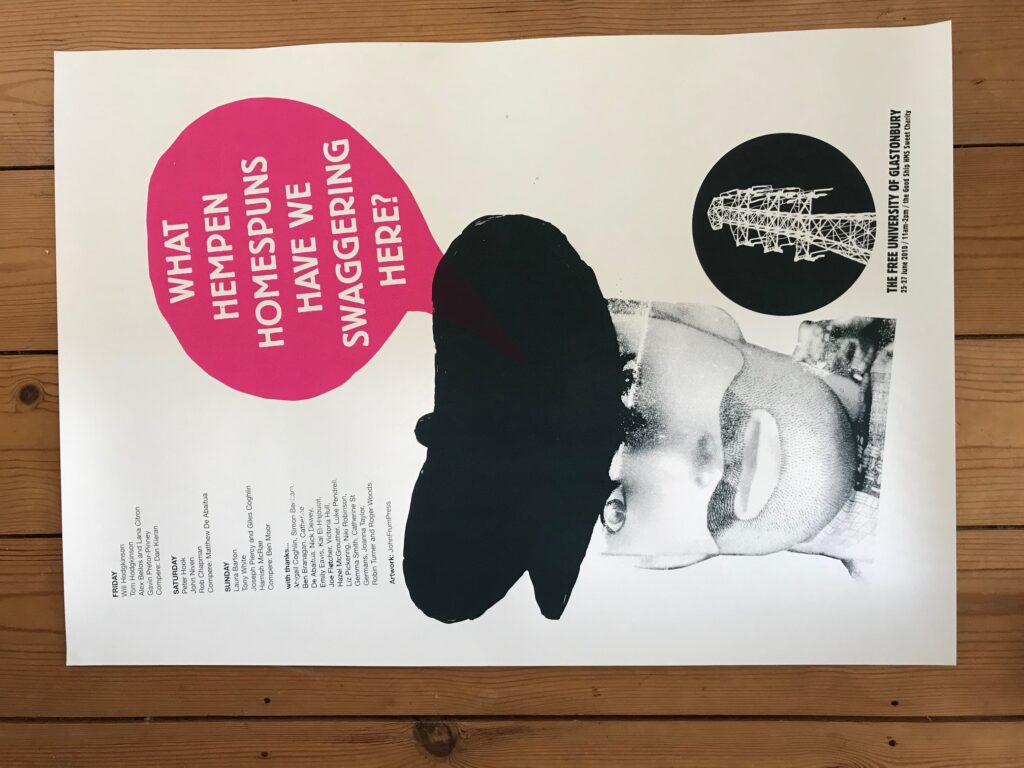

11 years ago Mathew Clayton and his friend Simon Benham set up the Free University of Glastonbury, a programme of talks from authors, musicians and other full-time dreamers that takes place each year in the Crow’s Nest in the Park.

‘What hempen homespuns have we swaggering here, so near the cradle of the Fairy Queen’

A Midsummer’s Night Dream by William Shakespeare.

Part One – Go West

The phone in the hall rang. It was the school with my A-Level results. Three Ds. A sinking feeling. D for dunce. D for dummy. D for didn’t work hard enough. I wouldn’t be going to university after all. How could I have done so badly? Even in English? We had been studying A Midsummer Nights Dream. It was my favourite play and I practically knew it by heart. The disappointment hung heavily. That night I went across to the Adastra Park to see if any of my friends where around. I headed to the bench in the far corner underneath the ancient oak tree and, sure enough, my best friend Joe soon appeared. I told him my news. What was I going to do? He had a simple answer. Let’s all go to Glastonbury. A little bit of calling round and amazingly everyone seemed to be up for it.

A couple of days later we all trooped into Brighton and bought our tickets from the Peace Centre on Trafalgar Street. My friend Dom was in the Sea Scouts and he managed to liberate a tent from their stores. Everything was falling into place – who cared about the future, I was going to Glastonbury. And best of all, the Chills were playing. I loved the Chills more than any other band but they were from New Zealand so I had never seen them live. Only one problem remained: we didn’t know where Glastonbury was or how to get there. It was time to consult the village elders – a gang of long haired, leather jacketed Gong fans that called themselves The Hassocks Heads. They were a couple of years older than us and Stonehenge and Glastonbury veterans. We found them loitering, as usual, on the bench outside Lavelles the newsagent.

‘Are you lot going to Glastonbury?’ I asked.

