There is – Phil Collins aside – something gloriously deranged about the very idea of the singing drummer. It’s the combination of physical chops – flailing limbs, strained larynx – in contrast with the steadying pulse, the yin yang of rock n’ roll brought into sharp focus: untethered chaos tempered by ruthless discipline. And John Garner of early 1970’s proto metal flayers Sir Lord Baltimore was, without question, the ultimate singing drummer, the driving force behind one of the most demented albums of the 1970’s – Kingdom Come.

Charging out of Brooklyn with a full throttle fuzz attack that hinged on Garner’s orgiastic, near canine vocal delivery – a mad, yelping, leatherbound bray – alongside Louis Dambra’s frantic, animalistic leads, here was sweltering New York summer made vivid sonic flesh. It evoked crumbling brownstones, bottles of Thunderbird, slowly melting Quaaludes; an early 1970’s mind palace of pimps and dealers, ranting street prophets, bitter Vietnam vets, steel barricaded liquor stores – transportation music, essentially.

Recently, like many, I’ve craved vivid escapism. For six weeks at the end of the summer it was a very specific trinity– mid period Thin Lizzy, George MacDonald Fraser’s ‘bawdy’ Flashman novels and the slow, beautifully boring, mid 1970’s episodes of Van Der Valk that did it. I read, watched and listened to little else – a strange feedback loop, repeated daily. Flashman swilling brandy and dodging bullets in mid-nineteenth century malarial fleshpots; Phil Lynott singing tales of Irish mythology and Western folklore against Brian Robertson and Scott Gorham’s mystic, somehow palpably ancient, leads; Barry Foster skulking the grey streets and murky canals of Amsterdam in a brown leather jacket and black polo neck, staring out of windows, answering the phone by muttering ‘yes?’, pouring himself a freezing cold Oude Jenever and looking for low level gangsters with names like ‘Pater Heinrichs’, ‘Nick Schloss’ or ‘Johan Brandenbreiss’. It started to manifest as a peculiar drone: a self-imposed netherworld to negate the visceral brain-mash of 2020. The interiors of Van Der Valk, in particular – sheer 1970’s Europorn – are addictively soothing: the nicotine stained brown bars where everyone drinks halves of Amstel, froth lopped off by a little plastic scraper, the glass coffee tables, brown and orange wallpaper, tantalising glimpses of seventies Paradiso flyers (CAN, The Edgar Broughton Band, Hawkwind, Sun Ra).

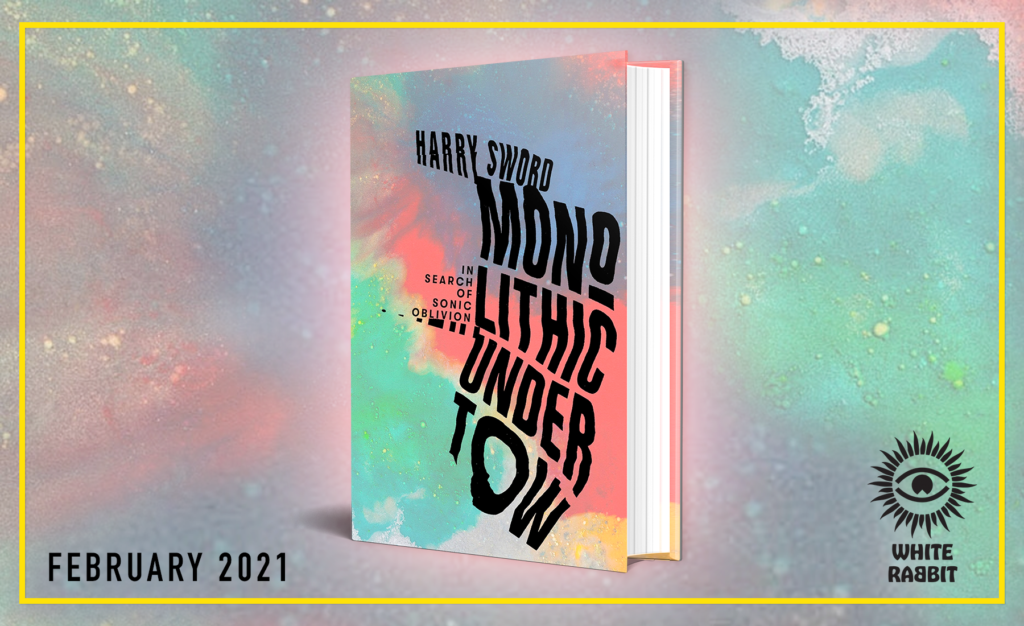

Into the second month this self-imposed parallel universe began to constrict, however. It was Sir Lord Baltimore who provided the requisite cosmic kick that – finally – broke the trinity. I’ve long been fascinated with what has, in the past decade or so, come to be loosely termed ‘proto metal’ and touch on it in Monolithic Undertow.

Put briefly, we’re talking obscure early 1970’s bands who shared a Sabbathian heviosity, outsider vibe, downer lyrical bent and, crucially, built songs around fuzzy, droning, repetitious riffs rather than big choruses and obvious hooks. Lyrically themes of war, madness, drugs and delirium were common. Ultimately this was the music of the circle – the riff vamping hypnotically in glorious swirling motion.

