The big question with any super deluxe edition of a legendary album is whether it’s better than the myth. Often when you hear all the outtakes or additional tracks from a record it can demystify a beloved album in a disappointing way. It’s also hard to know where to draw the line and who to satisfy with a box set. Present too few outtakes or slightly altered less good versions of the original albums (as with the recent David Bowie box sets) and you risk turning off the faithful. Follow the completest approach and offer endless alternate takes of the same few songs (as with some of the Beach Boys boxes) and you have an artefact that will only appeal to the most obsessive of collectors.

But the Sign O’ The Times box set will satisfy everyone. The world’s greatest album is now the world’s greatest box set, as perfect a gift for the Prince obsessive as for a music fan hearing his music for the first time. Yes, among the nine hours plus of material there are a few (but remarkably few) second-rate songs, and as fantastic as it is to have all the 12inch mixes and singles edits gathered up in one place (including beloved tracks such as the ten minute ‘Highly Explosive Mix’ of ‘La, La, La, He, He, Hee’) you’ll have to be in the right mood to listen to that part of the set in one go, but that aside, there’s nothing on this collection that is anything less than essential.

Still, it’s not necessarily what might’ve been expected. Even Prince’s former bandmates have expressed surprise that Warner Brothers and the Prince Estate have put out quite so much material in one go, and in this form. Here’s why it’s the right decision.

Sign O’ The Times is an utterly singular case: a perfect, unimprovable album where every track is ideally placed, and yet, at the same time, also widely considered an artistic compromise. For years, one of the hottest topics of discussion among Prince fans was the what-if scenario that might’ve played out if Prince had been allowed to release his original version of the album, a triple record called Crystal Ball. Did the Warner Brothers executives who asked him to slim down the package make a terrible mistake in denying listeners the extraordinary amount of high quality material Prince edited from the collection, or was sending Prince back into the studio to rethink, reorder and record a couple of extra songs a management masterstroke that kept Prince successful and stopped him drifting off into cultdom like other musicians Prince admired such as Todd Rundgren? Around this time Prince was considering himself equal to Orson Welles, and we all know how that ended.

The sleeve notes to this box set introduce a fascinating new wrinkle to the story. In an interview with estimable Minneapolis-based music writer Andrea Swensson, Lenny Waronker, the Warner Brothers President who signed Prince, claims that after hearing the proposed Crystal Ball he got angry about Prince’s self-indulgence and told the artist about Max Perkins, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s famed editor, and how much he had contributed to his authors’ books. But rather than propose himself as Prince’s Perkins, Waronker tried to bring out Prince’s own inner editor, telling him that he needed to separate his critical instincts from his artistic ones and deliver a more marketable record.

Whether this was an act of extreme understanding or a dereliction of duty is a moot point in relation to Sign O’ The Times. Taken as an individual case, it got the results Warner Brothers were looking for and took Prince to a whole new level of critical acclaim. But step back and this is an important way-station in Prince’s career as a whole, as he progressed from the point where he was perfectly happy to craft a couple of extra hits for 1999 to his deliberate submission of challenging material that helped destroy his relationship with the label in the mid-90s.

