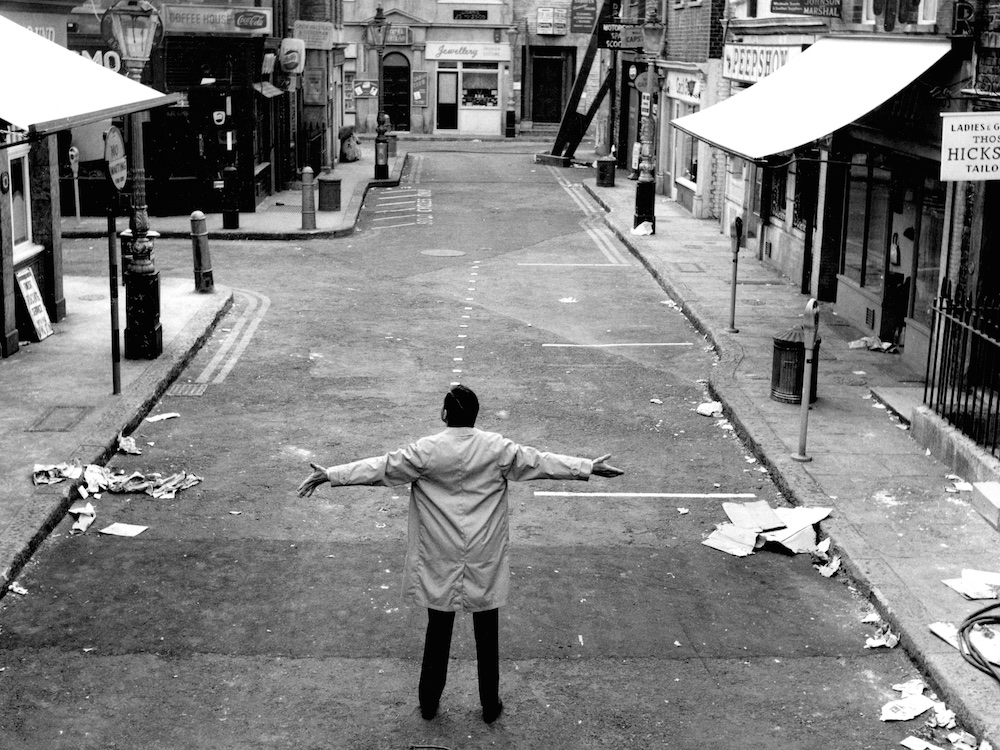

The opening sequence of Ken Hughes’ 1963 beat-crime masterpiece The Small World of Sammy Lee is a collage of tracking shots of an early Soho morning, set to an elegiac Kenny Graham jazz score. A cleaning truck hoses down empty market stalls. Newspapers blow about in the breeze. Pigeons flutter, then scatter. A series of restaurant facades: Asia Famous Curries, Choys, Chez Auguste, Isola Bella, Trattoria Toscana. A gas lamp, a brick workhouse, a modern high rise towering above. Red phone boxes and empty alleyways. Lisle Street in Chinatown, the Doris Café. Delivery vans and film posters. The Swiss Hotel and its Toby Ale. The Heaven and Hell Coffee Lounge and the 2is Coffee Bar. The Cameo Moulin cinema shows Naked as Nature Intended, the Nosh Bar, next door. The Lyric Theatre and the Windmill Revudeville. The Moulin Rouge Strip Tease Revue, Non-Stop Strip Tease, The Metro Revue Club. Metal dustbins spilling more newspapers. Empty milk bottles in clusters of twos and threes. Uniformed dustmen in caps and jackets smoke outside a peep show. One of them eyes up a young woman carrying a suitcase, and the film’s story begins.

