Let me begin by saying that I envy people their gods. I envy their ghosts, their unseen guides, their visions and shivers of intuition. Not unrelatedly, I also envy people’s transgression and transcendence, their states of expansive wildness. Ekstasis — the experience of being outside of oneself — comes in many forms; its absence or impossibility can be felt in many ways. Sometimes I covet the peace that seems to accompany faith. Other times I think I would like to roll on the floor and babble in tongues.

As a novelist, it’s less the object of belief that I seek, and more the imaginative possibility of belief itself. For one whose life is supposed to revolve around the conjuring of lives and landscapes that don’t exist, an inadequate relationship with the unseen feels like a particularly acute failing.

This frustration at materiality’s limits manifests most pressingly in the form of novels I’m unable to write. Periodically, when I’m alone and quiet, I seem to glimpse in some distant region of my mind the insubstantial outline of a novel that not only can’t be described, but can’t even be directly imagined. They are like faint stars, these half-ideas: bright at the edge of my eye, enveloped by darkness when I face them head on.

The problem, of course, is that in order to write something you at some point have to give it form, and it is precisely through form that the ineffable is diminished. In seeking to catch in language and imagery the essence of an idea, we often supplant the idea entirely, creating in its place something easier to grasp, but stripped of the mystery that moved us. Just look at the history of God: an all knowing, all-pervasive, un-gendered energy, collapsed into the body of a bearded man.

As I came to the end of my second novel, Perfidious Albion, this feeling of being trapped by what I could comfortably conceptualise reached a new level of intensity. Albion was a work overly in thrall to phenomena I could already see in the world around me; its aftermath was a feeling of being suffocated by surfaces. I had written myself, it seemed to me, into the corner of a small and stifling room, over-stuffed with bulky furniture, none of which was mine and none of which I seemed able to remove. And all the while, as always, that other novel would hover just out of my eyeline — formless, insubstantial, mocking.

My newest novel, Come Join Our Disease, is not, I must say at this point, that novel. It constitutes neither a radical break with form and language, nor a successful harnessing of whatever strange and subterranean instinct gives life to the spectre of the un-captured novel inside me. It is, instead, a novel about someone whose frustration with the superficial, the pre-conceived, the routine, becomes a kind of trauma, and who enacts in response a radical break of her own: from society, from the bounds of acceptability, and ultimately from the world itself.

When we first meet Maya, the novel’s narrator, she is homeless. Seized from the encampment on which she lives, she is offered a chance at regular life. A tech company will sponsor her, provide her with clothes, a job, a place to live. In return, she must engage in a strenuous programme of wellness, and document on Instagram her glowing transformation into a healthy and productive member of society. Quickly, though, her ability to abide by the programme’s limits unravels, and she begins to rebel. Finding in the emergent space of transgression more freedom, more life, than in the world of daily drudgery, she embraces an ethos of transcendental degradation, finding through bodily and emotional decay a spiritual release at once exhilarating and destructive.

To imagine this journey on Maya’s behalf, and indeed to try and imagine myself making that journey with her, was to become more intimately aware of my own limitations than ever. The feeling of working in a cramped and confined space, hemmed in by objects and artefacts, was thankfully gone, but in place of frustration was a feeling of fear. If I, dully hamstrung by the quotidian as I so often feel myself to be, was to have any hope of making this journey alongside her, it seemed obvious to me that I would need a guide, a source of inspiration, perhaps even a protector.