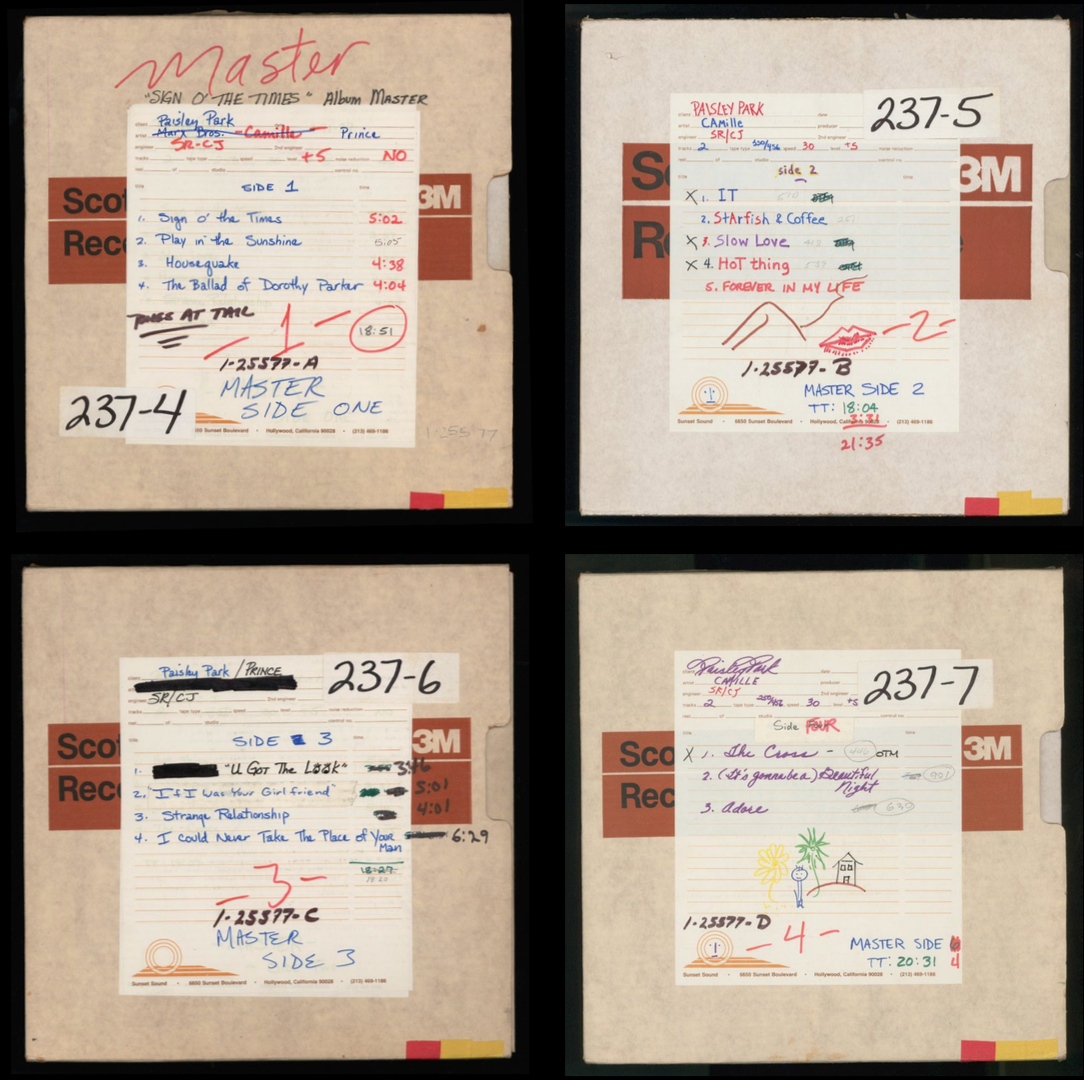

The story of how Crystal Ball became Sign O’ The Times has always been complicated by the fact that Crystal Ball was itself comprised of multiple songs from multiple other projects, including one album that does appear to have been completed and considered for release, Camille, and another, Dream Factory, that was more nebulous and may actually have been an intended musical.

Michael Howe, the ‘Archival Producer’ of this box set wisely avoids trying to piece together these past projects and instead the Vault material here is a massive info-dump of almost every track that can be tied into the era, including one major hitherto unknown find: a 1979 version of ‘I Could Never Take the Place of Your Man’, which shows that Prince was so far ahead of the game that a track he’d been sitting on for eight years sounded utterly fresh in 1987. Earlier versions of other album tracks like ‘The Ballad of Dorothy Parker’ and ‘Strange Relationship’ reveal influences that’d been deeply obscured by the final release. Although I’ve heard others maintain that Stevie Wonder was a strong influence on this album, I’ve never really heard it, but it’s much more apparent in these outtakes.

