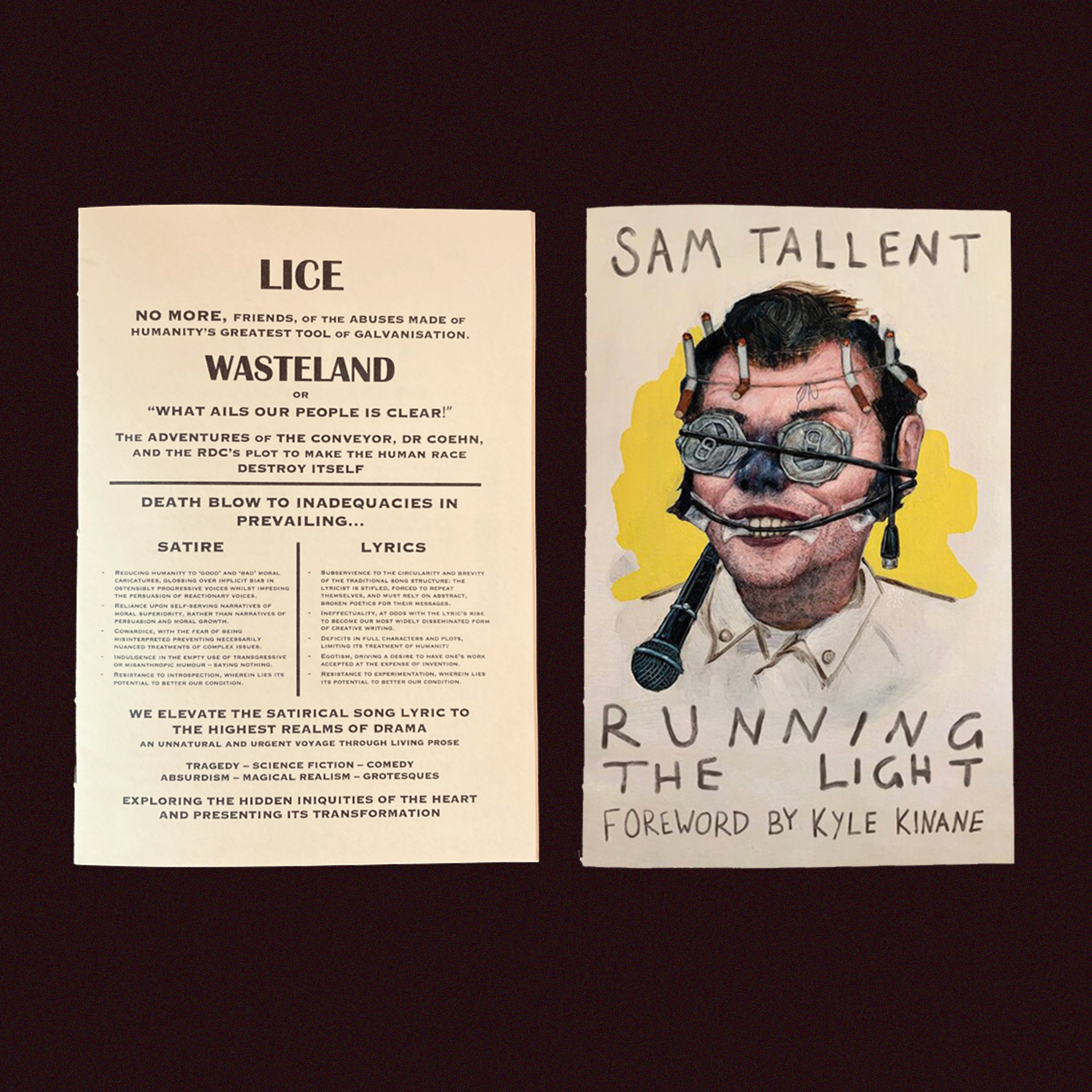

Running The Light is the first novel by Denver stand-up comedian Sam Tallent. Electrifying the wider comedy community since its self-publication this year, Doug Stanhope recently called it “the best fictional representation of comedy in any medium”. The story follows the washed-up, thoroughly ruined but occasionally-brilliant aging comic Billy Ray Schafer across a string of crushing gigs through the American South West, as he navigates the demons of the comedy circuit and attempts to make peace with his long-estranged family. Heart-breaking, hilarious and deeply rattling, it is a conflicted and brutal portrayal of life as a stand-up, eerily interwoven with the real world; Norm MacDonald, for example, is written into it as a major character.