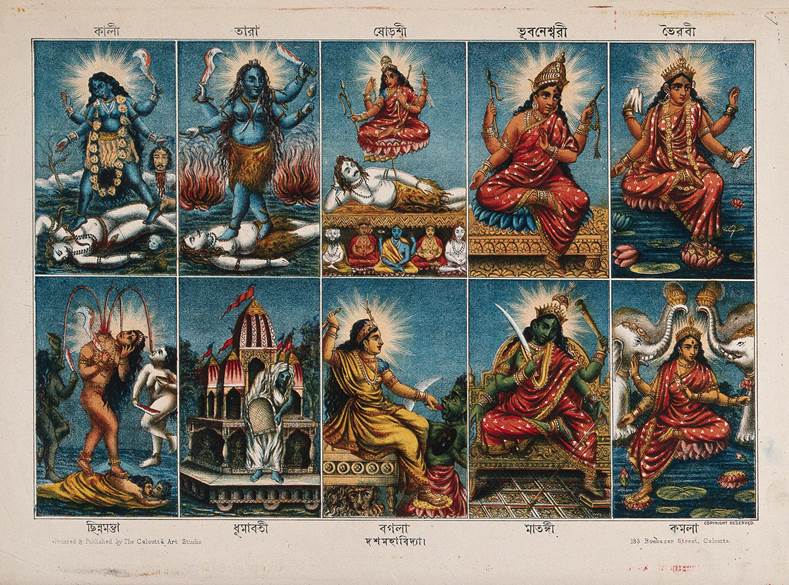

The cultural history of empowerment and enlightenment through the radical acceptance of life’s most feared and uncomfortable aspects is rich and widespread. The Aztec belief system, for example, held space for Tlazōlteōtl — the excrement-eating goddess of filth, sexually transmitted diseases, adultery, sex work and vice. In India, one can still encounter members of the Aghori — ascetics mistakenly stigmatised as cannibals — whose worship of Shiva inspires them to live at the edges of charnel grounds, half naked and smeared with funeral ash. Indeed, the Tantric tradition in general is suffused with the symbology of death’s cosmic significance. The ten goddesses collectively known as the Mahavidyas include Chinnamasta, who is depicted removing her own head, sometimes while copulating with a corpse, and spraying from the stump of her neck a fountain of blood which nourishes not only her own severed skull, but her two devotees, making her all at once the sacrificer, the sacrifice itself, and the recipient of the sacrifice’s power.

From India, this lineage of holy transgression, which so subversively dismantles our assumptions about the sacred, the virtuous, the holy, and of course the feminine, makes its way to Tibet, and it was to the unique imagery of Tibetan Vajrayana Buddhism that I found myself most drawn. Through the Bardo Thodol, better known to us in the West as the Tibetan Book of the Dead, I experienced vicariously the lonely, profoundly moving post-death journey, during which we vacate the world of form as experienced via our bodies, and enter instead an inner landscape, populated first by the more benign deities of the pantheon, and finally by a host of flesh-eating, blood-drinking furies.

