My sister, Anna, messaged me on Monday morning (22nd March) telling me that the musician Dan Sartain died over the weekend. He was 39 years old.

The news shocked and saddened me. Since his first full album, Dan Sartain Vs. the Serpientes was released in 2005, I have been a fan of Sartain’s brand of rockabilly garage rock. I even used to cover some of his songs when I’d play at friends’ house parties during the same era.

Dan Sartain was a native of Center Point, Alabama. He was part of the scene around Swami Records—home to bands such as Rocket From the Crypt, and John Peel favourites Hot Snakes—and later signed to One Little Independent Records (Björk, Cody Chestnutt).

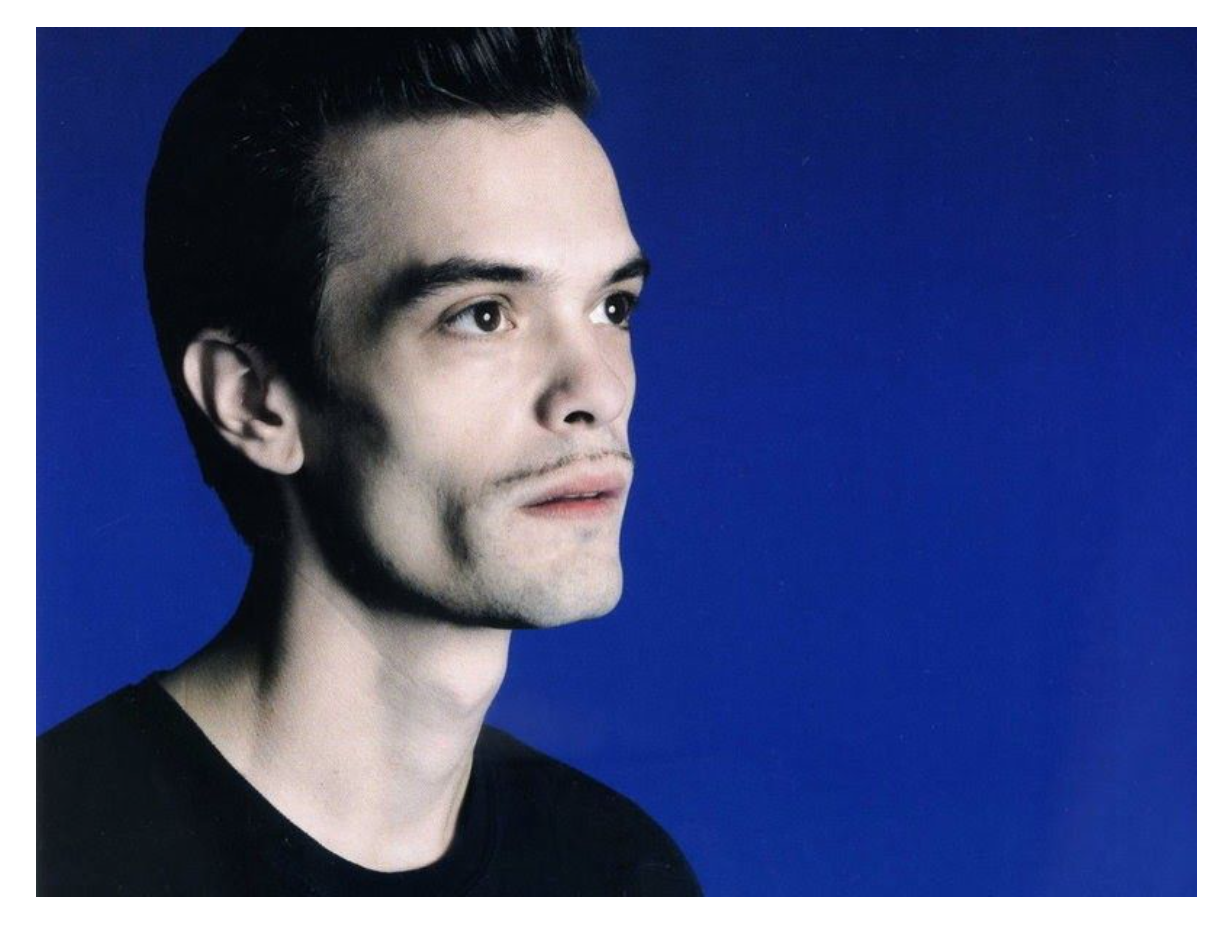

Sartain cut a distinctive figure in the mid-2000s rock scene. He looked like something from the 1950s biker gang B-movies that inspired the weird world of exotica that he conjured in his songs. He wove the ominous imagery of serpents and cobras throughout his albums.

There was a darkness to his lyrics and to his album cover artwork, but also a sharp wit and a playful imagination behind those ideas.

There was a moment, after the release of his second album in 2006, when it felt like Dan Sartain was destined for the Big Time. In 2007, the White Stripes hand-picked him to open for them on their Icky Thump tour. But for some reason, he never found the wider audience that his talent and originality deserved.

I met Dan Sartain just once. It was in 2010, in Bethnal Green, at an all-dayer that I was playing with my then-band, My Tiger My Timing. The venue was a kind of coffee shop mixed with a market that had a stage at one end of the room. As we wandered around the market stalls before our set, we bumped into a man who resembled a younger, more rakish version of the cult film director John Waters. It took me a beat to realise who it was.

Dan Sartain.

He was standing next to a record stall for One Little Indian (as they were then known). I blurted out how much I loved his music and that I used to play covers of his songs. Dan was generous in return—being a Southern Gentlemen, I believe it’s called in the States. He told us that he was playing later that same day, but in the meantime, he’d been asked to tend the stall for his label. Without warning, he handed me a whole stack of his records along with some Björk and Sugarcubes LPs from the merch boxes. When I asked if he was sure that this was okay, he winked and replied, ‘I’m the only cock in the henhouse.’

