Peter Laughner is dead. That’s the first line of the greatest piece of music writing I ever read, “Peter Laughner”, by Lester Bangs, re-published in Bangs’ seminal collection, Psychotic Reactions and Carburetor Dung in 1988 when I was 17 years old. Lester Bangs is dead, too. Yet I have lived with Bangs and Laughner ever since, to the point that I still wonder, every so often, when I score an amazing new book or a brilliant new LP, what the two of them would have made of it.

Laughner died in the early hours of June 22nd 1977, after recording Nocturnal Digressions, a haunted solo cassette that would be one of the most iconic 1977 recordings had it been released at the time. Now available as part of Smog Veil’s Peter Laughner box set, it makes for an uncanny, uncomfortable listen. “I understand all/destructive urges/they seem so perfect,” Laughner sings, his voice cracked and made haggard from hard liquor and Lucky Strikes, on an otherworldly cover of the band he almost made second guitar for, “See No Evil” by Television. But then, Laughner never really made much of anything; dead, at the age of 24, from acute pancreatitis brought on by alcoholism and drug abuse.

Then why I am so fascinated by both Bangs and Laughner? I think, perhaps, they were the first generation of true believers to take rock at its word, and to take it seriously; Dylan, Lou Reed, Van Morrison. Alongside people like Paul Williams (and in Scotland, Brian Hogg and Lindsay Hutton) they were the generation that birthed rock n roll fandom. Rock music transformed their lives, led them to poetry, fashion, literature, excess. Plus, if I could be in any band ever, I would be a member of the original Rocket From The Tombs, the band that Laughner and David Thomas (aka Crocus Behemoth) re-birthed as Pere Ubu, one of the truest marriages of raw rock n roll and freakout avant garage. Laughner was a great writer, too. Who could forget the opening salvo from his notoriously scabrous review of Lou Reed’s Coney Island Baby in Creem? “This album made me so morose and depressed when I got the advance copy that I stayed drunk for three days.”

But it’s these lines, of Lester’s, that have stayed with me since I first read that Peter Laughner was dead back in 1987: “… I will not forget this kid killed himself for something torn T-shirts represented in the battle fires of his ripped emotions”. That’s me, I often think. That’s the energies I re-channelled into my first novel, This Is Memorial Device.

I first heard Laughner’s music on a (bootleg?) 7” co-released by Forced Exposure and Bill Shute’s Inner Mystique in 1987, “Cinderella Backstreet.” Which is exactly what a Lou Reed nut would name his band, but it’s also the title of this amazing song by Laughner, just about one of the most forlorn outlaw ballads this side of Dylan, all these new forms of life, in the lyrics, these creatures, revealing themselves, in the darkness, to Laughner, as he walks towards it. And for so long that was it. I heard a rumour of a Bangs/Laughner jam, a cassette that was doing the rounds, but was never able to score a copy (that dream session does exist, though, and it’s as good as you might have hoped, bundled as a cool 7” EP with pre-order copies of the Peter Laughner box). Then in 1993 Tim/Kerr released the brilliant double LP retrospective, Take The Guitar Player For A Ride. As well as “Cinderella Backstreet” and “Baudelaire”, which I knew, there were revelatory Dylan and Neil Young covers, Rocket From The Tomb’s original version of “Ain’t It Fun” (later covered by Guns n Roses) and a selection from other bands, including Friction (with an incendiary take on Richard Thompson’s “Calvary Cross”) and The Fins.