There are a few strange omissions, which are probably due to project overlaps: while the majority of music Prince recorded with Wendy and Lisa between the release of Parade and their departure from the Revolution is here (it’s nice to see them properly credited for their production work, and for the first time you can fully understand how devastating for them it must’ve been for some of the best music they’d ever been involved in to disappear seemingly forever), there are a few missing tracks (‘Go, ‘Empty Room’, ‘Splash’) that are presumably being held back for a future Parade box. Given that part of the story of Sign O’ The Times is the demise of Prince’s relationship with Susannah Melvoin and several of these songs directly address the relationship, it does feel odd that they’re not here.

The weirdest oversight is that the box doesn’t include any of the three major versions of the track ‘Crystal Ball’, either the edited version that was finally released in 1998, or the two longer versions with spoken word sections that have never been officially released but which circulate among fans. Instead they’ve included a truncated “7 inch” version that I’ve never heard mentioned before and I think may not exactly represent Prince’s intentions.

Given Prince’s habit of working over old tapes, I wonder if these were perhaps not in good enough condition to release (unlike with the Purple Rain or 1999 boxes everything here has come from the most optimal source). Or perhaps an executive decision was made (again, this could be due to rights issues) not to include anything from this era that had already received release on Prince’s confusingly named 1998 collection Crystal Ball, which also included two other songs you might expect to find here, ‘Dream Factory’ and ‘Movie Star’. This also means, sadly, we lose one of Prince’s best segues: the hilarious way ‘Movie Star’ runs into ‘A Place in Heaven’.

There is one other track that did appear on Crystal Ball, ‘Crucial’, but it’s included here in an ‘Alternative Lyrics’ version and there’s a ‘1985 version’ of a song that already appeared on the 1999 box set, ‘Teacher, Teacher’. One of the oddities of these expanded reissues is that slight pieces like this now stand alongside his greatest songs as if they are of equal significance. But it’s a small price to pay for such bounty.

Another truncated track is ‘Soul Psychodelicide’, presented here as the ‘1986 Master’ (again, a slightly suspicious wording) to distinguish from the hour-long jam it sprang from. This might upset completists but it’s a rational decision. Equally understandable, though slightly disappointing, is the decision not to include the more freeform of Prince’s jazz experimentation during this period, either the hours of unreleased material he recorded as a group known as The Flesh or any live or studio work from Madhouse, Prince’s jazz band which he used as his own opening act on the Sign O’ The Times tour. It may be that this is also being saved for a separate later set, and as compensation this box includes both Prince’s studio collaboration with Miles Davis, ‘Can I Play With U?’ and their appearance onstage together. I’ve seen some criticism from both Davis and Prince fans that ‘Can I Play With U?’ doesn’t do either of them justice, but the version here is a serious upgrade from previous circulating versions and for the first time you can really hear how Prince was trying to respond to Davis, the clarity of sound bringing a new perspective on their interaction.

For fans of this side of Prince’s work, there are also a number of more experimental jazz and classical influenced tracks scattered around the set that show Prince at his most ambitious (the fan favourite ‘In a Large Room With No Light’, an incredible rehearsal version of ‘Power Fantastic’, and two instrumental tracks that show off a band assembly previously underrepresented in his official oeuvre, ‘And That Says What?’ and ‘It Ain’t Over Til the Fat Lady Sings’). Alongside Wendy and Lisa, Eric Leeds on saxophone and trumpet-player Atlanta Bliss truly shine here.

Alongside tracks that were clearly part of the creative process that led to Sign O’ The Times,there are also songs initially intended for other artists. ‘Emotional Pump’, the song Joni Mitchell rejected, is much better than its reputation suggests and one of the highlights of the set, but a quartet of tracks for Bonnie Raitt seems a slightly odd inclusion, even if it is utterly delightful to hear Prince crooning about how much he needs a man and Professor Daphne A. Brooks makes a fascinating case in her essay that this was a natural extension of Prince’s interest in gender fluidity at the time.