Some bands – Sir Lord Baltimore, Budgie, Trapeze or Bang, say – are (in underground terms) relatively well known. Many more remain obscure. Some cadged brief major label deals and proper studio time. Most operated deep underground, self-releasing long forgotten 7”s and touring crumbling Midlands pubs or, in America, seedy rustbelt dive bars. Recently, labels like Riding Easy, Rise Above Relics and Numero Group have done sterling work tracking down, archiving and re-releasing troves of long lost lo-fi nuggets. Riding Easy are already on volume 11 of their superlative Brown Acid compilations, trawling the length and breadth of the US for cranky proto metal gear, Numero Group released the fascinating, self mythologising Warfaring Stranger: Darkscorch Canticles (going so far as designing note perfect logos for long forgotten bands and a special D&D esq. roleplaying game) while ex Cathedral vocalist Lee Dorrian – a long term proto – metal champion – runs Rise Above Relics (the re-release arm of Rise Above Records), putting out beautifully researched archival releases. Personally speaking, this sound represents a vivid personal wormhole away from the churning fuckpiggery and devilment of end game capitalism.

Crank it up and think of the following as escape portals…

Stonewall – Stonewall (1975)

Total grail. Like many, I first came across this through the enthusiastic name checking of Endless Boogie’s Paul Major. Stonewall are shrouded in mystery but the story goes something like this: recorded in 1972 by a bunch of Long Island session musicians it was released, without their blessing, as a tax break by a ‘label’ (in name only) called Tiger Lilley in 1975. The band, of course, never received a penny. Based around the oily, roiling groove of lead guitarist Bob Dimonte, Stonewall was recorded in an inebriated haze in a Little Italy basement and simply hums with the mystic underbelly of NYC: you can practically smell the unrisen pizza dough and sticky black hash. Original pressings go for well over £500 but Kismet re- released it a few years back. Essential.

Josefus – Dead Man (1970)

Coming out of the humid mid 1970’s Houston backstreets, Josefus were purveyors of the greasiest, droniest, sleaziest low slung vibes imaginable. Garnering a dedicated live following in Texas but (way) too dirty and detuned for FM radio, Dead Man was their second LP and songs like ‘Crazy Man’ and ‘I need a Woman’ was glorious unabashed proto doom; swampy beyond belief. Check their spectacularly sinister version of ‘Gimme Shelter’ – all oil slicked heat haze, and superior to the Stones original.

Barnabus – Beginning to Unwind (1973)

A special record, this. Languished in total obscurity until it was recently unearthed and re-released by Lee Dorrian. Barnabus – a West Midlands power trio – had serious proto metal credentials having once won a Melody Maker ‘battle of the bands’ judged by Ozzy Osbourne and Geezer Butler. Beginning to Unwind is a monolithic slab of raw, bluesy, doom inflected gear imbued with a folksy edge courtesy of ‘fourth member’ Les Bates, who provided the wonderfully dunderheaded, basic, sixth form protest poetry esq. lyrics. ‘The War Drags On’ covers a similar beat to Sabbath in full ‘folly of war’ mode – an intense slab of dronal, downbeat slurry – while ‘Gas Rise’ was inspired by the pollution kicked out by the Ford factory in Leamington Spa. It’s pure 70’s dread: you can taste the stale Watney’s Red Barrell and feel the sickly heat of the two- bar electric fire on your face as you fall asleep in a haze to the BBC test card.

Randy Holden – Population II (1969)

Sheer proto doom, Randy Holden played for a while in Blue Cheer but Population II surpassed even them in rusty cave-man sonics. Holden was something of a primitive virtuoso, having played – from an early age – cranky surf guitar worshipping at the altar of Dick Dale and Duane Eddy, before joining Blue Cheer in the late sixties and contributing to New! Improved! (1969). Known for his ludicrously maximal volume fetish, he rigged up sixteen vast 200 – watt Sunn amps for Population II. The resulting album was a dirgier, dronier affair than the Cheer, hinging on Holden’s masterful command of space. Inspired by the drone and clang of both natural world and industrial machinery – at one point during recording Holden became worryingly obsessed with the sound of a ceiling fan – Population II is just dreadnaught heavy, a total downer power trip.

Bang – Mother/Bow to the King (1972)

Featuring some of the most brilliant/preposterous cover art of all time (the band sitting round a table, done up in capes, being served a freshly baked flat bread by the eponymous ‘Mother’), Mother/Bow to the King was the Philidelphia bands second record. One of the harder bands of the early 1970’s they were terminal stoner Sabbath obsessives whose debut album – Death of a Country – was rejected by Capital Records as it encompassed a half hour song ruminating on terminal American decline, it was deemed potential commercial suicide, and didn’t see the light of day until Rise Above issued it in 2004. Mother was recorded during the same sessions and rolls along hypnotically, hitting a sweet spot somewhere between dirgy Sabbath (check ‘Humble’ – it wouldn’t have sounded out of place on Paranoid) and folksier fare with the occasional funky detour (‘Keep On’ sounds like Sabbath doing a porn soundtrack. It is, obviously, the finest tune on the album).

Harry Sword

Order Harry Sword’s ‘Monolithic Undertow’ here!