Derek Batchell looked up, ‘Nah, not this year, we have bigger fish to fry’.

‘What do you mean?’ I asked.

‘You know Gordon’s parents took down their big greenhouse?’ said Derek.

‘No, I didn’t’ I replied.

‘Well, they did. We’re going to reassemble it on the top of Devil’s Dyke as a pyramid. When the sun hits it on midsummer’s morning. Boom. It will create a giant sunbeam of laser-like intensity. Nigel reckons it will blast through the South Downs and… we hope flood the whole of Sussex. Well that’s the plan, anyway.’ I looked up at Nigel. He wasn’t giving anything away.

‘It sounds… ambitious?’

‘Not really. Anyway, what’s this about the Vale of Avalon?

‘How do you get there?’ I asked.

‘How do you get to the Vale? It’s easy. GO WEST. Just get any train headed in that direction and you will find Glastonbury.’

The rest of the Heads nodded sagely. We pushed off home for tea. I wasn’t convinced but everyone else was just happy not to have to think about it anymore.

Later that evening and still worrying about our travel plans I headed back to the Park. There was one person whose advice I valued. He wasn’t really a person, although he spoke like one. He was a Fox. My friends and I spent our life in the Park, day and night. Sometimes we would be there until dawn. One night, Fox had ambled over and joined us. It took a few weeks before he spoke, but by then we were used to his presence and it didn’t seem a big deal that an animal was talking to us. So, I went into the Park, sat on the bench underneath the oak tree and sure enough Fox appeared.

‘Fox, we are going to a place called Glastonbury tomorrow, the Heads have told me just to get on a train going west. But… that seems a little vague. I am worried we will get lost.’

Fox’s face lit up.

‘I know this place Glastonbury or at least somewhere nearby. In foxlore there is a magical valley nearby. It’s like your Shangri-La or Avalon – your people would describe it as a land of milk and honey although us foxes see it a little differently. It’s a hidden vale of endless riches guarded over by a Faerie Queen. A place many foxes have sought but few have ventured. I can’t leave Sussex this weekend – I sense a possible threat. I can feel it in my fur, but I know someone that might help’.

He let out a soft bark. And down from the oak tree above came fluttering an old crow, landing just a few feet away. They engaged in a conversation, the crow getting more animated the longer it went on. Then he spread his wings and flew back up into the tree.

‘Crow is getting ready for his final flight. He says he will take it with you. It’s his time. He is flying west into the sun. But as a favour to me, he will guard you on the way.’ I knew better than to question Fox. I had no idea how Crow would help us but if Fox said he would help then I knew he would. I thanked him before I turned to go, ‘Fox, that threat to Sussex. I think it could be the Heads. They have a mad plan to destroy the South Downs’. Fox pricked up his ears, then shook his head. I went home to bed.

That Friday morning, we dragged the scout tent up to the station and got on the first train heading west. Then the next one. Then the next one. We hopped from train to train following the sun. Out of the window I could see Crow flying high above us.

It didn’t work.

Journey’s end that day was Yeovil. Where is Yeovil? I still don’t know. We were all taken by surprise that the trains had stopped running and we were still nowhere near Glastonbury. How could the Heads have given us such bad advice? Or more to the point why had we believed them. Crow appeared. We followed him to patch of wasteland tucked round the back of the station and pitched the tent. Miraculously the next day we did make to the festival. Crow led us up a steep hill to a place away from the crowds with an extraordinary view over the festival. We set up camp. I could see Crow was getting weary. Next to us was a long hawthorn hedge with an ash tree towering above it. Crow sailed up into the canopy. Over the weekend I watched him build his final nest. And then on Sunday he flew down and landed on the ground a few feet in front of me. He lowered his head to the ground, let out a final craw. And he flew up, up and away.

Me and Joe walked off to see the Chills. They were shit but it didn’t dampen our spirits – we had learnt an important lesson: Glastonbury wasn’t about seeing the bands. If anything, they were a bit on an inconvenience, getting in the way of the other stuff… meeting the hippy that was trying to convert the world to candle power, the piano half buried in the ground, the burning car even Joe Banana’s blanket stall. All the wonderful madness that was Glastonbury.

When we got back to Hassocks I was walking back home from the station I passed Lavelles. Derek Batchell was sat outside looking uncustomarily glum.

‘Mathew. You made it back, you must have made it there.’

‘Hey Derek, yup we got there. It was ace. How did it go on Devil’s Dyke?’