There are also songs for at least two proposed musicals, a possible movie (The Dawn) and a number of genuine surprises, including a gospel song, ‘Walkin’ in Glory’, written on the same day as the Black Album’s ‘Bob George’ as an apology to God, and ‘Blanche’, inspired by the character names of the protagonists of A Streetcar Named Desire, but not, the sleeve notes sternly warn us, the action of the play or movie. I think Duane Tudahl, who is a largely meticulous and responsible sessionographer and provides details for all the Vault tracks here, slightly over-eggs this: while I’m prepared to believe, as has previously been argued, Prince didn’t make a connection between his Dorothy Parker and the famous writer (though Professor Susan Rogers questions this in her essay, pointing out how obsessed Prince was with early Hollywood at the time), in writing a song about Blanche and Stanley, Prince must’ve had at least some idea of what he was doing, even if only using them as an example of a warring couple. Speaking of stage plays that became Brando movies, it’s fascinating to read that the cryptic cover of the album was in part the set for a local dinner theatre production of Guys and Dolls.

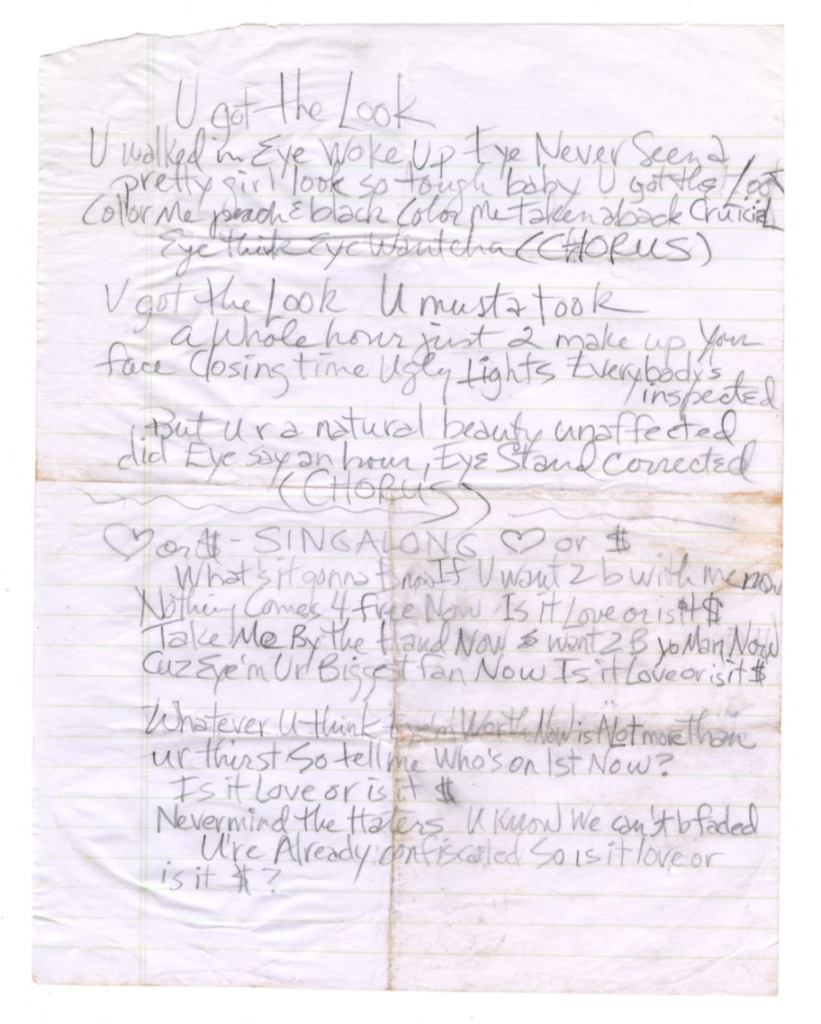

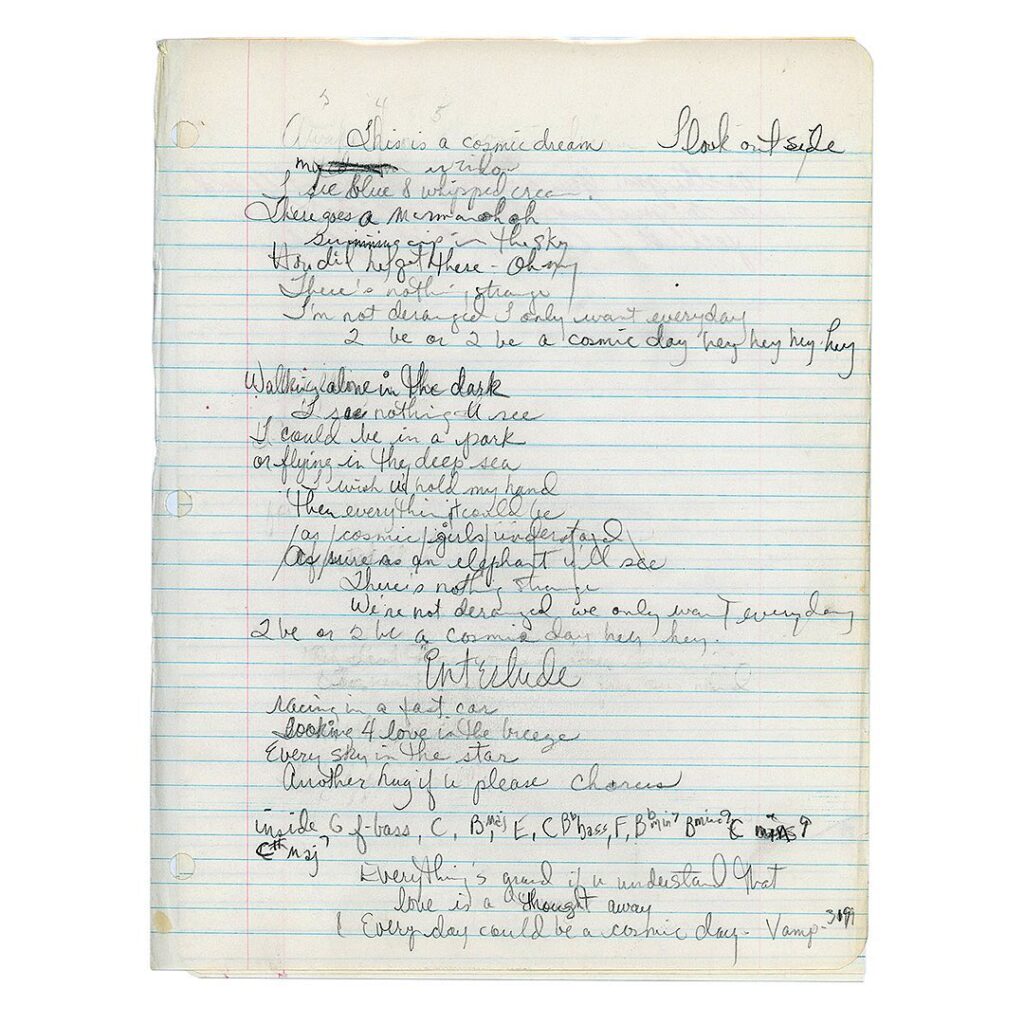

There’s so much here it will take years to properly process. I haven’t mentioned the pages and pages of handwritten lyrics that could provide sufficient material for a full Prince PhD; Jeff Katz’s astonishing photography (of all the many great photographers Prince worked with, Katz was among the finest) or the celebrity pieces from Dave Chapelle and Lenny Kravitz. Obviously I’m particularly drawn to the songs I’ve never heard before, but it’s worth pointing out that the album itself, which has long deserved a proper remaster, sounds better than it ever has before and among the Vault material that has previously circulated in some form, there are many of Prince’s greatest ever songs (personal favourites include ‘All My Dreams’, ‘Rebirth of the Flesh’, ‘Wally’, ‘The Ball’ and two versions of ‘Witness 4 The Prosecution’). I still