In 1968 Vashti Bunyan set out on a journey that still resonates five decades later. Today we’re publishing the first in a series of regular posts by Vashti at The Social Gathering, beautifully illustrated by the author herself.

I needed a way to keep my dog and not lose my mind. I left home – to live in a bush in a wood with an art student I barely knew.

In that early summer of 1968, after falling from my father’s grace, I took the bus to Bromley Common, followed the directions that Robert had given me, past Ravensbourne College of Art, down a long path into a springtime wood.

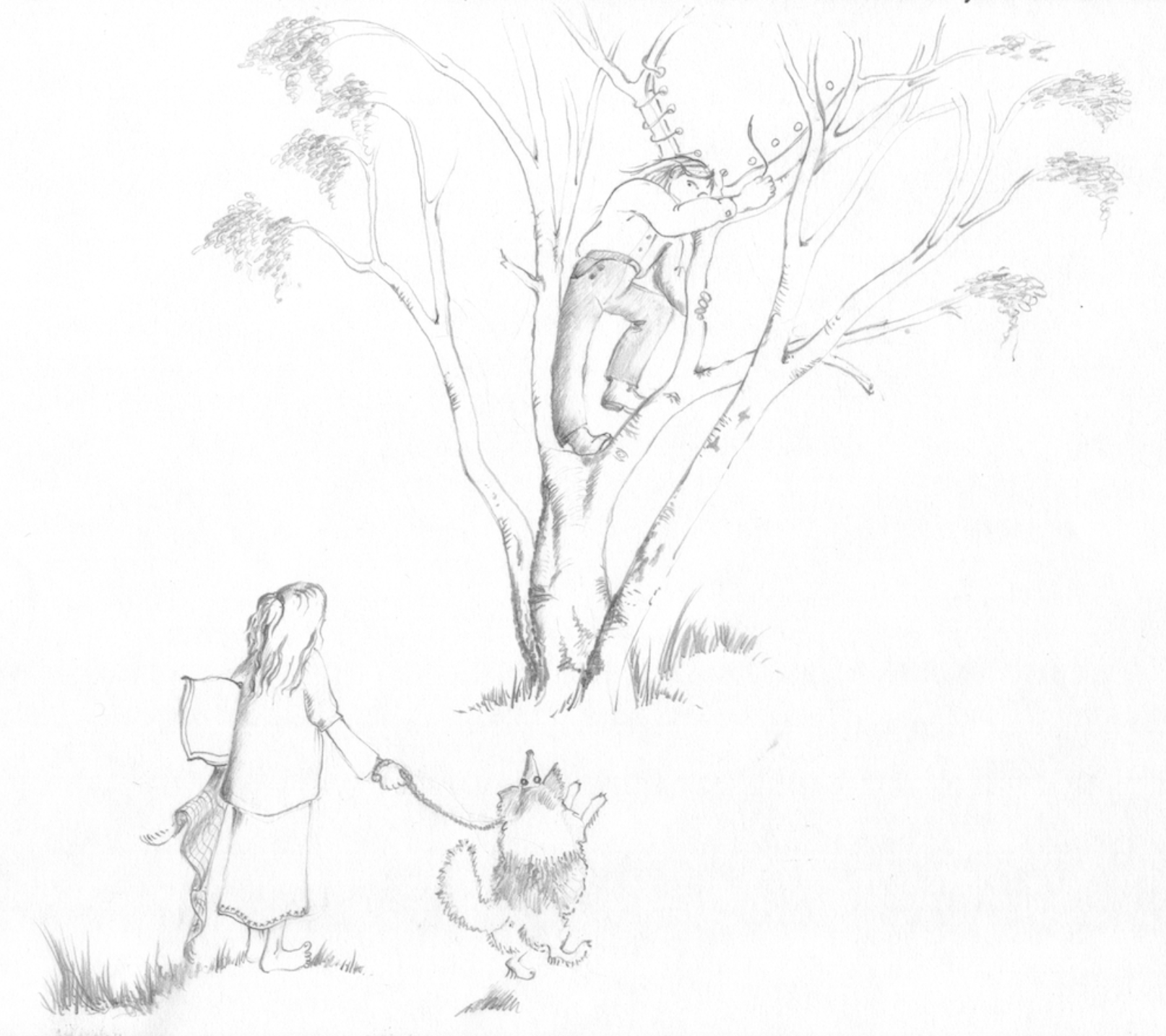

I stood with my dog on a lead in one hand and a pillow and plaid blanket under my other arm, looking up into a small birch tree where Robert was stretching a canvas between its branches with garden twine. He had already stretched a canvas under a rhododendron bush, which I was about to move into with him. He looked uncertain.

