actually happening. If anyone had approached the officials of St Paul’s to ask if they could project an image of Satan on to the dome, they surely would have said no. Why they agreed in this instance is unclear. It is possible that they did not understand Blake’s mythology, and that Blake’s current reputation or the general god-like appearance of Urizen were enough to convince them. The alternative is that they fully understood the implications of branding a cathedral with Urizen and, in a moment of clarity, agreed that it made complete sense.There is now a long tradition of Blake being celebrated by authorities in ways that were, to those who understand his work, fantastically inappropriate. When the Labour and Conservative parties sing ‘Jerusalem’ at their party political conferences, they are presumably unfamiliar with the context of those words in the preface to the poem Milton. As they heartily bellow the lyric, moved by the stirring music, they seem unaware that they are calling for the revolutionary overthrowing of the ‘ignorant Hirelings’ of ‘the Camp, the Court, & the University.’. The song is sung by schoolboys in places such as Eton College who seem not to know that they are the uninspired, insipid targets of Blake’s words. Blake is trying to persuade them to take up mental weapons, such as ‘Arrows of desire’, as well as physical ones, such as the sword that shall not ‘sleep in my hand,’ in order to burn their college down.

Then there is the 12-foot-tall metal statue of Newton, created by the sculptor Eduardo Paolozzi in 1995, which is based on Blake’s painting of the same subject. Blake showed the great scientist as an avatar of Urizen, focused on a pair of compasses marking a circle on paper and oblivious to the immense wild world beyond his limited logic. That wild world is absent in Paolozzi’s statue, yet it is still an impressive statue which is only funny because of where it is sited. It was placed on a high plinth in the courtyard outside that great establishment dedicated to book learning, the British Library. That the image is intended to mock the limitations of this form of knowledge is as clear an illustration of Urizen’s blinkered nature that you can get. It is also another example of the establishment not just failing to understand Blake, but getting him so wrong that it is hard not to suspect a trickster spirit is somehow at play. To misunderstand something and place it in an unfortunately ironic context can easily happen once, but when it seems to happen every time, it does make you wonder.

These misunderstandings show a clear gulf between Blake’s worldview and that of the powers that be. On one level, it should not be surprising. His work is deep and rich and no matter who looks into it, they will always find their own prejudices and interests reflected back. Perhaps he is too big a mind for us to ever properly grasp, and we are doomed to always fail. Perhaps the best we can do is find our own version of Blake, and take pleasure in knowing how incomplete it will appear to others.

We owe it to Blake, though, to at least attempt to get the basics right. Blake’s understanding of the world was profoundly different from not just his contemporaries, but from western philosophy in general. It is a perspective which, if grasped, offers us a vision of ourselves, our country, and the wider world which would utterly transform our future. How wonderful it would be to have Blake commemorated in large public works which not only impress, but which are understood.

John Higgs

WILLIAM BLAKE VS THE WORLD will be published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson on 1 June 2021 – PREORDER HERE! John Higgs will be joined by Salena Godden, Kae Tempest, Robin Ince and Neil Gaiman on 27 May to discuss the appeal of Blake in the twenty-first century.

Tickets are available here through the British Library