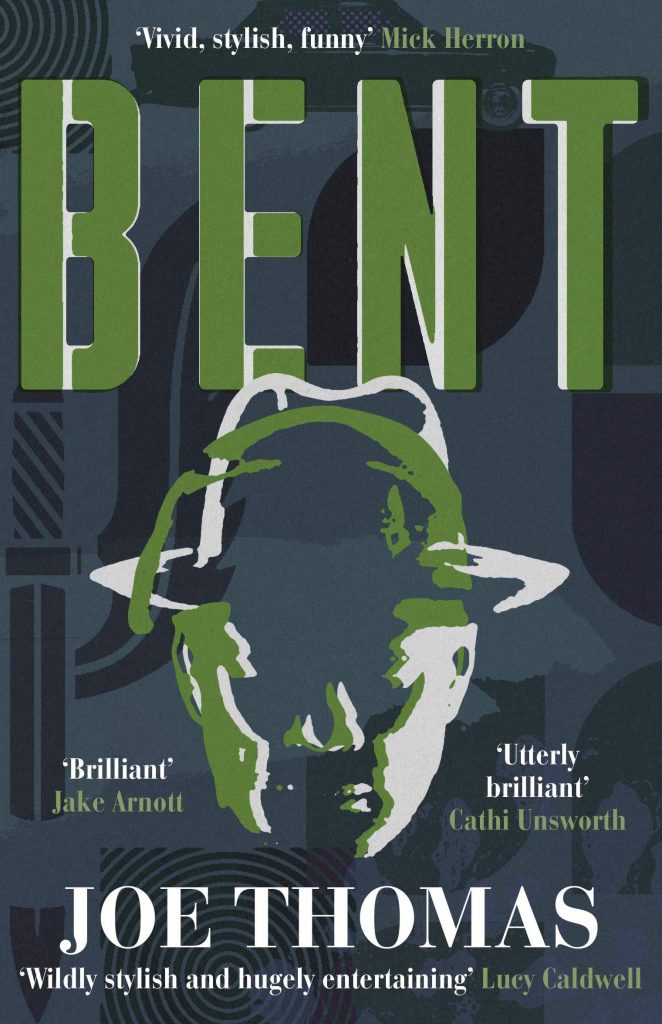

Some of the places in this opening sequence are still around, but not many of them. I first watched the film as research for my novel, Bent, set in Soho in the same year.

Bent is about Harold ‘Tanky’ Challenor, an SAS war hero, and ferocious and controversial Detective Sergeant working out of West End Central in 1960’s Soho. He once, on foot, chased Reggie Kray down Shaftesbury avenue and halfway back to the east end. The twins offered a grand to anyone who’d help stitch him up.

It’s easy to become nostalgic for Soho as its institutions are threatened.

In my novel, Challenor walks past the French House and the Three Greyhounds, talks about the Rolling Stones’ first gig at the Marquee, deals with the owner of the Phoenix and Geisha clubs, drinks brown ale and whiskey in an after-hours Coach and Horses session, a belt or two of Limoncello in Limoncello – and after that he’s thrown out of Trisha’s before he’s got halfway down the stairs.

I walked a couple of Challenor’s routes, to check facts and locations. If you look closely, most of the pubs have plaques on the wall by the door which tells you when they first opened. Another source on old Soho: an information board put up to hide Crossrail construction with descriptions of The Colony Room, The Academy, and Gerry’s, of the coffee bar music scene, and seedy vaudeville.

Of course, Challenor’s Soho is one I never knew.

Perhaps what Bent has in common with The Small World of Sammy Lee is the ordinariness of crime, or the fringes of crime. The lack of any glamour.

Fighting crime in Soho was, Challenor said, ‘like trying to swim against a tide of sewage’.

One evening, he was called to investigate a disturbance in a nightclub on Dean Street: glass everywhere, tables and chairs overturned. A young punter on a night out tended to a nasty wound in his eye. The proprietor, a known villain, sat at the bar.

‘What happened?’ Challenor asked him, nodding at the punter.

‘Fell down the stairs.’

Challenor took the punter to hospital; he lost the sight in his wounded eye.

One of the proprietor’s thugs was taken to West End Central police station in possession of a flick knife. After Challenor visited him in his cell, the thug claimed the knife was planted and that Challenor had given him ‘a belting’.

The following night, Challenor returned.

‘You’ve got porridge on your suit,’ Challenor said to the proprietor, meaning: it’s time you went to jail.

‘Uncle Harry,’ the proprietor said. ‘Why not let us sort this out amongst ourselves, eh?’

It was a protection racket dispute, one gang muscling in on another’s turf.

‘Tell that to the lad with one eye,’ Challenor said. ‘You’re coming with me my old beauty.’

