When we visit a place as a tourist or disciple, we often want to return with a part of that place, an aide-memoire, a memento that in future years will take on an almost religious power, reminding us of a time pregnant with possibility, new vistas, and the sense – ironically of course given the very nature of nostalgia – of being absolutely present and rooted in a moment of consciousness. We call those things ‘souvenirs’ and we carry them with us, through our lives, like religious artefacts. Strange little things that break over time (like Greek crockery) or fade (like a cheap postcard from Mallorca) over time. When we die their meaning either evaporates, or if through some act of magical transference the object’s significance has been passed on to a son, daughter or friend, it takes on new meaning; this time invested with the very spirit of ownership of the departed.

We invest meaning in things as markers to make sense of our past, like Hansel and Gretel in the forest. Souvenirs define us and as collectors of music and books (at least at The Social and White Rabbit) they become time capsules; the initial and immediate joy they gave us turned into indicators of mortality and grief as they grow battered and sometimes ignored. Like the discarded toys in Toy Story, they gather dust and the exhilaration of play and abandon they once represented, turn melancholy. Souvenirs are memory. They are also human fallibility. They are things but they also represent how life cannot be captured, only lived. It is in the nature of things to expire, but we desperately want them recorded.

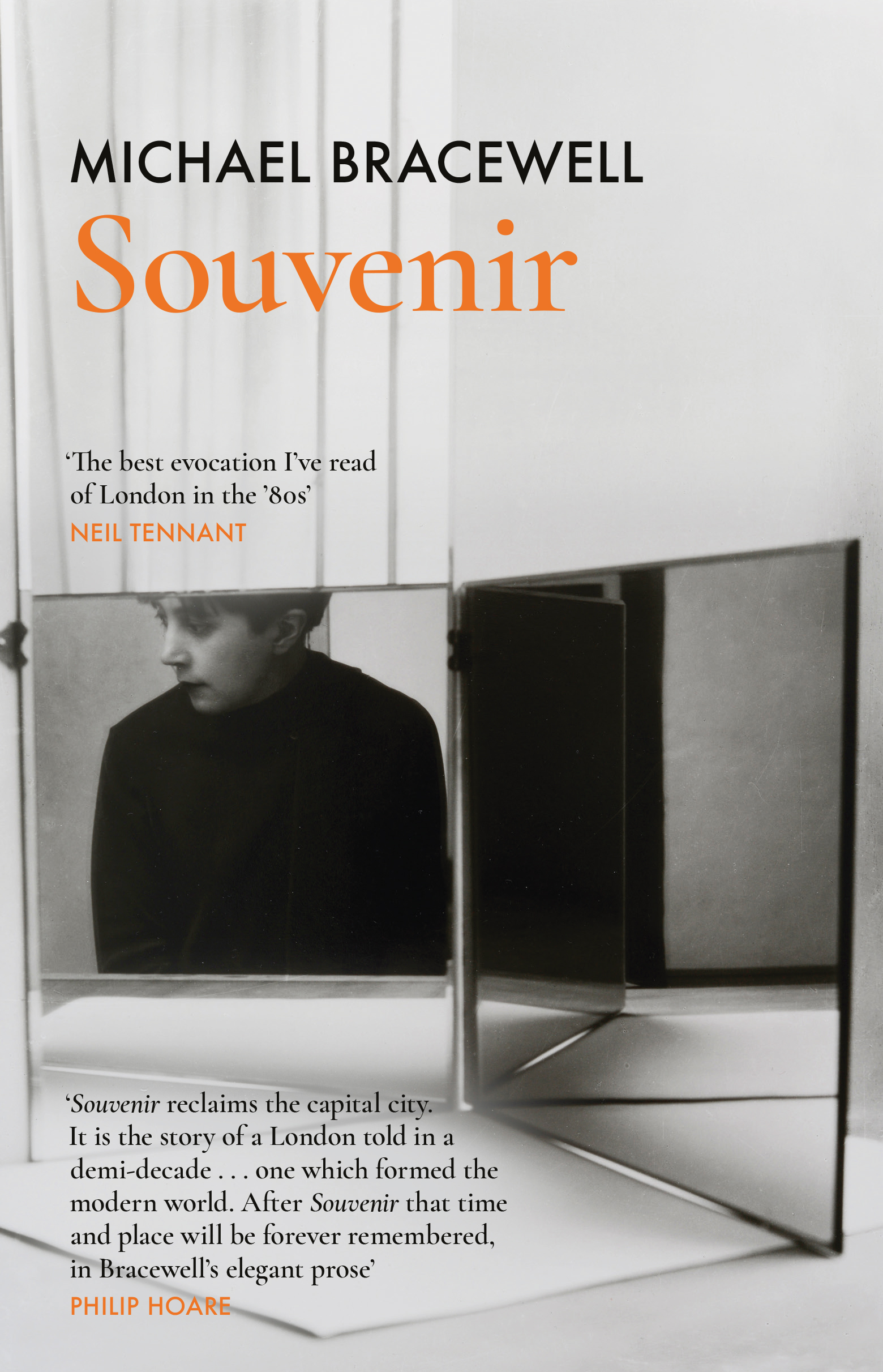

Michael Bracewell’s alchemical new work of non-fiction, which often reads like fiction, is a paean to early Eighties London, a world now mostly disappeared, bulldozed and forgotten. The music, the clothes, the boys and girls with their High Modernist Minds. It is a book that explores the nature of memory, the artistic licence of it, and the last glories of a pre-digital age when things were invested with the occult power of souvenirs. It is a remembrance of things past for a world that is now off the map and only accessible in a reverie. It is a book by a writer who understands the power of literature and art to make us humble in appreciation of our youth, the abandon and intemperate times we indulged in. We are delighted to share a first extract here from Souvenir, by a writer with a style and vision entirely his own, Michael Bracewell.

Lee Brackstone

Blax, Sicilian Avenue, WC1 – dressing like a Vorticist

A sound like ice cracking; a new softness in the air, pushing back the edge of the cold. Hyacinth days. The afternoon light lasts longer; grey-blue streets at 6 p.m.