find the lyrics of ‘Big Tall Wall’ creepy, but the first of the two versions included here seems like an almost completely different song and the darker undercurrents of these lyrics are responsibly addressed in the sleeve notes and interviews. This is a much preferable approach to the ahistorical censoring that marred the 1999 box. As was revealed by the recent leaking of an insane early Prince song, ‘Neurotic Baby Lover’s Bedroom’ from a totally different period, Prince had a seriously freaky side and kudos to this collection for not trying to cover it up.

One thing that is apparent, and this may be the ultimate proof of the full extent of Prince’s talent, is that even with so much material and so many distinguished guests trying to pin down what it all means, I’m still left with questions. If Prince’s alter ego was called ‘Joey Coco’ and this is the character that features in the song about him here, then why is it called ‘The Cocoa Boys’? I assumed someone had written it down wrong, but no, here it is in Prince’s own handwriting: ‘The Cocoa Boys’. What’s the full story behind the movie he was considering called The Dawn? Was Dream Factory actually more of a musical than an album? Is that why quite so many of the outtakes sound like musical theatre? Are we seeing the seeds here of what prompted Prince to threaten to stop writing albums in the 90s? If this is truly (and with the possible exception of Lovesexy, it really is) the peak of Prince’s career, then why does it feel so much like the end. Before it seemed like all the answers might be in the Vault, but now the Vault’s been turned inside out, it’s clear that the answers may never be revealed. And that’s fine: Prince loved preserving mysteries. ’Definitive’ just wasn’t in his vocabulary.

Often live material, especially in a box of this size, can seem like an afterthought. But that’s not the case here. It does need a bit of explanation. What’s not here, due to rights issues, is the Sign O’ The Times movie. As the film is easily available, this isn’t a great loss and what we have instead is equally valuable. Although it’s frequently