It’s not clear what Challenor said or did to this known villain, or his thug – no charges were pressed – but there wasn’t any more bother over protection money.

Extract from Bent by Joe Thomas

The previous night Challenor went into The Coach and Horses via the lock-in entrance and proceeded to drink four bottles of brown ale and four whiskies very quickly.

He was halfway through his third bottle when someone clocked him, and there were a few murmurings, which he fronted out, and then a group dispersed as he purchased bottle number four, and then the same group gathered around him as he drank bottle number four and suggested he might want to leave.

Challenor remembers, now, staring at his desk, early, very early in the morning, that he wasn’t too keen on leaving.

Before leaving The Coach and Horses, Challenor swore violent revenge on at least half of the small group that had dispersed and then gathered around him to persuade him to leave, and then he put a chair through the window.

Well, he thinks now, with a wry grin – and this wry grin seems encouraging, he thinks, in terms of his imminent recovery – he didn’t put it through the window exactly, as the chair bounced back and landed, upright, ready for use, back inside the saloon. Challenor was not the only patron present to be surprised by this turn of events. The group that were gathered around him – two of whom had had to move sharpish to avoid this chair – stared in disbelief at the chair’s new position.

Challenor chuckles now at what happened next.

He, Challenor, sat down on the chair.

The group looked hard at the window.

Challenor sighed and smiled and waved his fourth bottle of brown ale at the bar staff, clearly desiring another.

The group looked at Challenor.

Challenor said, ‘Pull up a pew, have a seat, it’s bloody raining them, after all!’

The group looked again at the window.

Challenor said, ‘It’s not fucking rocket science, my old darlings!’

The window, it turned out, was open, and Challenor’s chair had in fact bounced back off the shutters which had been pulled down so as not to alert the long arm of the law to the illegal drinking that was going on.

Challenor smiles now as he remembers enjoying explaining that avoiding the police meant there was no damage. Had he, Challenor, not been around that evening, there would have been no need to pull down the shutters.

The pub was not wholly convinced by this explanation, by its logic.

Challenor did not stay much longer.

After he left The Coach and Horses, via the side door, he turned right, right again, and right again, to find himself back on Moor Street. While he had had a fair wallop of booze, he was smart enough not to return to The Geisha. He smiles at this foresight now, staring at his desk, his head smarting despite these smarts, his head bellowing, in general complaint.

Instead, Challenor barged into Limoncello, his favourite Soho trattoria, where his old pal Lucky ‘Luke’ Luciano was tidying away and chin-wagging with the staff. They were not, Challenor understands now, thrilled to see him. They were not at all tickled by his appearance, this was clear from the word go.

Their hospitality was brief, but significant: a bottle of the restaurant’s eponymous spirit was lifted out from behind the bar and several large measures were poured first into a tumbler, and second down Challenor’s throat.

Cheers, Algiers; Algiers, cheers! He remembers toasting the room with this to a general bewilderment. Challenor knew his friend’s game: sink him with fortified drink and he’ll be out of your hair all the quicker.

And Lucky Luke was right.

Challenor charged out of Lucky Luke’s charged up by a good dose of fortification, of fuel –

And then didn’t know what to do next.

It’s quite the problem in Soho for your drinker who isn’t especially keen on either live music or live ladies. Challenor likes music, he’s listening to it now, after all, he thinks, but he likes it on his own terms. Whenever he has tried to enjoy the live music experience, there have been moments of great pleasure, of euphoria, even, when he has been swept up in the rhythm, the swing, the sweet voice and the hard, percussive sway, when he’s looked about him and seen a joyous bunch of youngsters, face-splitting grins on them all, and he’s reckoned he’s understood this live music lark. And then he’s needed to go for a slash, and to do so has meant fighting his way across a packed dance floor, a packed, sweaty, writhing, jumping dance floor past a load of twelve-year-olds full of hair grease and he thinks, perhaps I don’t need this live music lark after all.

So where does your drinker go then?

Challenor tried Trisha’s on Greek Street. He got halfway down the stairs before the pair of berks who run the door picked him up by his arms and carried him back out.

‘Go home, Harry,’ one of the berks had said. ‘It’s four in the morning and we’re closed.’

‘Home? At four?’ he’d replied. ‘I’m going to work, my old darling.’