‘Blow out man. Nigel has been obsessed with pyramids for the last couple of years after reading a book by some cat called John Michell. It was all his doing. So, we haul the greenhouse up to the Dyke. Start putting the thing up. It’s like 4am. But then I look round and there is smoke everywhere and running through it towards me looking completely mad is Nigel. He has lit a fucking field. It looks like ‘Nam. Flames as big as houses. We all pegged it. I think Nigel is just a pyro – no-one is talking to him. Gordon is furious as we had to leave the greenhouse behind. His parents went ape. The fire was on South East News.’

Part Two – Mrs Eggs

In the early 90s, I got a job working in the Guardian’s Marketing department. There was a gang of us. We were all in our 20s. Our mission was to rid the newspaper of its sandals and social workers image. One way of doing this was with sponsorships. A deal was done to sponsor Glastonbury who were also emerging into a new era. At that time, the standard practice of any sponsorship was to try and plaster your logo as large as possible everywhere you could. Glastonbury, quite rightly, recoiled at this idea. ‘Maybe we could do something editorially instead?’ they politely asked. My friend, Gavin, fed up with the colossal size of the existing programme, wondered whether we could produce a mini guide that you could keep in your pocket. I suggested that rather than hide it away we should distribute them in plastic wallets like the Visitor’s badges you get given in offices. That way, everyone at the festival would be walking round displaying the Guardian logo all weekend.

The mini guide was designed and printed but we had to take them down to Worthy Farm before the festival started. We dropped a car load of boxes to a portacabin but as we left a weird thing happened. We were walking back across the site to my car when I spotted someone I knew. Nigel from the Heads. I hadn’t seen him for at least ten years. But it was definitely him. He was walking towards me. As he came close I greeted him, ‘Nigel, man, how are you?’ He looked startled.

I tried again, ‘Nigel, it’s me, Mathew, from the village’.

‘Sorry mate I think you have got the wrong person’. He scuttled off. I thought nothing of it until late that night on the news I saw that disaster had struck Glastonbury. The Pyramid stage had been burnt down.

This new era meant free tickets and a temporary end of camping. Our gang from the Marketing department hired a holiday cottage on a farm just outside Pilton. It was down a series of tiny twisting lanes and almost impossible to find. The best way to know you had chosen the correct series of turns was a field half way there that contained a very amorous donkey. If you saw the donkey you going the right way.

The farm was run by a Ma Larkin figure who introduced herself to us as Mrs Eggs. We stayed there every year for five years and she never told us her real name. She had the wholesale contract to exclusively supply all the eggs to the festival. As you can imagine, this was a colossal amount. All around the farmyard chickens were running free. They were everywhere; bursting out of hedges, pouring in and out of the farmhouse. Mrs Eggs spent her days continually ferrying her wares back and forth to the festival in an old beaten up Volvo estate. If you were lucky, a trip back to the festival would co-incide with one of her egg runs and you could cadge a lift. It was on one of these trips looking back on the farm that suddenly it all fell into place. A valley full of chickens. This would be nirvana for foxes. Had I stumbled upon the hidden vale that Fox had told me about all those years ago? Was Mrs Eggs the Fairy Queen he had talked about? I had to ask.

‘Mrs Eggs, I am going to ask you something that might seem a little weird’.

‘Go on dear? I am all ears’.

‘Are you a Fairy Queen?’

I felt her body tense. The air felt hot and close. Maybe it was just the sunlight flickering through the trees but I thought I saw her face changing, flitting from her normal appearance to something impossibly old. She briefly turned to me and said in a sorrowful voice.

‘Maybe I once was’.

I said nothing further. That was the last lift she offered and in the following years I could tell she tried to avoid me. I told no-one about this strange encounter.

Part Three – Ten Years After

I was in the wood when I got the call. Tanglewood was a house my grandfather had built in Sussex during the second world war, when he sold it he kept a small strip of neighbouring wood. I used to go back there to collect firewood. I answered the phone, it was wife with bad news – my mother had been taken into hospital. A week later I lost my job.

The next weekend pushing my son round Peckham Rye trying to get him to sleep I wondered how I could pick myself up. In the middle of the Rye was a little stone bridge that went over a stream. My son peered down into the rushing water. We used to play a game where we would pretend to see things in the water. Look he said a fox, and there a crow. It wasn’t quite Blakeian proportions but it was enough. Glastonbury. I should go back to Glastonbury and I had an idea of how I could make that happen.

Mathew Clayton