referred to as one of the greatest live concert movies ever released, the Sign O’ The Times movie is a hybrid, with Prince taking the raw recordings from three shows in Rotterdam, overdubbing the sound and re-recording the show on a soundstage, with dramatic interludes. It’s also edited down to mostly remove old songs (aside ‘Little Red Corvette’ and a cover of Charlie Parker’s ‘Now’s The Time) and instead represent the album in visual form.

This has meant that this live era is underrepresented when compared to the subsequent Lovesexy tour. There were no American shows on the tour and the London dates were cancelled. Though bootlegs have circulated, as they do for most eras, fans have tended to focus on two video recordings: an initial run-through of show in Minneapolis (not included here) and a New Year’s Eve show with Miles Davis at the then relatively new Paisley Park complex. The latter is included here but in the absence of the former we have instead a complete show from Utrecht which reveals why the lucky Europeans who did see this show have always insisted this tour is undervalued. It’s significant that while so many British bands concentrated on cracking America to ensure their lasting reputations, at this period in his career Prince was focused on Europe and the converts he made on this tour stuck with him for the rest of his life, ensuring lucrative touring money never completely dried up.

My personal sense of this tour previously, going only from recordings, was that it was perhaps a bit stiff, with Prince so focused on reproducing songs that relied on studio trickery and breaking in his new band after abandoning the Revolution that it lacked his party side, but the Utrecht show destroys this argument. It might even be the bit of the set I’ll return to the most. While the Sign material does provide the spine of the show, it really takes off when he plays a Parade track ‘Girls & Boys’ and from then on the band don’t come back down to earth. It was also a blessed period when the big encore wasn’t ‘Purple Rain’ but the still astonishing jam ‘It’s Gonna Be a Beautiful Night’.