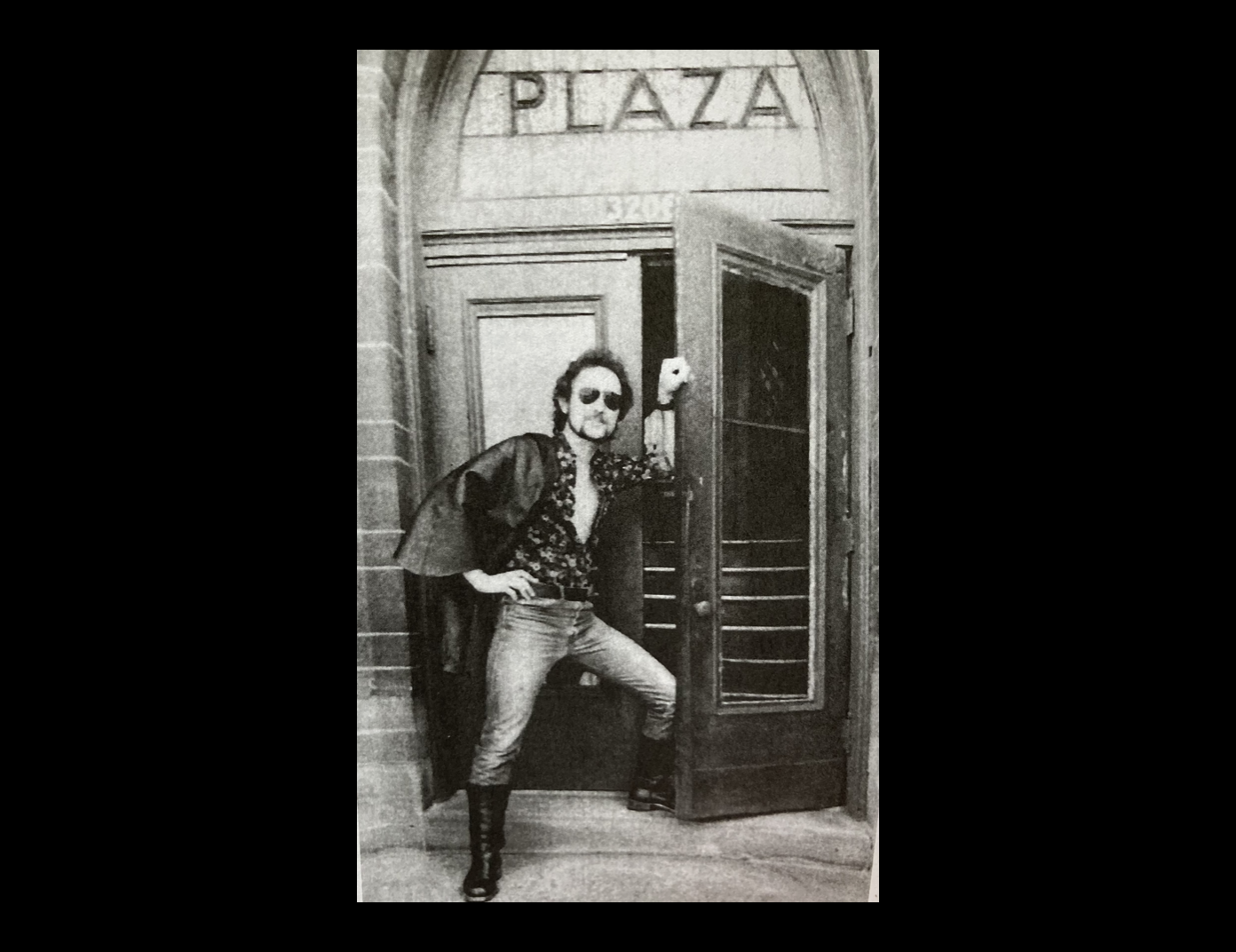

But it’s really only in the past few years that Laughner has stepped out of the shadows, a little, at least, and it’s entirely down to the work of Smog Veil Records, who have unearthed a jaw-dropping series of tapes for their definitive Peter Laughner box, as well as incredible photos, reviews, and ephemera for the hardback book that accompanies it. And now this, which might be the best of all: Laughner’s friend Adele Bertei, who played with him in Peter and the Wolves and who went on to join James Chance in The Contortions, remembers the short time they spent together in a book that is truly one of the great – and most moving – rock/roll microhistories, Peter And The Wolves, newly published by Smog Veil.

It’s a story of arrivals, of constant arrival at the brink of the future, again and again. Adele flees a troubled childhood and bumps into Peter Laughner at an open mic night and the whole world opens up. Her description of Peter’s room, when she first goes over to visit him, is just so luminous with the magic of the times: Peter’s guitars all along one wall; the reel-to-reel; the classic stereo; on the table the neatly-piled copies of Creem and outlaw Cleveland poet d.a.levy’s Third Class Buddhist Junkmail Oracle; how they jam guitars to The Stooges’ “Down In The Street” and listen to records by Roxy Music and Eno… I wept, as she walked into Peter’s room for the first time, I have so longed to see it myself, and I cried again when she talked about the records they would sit up all night listening to, because they were the same ones I did. Iggy, MC5, the Velvets for late at night; Richard & Mimi Farina, Joni’s The Hissing of Summer Lawns, Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde for the early hours. And his books, too: Burroughs, Lowry, Kerouac. I could re-read these pages forever.

They arrive in New York, arrive at Lester Bangs’ pad, arrive at CBGB’s. Lester takes them on an underground NYC guided tour: the women’s jail that held Valerie Solanas and Angela Davis; Electric Lady Studios; The White Horse… At 4am Lester plays her Mingus’s Black Saint and the Sinner Lady. “Thinking of the possibilities these boy-men were unselfishly exposing to me,” Bertei writes, “I felt a strange fear at being in love with it all.”

But Laughner’s drug use and his drinking is increasingly out of control. I remember Bangs mentioning a time when Laughner and his father had both turned up at his door, roaring drunk, and Bertei makes it clear that, as well as passing on the disease, Laughner’s father did nothing to discourage his drinking. In fact, they were drug buddies.

There are some amazing stories here. Laughner is on the phone to his pal Richard Hell when the conversation turns sour. Laughner leaps off the couch and let’s fly with a couple of shots from a German handgun gifted to him by his ex-army father, the same model that Hitler used to put a bullet in his head. Bertei hits the floor as the bullets ricochet around the room. What are you doing? she screams at him. I’m sorry, he says, I was trying to shoot Richard Hell in the nutsack. Sure enough, there’s a photo of Richard Hell pinned to the wall with a bullet hole straight through its crotch.

Then Laughner gets kicked off stage at CBGBs trying to join Television, or was it Patti Smith? And so he travels back home, and he records that final haunted tape, and he goes to bed, and he dies.

Bertei, who went on to be a successful session player and backing singer, asks herself, early on, why she didn’t create more, why she didn’t make more creative use of her time, and she answers that, well, she was afraid to be solitary, really, she was afraid to be alone, and to create from there.

I’m listening to Nocturnal Digressions again. How many nights have I spent with this lonely recording? I’m drawn, once more, to Laughner’s version of American singer-songwriter Jesse Winchester’s otherwise-unremarkable “Isn’t That So?”. In Laughner’s hands it comes on like prophecy. “Didn’t he know what he was doing, putting eyeballs in my head, if he didn’t want me watching women, he’d have left my eyeballs dead,” Laughner sings, as though hypnotised by himself. And then: “Didn’t he know what he was doing, when he made the magic vine, his own son got a reputation, turning water into wine.” And again: “Line of least resistance lead me on, lead me on, line of least resistance lead me on.”

You’ve got to go where your heart says go, isn’t that so?

David Keenan