He was in his last semester at the art school which he attended against his parent’s will, he had no money and so nowhere to live and was tired of sleeping on other peoples’ floors.

He had a diploma show to set up which was to be the table and chairs he would make in the wood and the paintings on the stretched canvasses in the trees. He was ‘living underneath a picture and then making life the picture’.

He had laid a small square of carpet on the earth in the bush, and on top of that there was a single green mattress. I added my pillow and blanket. We gathered a saucepan, breadboard and knives over the days, I found a roll of muslin in a junk shop and made curtains to go around the whole house. We cooked young nettles in the old saucepan over the fire. We needed salt – which we took from the art-school canteen.

Robert’s friend John James thankfully had a kind mother. Rose had three sons; John was the youngest. They lived in a long road of semi-detached houses in Barnehurst, and the houses were identical – but for John’s house. There were the remains of two 1930s Austin 12s in the garden whose parts had gone to make up the third – Happiness Runs (named after a Donovan song) – which stood at the door.

A visit to John’s house meant pie and beans within moments of arrival, and after a few penniless days in the wood eating nettle soup I looked forward to seeing Rose. She reminded me of the best things about my own mother. Dark haired and dark eyed, direct, generous and funny.

John’s bedroom was crammed with everything that Rose had ever bought at a jumble sale, like two large cardboard boxes of ladies’ size 10 shoes, some of John’s paintings, a few of Robert’s – and Robert’s clocks.

He bought and sold them, along with silver pocket watches, ethnic weapons and oil lamps, to pay his way through Art School.

On our return one dark night to our rhododendron house we found our bed had been soaked in paraffin from the oil lamp, and Robert’s best silver watch was gone. There was no way to get back to John’s house so late. We stung all night and in the morning we awoke to boy voices. Robert was in his ankle-length Victorian night-shirt. He had very long hair and he shot from the bush in his bare feet waving a Fijian war club, roaring as loud as his rage would let him. The boys went white and fled, stumbling through the trees with Robert crashing behind them. He came back looking pleased with himself.

Half an hour later we had a visit from two policemen and a man in a grey suit. The representative of the Bank of England whose land we were on politely asked us to leave. “What if everyone were to want to come and live here?” What indeed.

The two policemen meanwhile had been rummaging in our rhododendron-bush home, and emerged triumphant with an old and ignored court-summons which Robert had amongst his few belongings. He had been stopped three times between London and Suffolk on an uninsured, untaxed motorbike with just a Learner plate which would not have allowed him to have a pillion passenger. Which he did.

We were instructed to pack everything up and were then escorted to the far edge of the wood. Our small green world with birds and primroses there opened out into a housing estate where the new white houses gleamed straight sided and raw. This was where the boys had come from, had run ashen-faced and screaming back to and from where their parents had phoned the police, reporting a wild man in the woods. Robert was handcuffed to one of the officers who was talking on his radio, while the other asked me if I had anywhere to go while Robert got a few months inside.

The summons was more than six months old, a small detail they had overlooked, and so we were free. The police car sulkily drove away, leaving us standing on the side of the road with the dog, my guitar, an oil lamp, saucepan and a bow-saw, a Fijian war club, bright green mattress, blanket, pillow and an eighteenth century silver teapot lid.

The rest of that teapot had been hurled by a raging Robert into a bush when he’d seen that I had melted a hole in the spout by the fire. He had ripped off the lid first which we kept, and years later, when I knew about these things, I saw that the hallmark could have told us that he had owned a very valuable London made piece of silver which would probably have paid all of Robert’s long-owed art-school fees and left us some over to rent a house with. How different things might have been.

As it was, I walked to the phone-box to sadly summon John and Happiness Runs. While we piled all our household goods into the back it came to us that a good way to get over our present problems would be to have a house permanently on wheels. “What about petrol?” asked John, who had a problem with it in that he only put a little at a time into his car on the basis that the less he put in the less she would use.

“We’d need a horse,” said Robert.

Happiness ran out of petrol.

We all knew the shortest route to the nearest garage by now so got out to push. As we were resting on the Sidcup By-Pass, leaning against the back of the car in the evening sun, there was a gap in the wooden fence just where we had stopped and through this I spotted an old wheel. On closer inspection we found that it belonged to a broken-down horse-drawn baker’s van with a canopy over the front seat and little oval windows in the side.

Ten yards away was a new bright white and chrome Traveller’s van with cut glass sprays of flowers on the windows and a half door. Over this door leant a large man who watched us coldly.

“We’re looking for a cart like this, is it for sale?”

“Might be.”

“Do you know where we could find a horse for it?”

“Come back in the morning”.