At Holborn – neither West End nor City, but with something of the mood of both – the diagonal precinct thoroughfare of Sicilian Avenue, in the spring of 1983, clipping a corner of Southampton Row, has its own air of hidden splendour: a flourish of European elegance circa 1910, in this ornate, many-pillared spacious avenue of peach-copper brick bay-windowed mansion flats and turret rooms, rising four storeys above what seem exquisite emporia, or transmissions of same across seven decades.

Through Holborn and the Bloomsbury squares one had time-travelled, Kraftwerk on the Walkman, to what felt like vivid contact with the cities of the old Imperial civilisation of Europe, pre-1914 – ‘we stopped in the colonnade, and went on in sunlight . . .’ And with something coming that hates us; but for today, at least, the pink buttonhole, the cinnamon-brown suit, the silk tie flecked pale blue; ‘and drank coffee, and talked for an hour . . .’

In 1910 – Wyndham Lewis meets Ezra Pound at the old Vienna Café; there in the wedge formed by Hart Street and Holborn – and, along with the Café Royale, the only truly continental café in London: ‘. . . had the tarnished polish’ (wrote Lewis) ‘of the most gilded cafés of five or six continental capitals . . .’; it’s passing later lamented by Pound:

in those days (pre-1914)

the loss of a café

meant the end of a B.M. era

(British Museum era)

The end of an era . . . Milan, Warsaw, Berlin, St Petersburg, Paris, Brussels – Trans-Europe Express – already extinct these last seventy years; but we catch their mood like a ribbon of cologne or cigar smoke on the softening breeze; the chamber theatres of their defining service industries – shoe shops and barbers and tobacconists, fancy confectioners, silk scarves and outfitters, department stores, restaurants deluxe, grand hotels, ubiquitous dusty fronded palms – still there, or rather, somehow, here, in London WC1, in glimpses, in the early 1980s.

Phantasms of modernism, erratic fragments left by the glacier of time, preserved, ghost shops linger in the modern daylight, and are now best employed as ready-made film sets for the imaginary films being made by and starring – in their heads – young people of a certain disposition . . .

European modernism – its received idea, its reach to New York and the Midwest even – has seemed attuned to the twilit deep midwinter of post-punk, part of that map, and now it’s here still in the sense of a spring’s earliest gathering, as the span of seven years can be described by four seasons.

Preorder Michael Bracewell’s Souvenir now