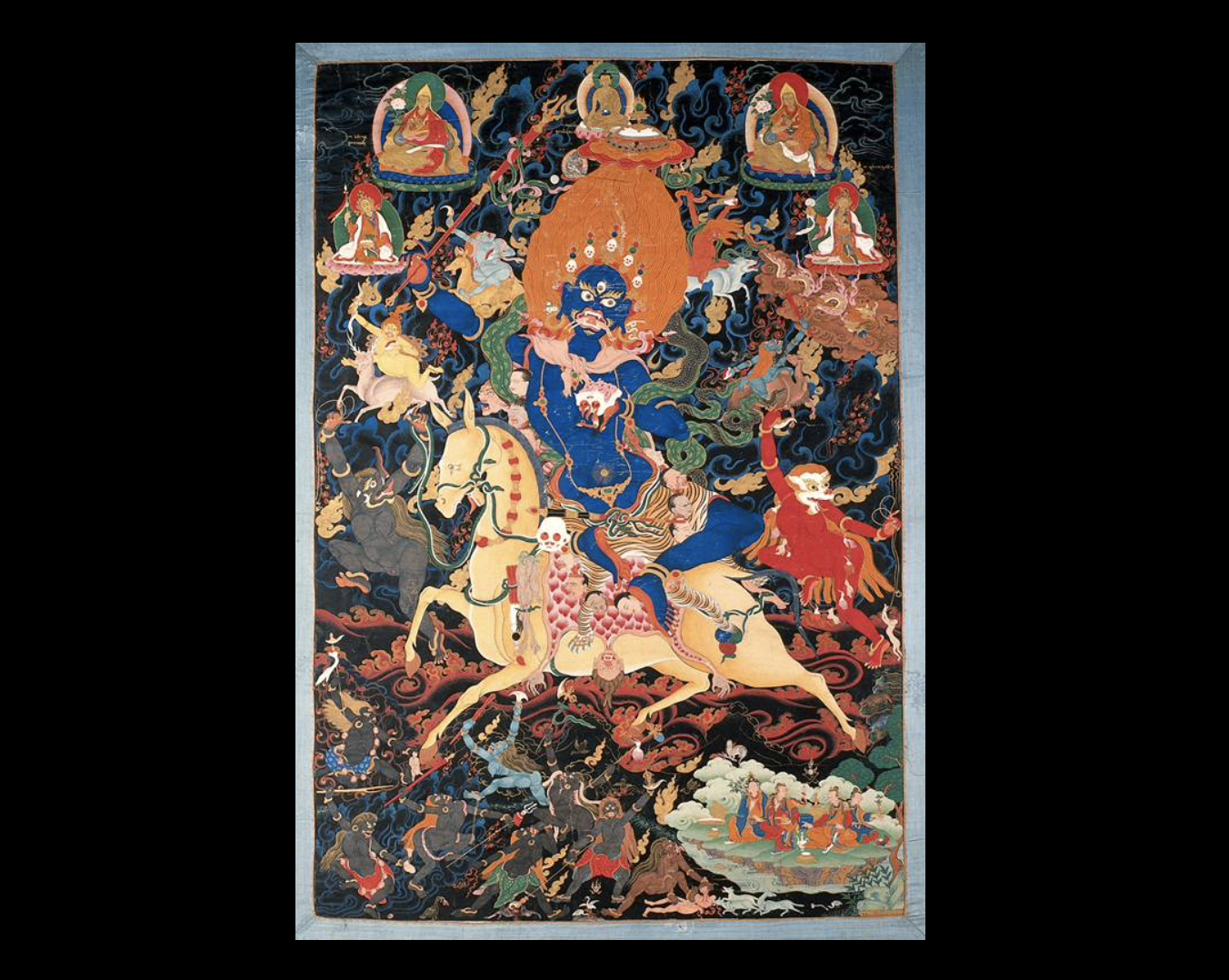

It was by this route, as I sought out images of these beings I could only in the loosest sense conceptualise, that I came across a painting that condensed into a single, snarling, three-eyed visage not only all the forces, histories, traditions, and instincts I was trying to parse, but all the inner blocks and expressive obstacles I was trying to overcome: the wrathful mother herself, Palden Lhamo.

Palden Lhamo, or Shri Devi, to give her her Sanskrit name, is a Tibetan protector deity, likely an emanation of Kali. Depicted most often as a terrifying, emaciated crone, her leathery skin appears blue-black, but is in fact chameleonic, shimmering between hues depending on her moods and activities. Perched side-saddle on a possessed mule, she emerges from a black tornado and rides across a roiling cosmic ocean of blood and fat. In her left hand she holds a skull cup, filled with blood and liquefied entrails; around her neck are strung the severed heads of demons and ghosts she has pacified. From the reins of her mule hangs a flesh bag filled with all the diseases and plagues of the world. The mule’s saddle, on which Palden Lhamo triumphantly sits, is made from the flayed skin of her only child.

It is unusual and indeed uncomfortable for me to describe in prose a personal experience without refracting what I feel through the lens of fiction. Perhaps I fear that what happens to my ideas will happen to my feelings: I will give them shape and a name, and their new-found form will diminish them. For a long time, my experience of Palden Lhamo was much like her image: at once compelling and intimidating, inviting inspection yet bearing a glare that demanded caution. I became obsessed with her. Every morning before writing I looked at her; each night before sleeping I called her to mind in the hope she’d appear in my dreams. I felt as if she were speaking to me directly, forcefully, and yet I couldn’t translate what she said into something I could say myself. It was only later, with something approaching relief, that I read China Galland’s description of her own first encounter with Tantric imagery, and saw in its words precisely what I’d failed to name:

‘I was shocked, most of all, because I recognised these images, they were familiar, though I didn’t know from where. Seeing them was like the experience of finding words for feelings that I had long held but had never been able to express . . . They broke through and knocked down the false images I had had of myself. They stripped me of the veneer of nicety . . . [They] were like mirrors, reflecting back anything I had been afraid of in myself.’

Our reaction to these images can be visceral. We can feel affronted, repulsed. But the apparent violence they depict is a code for something we struggle to approach and accept directly: a compassion so heightened, so urgent, that it manifests as wrath.