During our set, Dan stood right at the front of the stage. My Tiger My Timing was a Balearic-inspired synth-pop band, named after an Arthur Russell song, but on that afternoon in East London, we were doing a stripped-down acoustic set, and our drummer, Gary, was just playing percussion. Behind us on the stage, there was a drum-kit set up for another band’s performance later that day. Every couple of songs, Dan (who may have been somewhat inebriated) would step forward and ask whether we wanted him to ‘sit-in’ on drums. Each time, we politely declined. I’m not quite sure how this would have worked, as I’m fairly certain Dan Sartain had never heard of our band before, let alone heard any of our songs.

After our set, and before Dan took to the stage, certain members of our group (who shall, for the sake of their carefully airbrushed reputations, remain nameless) joined Dan around the back of the venue to smoke a particularly potent strain of weed that he had been partaking of all day. Perhaps we offered to ‘sit-in’ for him during his solo set. I don’t recall. The rest of the evening is pretty hazy from there. I do remember that we exchanged phone numbers.

I stayed in touch with Dan Sartain during the decade since. We’d message each other two or three times a year, usually just to shoot the breeze. Sometimes he’d send me recordings of new songs he was working on. Mostly we’d talk about music, and send each other new discoveries and recommendations. Recently, he was enthusing about the eighties LA punk band, X. He’d also share the oddball home movies of his adventures around Weird America, including The James Dean Memorial Junction—a surreal and ghostly tribute to his hero, who famously died in a car crash at the age of 24.

In recent years, Dan got married and started a family back in Birmingham, Alabama. In 2018, he opened his own barbershop there. The interior was truly a sight to behold. The kitsch 1950s-style barbershop reflected his idiosyncratic tastes and personality. But the decision to open this new venture also showed how hard it is for musicians to make a living out of their music in this era, even for those with an engaged international audience.

The last time I messaged Dan, I told him that I was sorry to hear he didn’t have a label for his new collection of songs. He seemed positive in spite of the setback, signing off by saying, ‘I’m doing ok! Don’t worry bout Dan!’

RIP Dan Sartain. I hope they give you the atheist funeral you always wanted. You will be missed, mi amigo.