The DVD of the New Year’s Eve show is a slightly more curious document. Long treasured as a bootleg, it contains a genuine moment of history with Prince and Miles Davis onstage together and a whole lotta larking around, as Prince disses famous local music journalist Jon Bream, rags on his band and struggles to release balloons. But it also shows Prince getting Sign O’ The Times out of his system and working on bits of business that will become central to his subsequent Lovesexy tour, like the dance he, Cat and Sheila E perform to ‘Erotic City’.

So where does the Estate go next? I think that Parade box seems likely. The Lovesexy era is thin on unreleased songs, but it would be great to see a set including the official Dortmund live recording alongside his most famous bootleg, the Small Club show. The mid-90s could do with some tidying up. But the greedy fan in me would love something truly unexpected: unreleased albums like Welcome 2 America or Black is the New Black. Give us a box set of a hundred songs that we’ve never even heard about, or a set of live shows from under-represented eras. The Prince Estate and Michael Howe are serving Prince’s reputation masterfully, but let’s not forget Prince loved surprises and was anxious about spending too long staring in the rear-view mirror.

If it’s not clear by now, you need this box-set. Die-hards will have had it on pre-order since it was announced but fair-weather fans who don’t know just how much Prince produced in this era will get just as much out of it. In an earlier version of ‘Strange Relationship’ included here Prince asks for forgiveness for a relationship infraction because he’s only human. In the finished version of the album this line had gone, the artist clearly aware he had passed from human to superhuman.

Matt Thorne

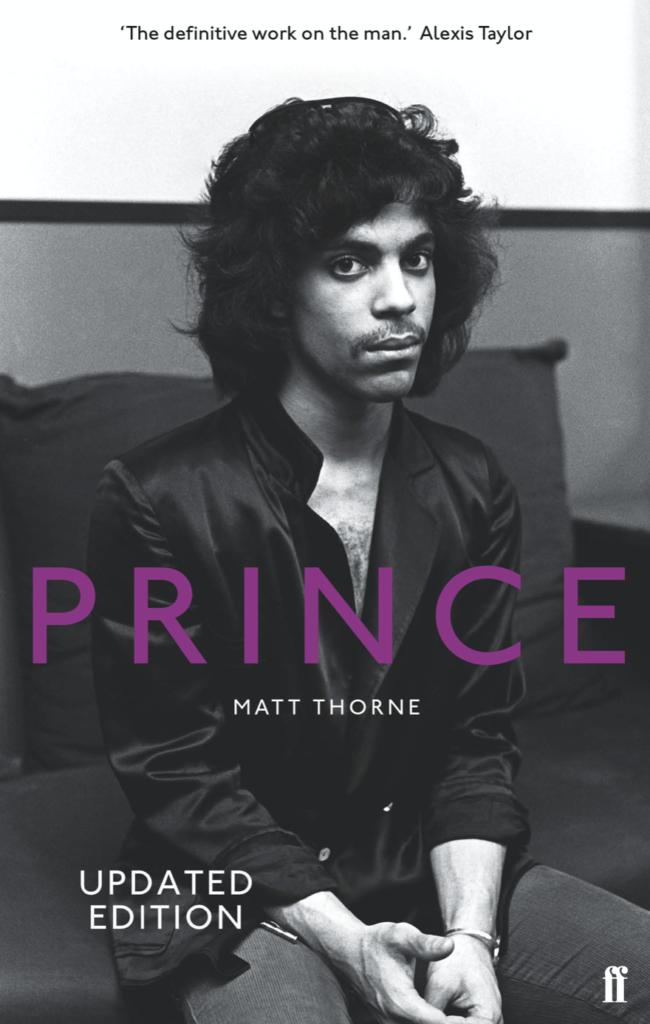

If you haven’t read Matt’s definitive book on Prince then go and grab a copy now!