The intention both of these images and the beings they take as their subject is not to harm us but to shock us, forcefully, from the harm we unthinkingly inhabit. Corpses and skulls symbolise not victory in a physical battle, but triumph over our true enemy: the ego. Entrails and blood are not a celebration of brutality, but an expression of the freedom that accompanies the dissolution of the body. The flayed skin of Palden Lhamo’s child symbolises not cannibalism or sadistic punishment, but the difficulty, the pain, and ultimately the liberation, of severing our material attachment — even, and perhaps especially, our attachment to what we love the most.

In the mirror of Palden Lhamo, I saw what constrained me, what held me back, what I feared. I saw also my timidity, my very human instinct to resolve what felt self-limiting not through any determined destruction of pre-conceived ideas, but through the endless reshuffling of those self-same concepts. Most of all, though, I saw what held me back, what I couldn’t relinquish, and I saw it not in Palden Lhamo’s fierce gaze or slavering jaws, but in her saddle, the flayed skin of her son, which I understood in an instant, without needing to consider it any further, to represent all my previous work.

As writers in a reified age, we are encouraged to be attached to our books, as if the books themselves, rather than the processes and experiences that led us to write them, are what matter. In many ways, books are our response to, and futile defiance of, death. We read them to exit the grip of time, to enter a liminal, suspended space in which neither our body nor the world around us seems to age. We write them because we hope that, long after we’ve rotted, they might outlast us. For months or even years after a book is completed, the writer drags its carcass around with them, taking it to this or that event, reanimating it in this or that interview, revelling in its illusory ongoingness, its false substantiality, its reassuring actuality. Our very biography becomes books — the ones we’ve written, the social media archive of the ones we’ve read. But in celebrating the written word we all too often calcify it, and obscure for ourselves a fundamental truth: that every book is a cadaver, a decaying idea. At the moment they come alive for the people who read them, they die for the people who write them. If they didn’t, nothing new could flourish.

Palden Lhamo is an avatar of creativity we would do well to respect, because all of us who create, all of us who produce, all of us who bring forth into the world something that takes on form beyond us, are to a certain extent engaging with the forces she embodies. We are all charging around on the mad mule of our ideas, leaping between times and cultures. We all, as artists, make work only through a daily confrontation with our demons — our doubt, our fear, our shrieking uncertainty — and so we wear those vanquished ghosts just as she does: as adornments and talismans, amulets to ward off future hauntings. But because the world in which we live too often depends on permanence for meaning, the shadow side of our creative process is disrupted. Our books, our ideas, even our former selves, don’t fade and die as they naturally should. If we want to be free of them, as we must be to embrace what’s new, we must radically intervene, and kill the things we’ve made.

It’s not just the form of Palden Lhamo that speaks to something in our materialist creative present, it’s her depiction. In this age of likability and relatability, up-lit and escapism, Tantric painting and sculpture provides for us a model of art fiercely at odds with many of our assumptions and professed desires. This is not art that aspires to easy acceptance, or that offers up uncomplicated affirmation for swift digestion. It is art that thunders towards us across an ocean of blood, that feasts on the entrails of who we are, that crushes in its jaws the rotting corpse of our culture. It is art that terrifies, appals, disturbs, but which does so always out of love, and always because it knows: the world can be better, we can be better, and to be shown in an undistorted mirror the true horror of what we might be is an act not only of compassion, but emancipation.

When I finish a novel, one of my favourite routines is to clear away its detritus. I bin old drafts, re-shelve books, wash down the desk. I like my space to be cleared and cleansed, ready to receive something new. It is, I suppose, my own little ritual of destruction. It is also, though, an act of faith — one I’m only slowly coming to understand. The unwritten, perhaps unwritable novel that hovers always at the edge of my eyeline is, I’ve no doubt, a mirage. But it is a mirage I believe in, and because I am devoted to it, it sustains me.

This time, for the first time, something has survived the post-novel purge: a picture of Palden Lhamo, glowering down at me from the wall, reminding me always to destroy what I’ve made, always to make something from what I destroy, and always to wear my demons and obstacles as adornments.

And the novel itself, or at least one of its beautiful, hardback incarnations, is in the garden, left out for the birds and the foxes. In the morning, before I start work, I visit it, and watch it rot.

Sam Byers

Feature image: from the Wellcome Collection

Sam Byers’ Come Join Our Disease (Faber) is available to buy now from Burley Fisher, and Perfidious Albion and Idiopathy from Foyles