July 1968.

London Garden

Our first stop in London was in Islington where Robert’s one-time tutor and now friend Anthony Benjamin had a large home and studio. We parked the wagon on the side of the street, walked Betsy the horse through to the back garden and let her loose on the grass.

Anthony and Nancy’s upstairs neighbour was a sculptor whose artwork stood about the garden. Welded sheets of rusting iron were perfect for Betsy to scratch her backside against, making them rock. The second floor window shot up and the sculptor shouted at us to “get that fucking horse off my work”. I thought it was funny but his shaking fist and red face made me have to learn to be a bit sorry and so we tied the horse in another part of the garden.

Deciding that this was the beginning of the next part of our lives we emptied our possessions from the wagon onto the grass and went through it all, making a bonfire of everything that was not important any longer. Like all my writing and all Robert’s writing. Pretty shoes no good for walking in. Books that would be heavy for the horse.

I often think of that bonfire and all that we lost of our young selves. Robert leant in and rescued a few pieces of paper. I have them still, burnt around the edges.

Betsy lost a shoe.

******************

Islington High Street, London

I wore my late aunt’s 1930’s nightdress, nothing else. Nothing on my feet and a pink crepe bias-cut flower printed nightdress long enough to trip me if I didn’t hold it up. My hair was long too – dark brown, unbrushed – and I led a fat black horse with a white star, a short tail and one missing shoe.

My main concern was that she should not tread on my toes, but her big feet were always thoughtfully placed.

Right now we needed a blacksmith and our directions took us down Islington High Street – with people staring out of buses and stopping on the pavements to watch us go by as Robert, Betsy and I looked for the Whitbread Brewery. There, we were told, they had a stable of grey Shire horses who – six at a time – pulled the giant drays around the streets delivering barrels of ale to the pubs. These horses had their own forge up in the far corner of their stable – a stable as large in scale as they were with their names like High, Gog and Magog and their feet the size of frying pans.

“Hello Bess” said the blacksmith as we walked towards the forge – the dusty sun in my eyes from the big high windows.

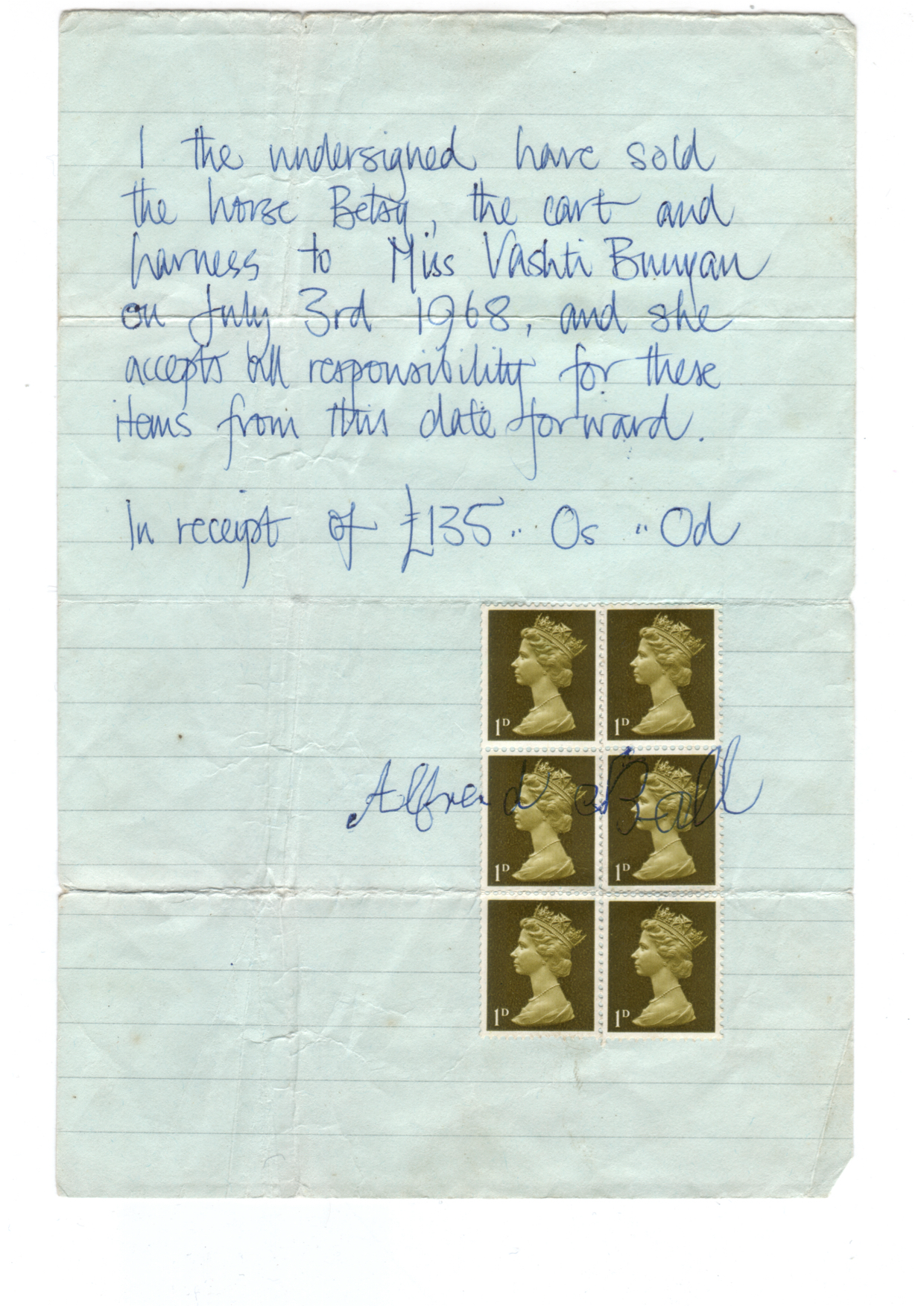

We thought her name was Betsy. The Romany Alfie Ball who had sold her to us the day before had called her Betsy.

“na – that’s old Bess – I’d know her anywhere.”

Old?

We’d had a friend who knew about horses give her a looking over and she’d been pronounced young enough. About ten maybe.

It turned out that Bess must have been born before the law on docking horses’ tails was passed, making her twenty or more. He showed us how her teeth proved his point. She had seemingly lived her long life out on the streets of London pulling delivery vans. Bakers, grocers and latterly a flower seller had all taught her traffic wisdom, which was just as well for us when she stopped at traffic lights and knew her way around roundabouts.

The smith made four shoes of iron – red-hot from the fire – banging them into shape on the anvil whilst telling us she would need them specially built up on account of her habit of turning her back feet with every step. This would wear her shoes down quickly.

He didn’t ask us for any money, just a tune or a song. Robert looked at me – the singer – but I turned my head away. Robert had a harmonica with him and so played a bit of a tune and danced around the stable in his boots with the flapping soles. I watched through my fingers, in my aunt’s pink nightdress, thinking how can a grown man dance like that – as if around a toadstool – without feeling daft. He didn’t care at all. I think at that moment he thought himself a little creature, small and elven with leggings and perfect, pointed, soft green shoes.

Everyone there, the blacksmith, the stable boys and the dray drivers all enjoyed the show, we made our grateful goodbyes and we led Betsy – the little old horse we had thought so large that morning – out past the soaring grey backsides of the Whitbread Shires and into the Islington streets.

She would be Bess from now on – her real old name.

Vashti Bunyan