This unique and powerful book came to me at a poignant time, following my own prolonged interrogation of the circuit I’d spent my early twenties performing on. After two years of writing, my band LICE had finally completed our debut album WASTELAND: What Ails Our People Is Clear. A concept album, the lyric pamphlet is a prose story melding sci-fi and magic realism, arguing that by unsettling the conventional song lyric, satirical music can better explore implicit forms of bias and iniquity. Following a vigilante in a strange liminal space populated by time-travellers, talking genitalia and more, the prose transforms with the characters’ moral stances: warping into cutups, soliloquies and plays. The album was inspired heavily by my disillusionment with the landscape of satirical music: the ‘punk world’ I’d once been inspired by, but now found broadly toothless, vague and self-serving. When I read Running The Light, seeing flashes of a similar conflicted impulse in an art form I’d never even attempted, I was floored.

Seeing Sam’s email address listed on the back cover, I decided to reach out saying how much I loved the book. It turned out that Sam was not only a LICE fan, but had played in a punk band himself prior to taking up stand-up comedy. I shared WASTELAND with him, and so began a wonderful new friendship. When The Social Gathering contacted LICE to talk about our new album, it gave us the idea and the opportunity to speak at length.

We here present a two-way interview between myself and Sam Tallent, discussing our respective portrayals of stand-up comedy (Running The Light) and punk music (WASTELAND: What Ails Our People Is Clear), and the relationships between these often-similar worlds.

SAM: I’ll go first. This album dude – I know that you’re young and you don’t know any better, but it’s very impressive. It makes me think of being young and listening to Fucked Up on headphones in a flatbed truck, wasted. I don’t think you guys arranged this, I think it’s more like it was masterminded. It reeks of all this confidence, but without being arrogant. It’s like ‘trust us – we know what we’re doing’. You have the pamphlet to go along with it, you’re starting this label… my question is, where did you get all this confidence from?

ALASTAIR: LICE formed in Bristol, which is the centre of a lot of really explosively imaginative and forward-thinking, difficult music that we were always really inspired by, but the music industry in the UK is completely London-centric, and Bristol’s music isn’t really monetised. It’s all DIY. So, we were always surrounded by these people that were making this music, but having to be aggressively entrepreneurial with it…. They had to rely on confidence and this really great community, because ‘the industry’ wasn’t going to do it for them.

SAM: I know what you mean. We’ve got L.A., we’ve got Chicago, we’ve got New York… For so long, if you didn’t live in one of those cities you weren’t a ‘serious comedian’, so Denver had this huge chip on our shoulders. “We’re funnier than all you guys! Come here, let us open for you, we’ll bury your ass!”. We had to do everything ourselves. Start our own shows, book our own shows…

ALASTAIR: Yes! I mean you populate ‘Running The Light’ with all these references to the real comedy circuit, and allude to how comedians in some respects operate in these small circles. I was going to ask how important you’d say community is to your experience of being a comedian?

SAM: Hugely important. When I started off doing stand-up, me and my three best friends ran a weekly show. When the comics who were ahead of us had a more famous or successful person in town, they would tell them to do our night too. If you’re funny, and you’re nice to them, then when you go to New Orleans or Austin you can hit them up about shows. Once they book you, you’re sleeping on a stranger’s floor and eating breakfast with their kids. That’s what I miss in this time – I have friends in every city in America and all over Canada, and I don’t get to see them. Usually I’d be in their town once a year or twice a year. I’ve let so many strangers that have been ‘vouched for’ sleep in my house where my wife and I live, and it’s just because somebody told me they were legit and they’re funny – and that favour’s been more than paid off.

ALASTAIR: Running The Light gave me a real appreciation of how much this profession demands of the people that make careers out of it. It’s a pretty raw look at the ugliness that’s possible in the stand-up world, which in many ways connects with my experiences of the potentially ugly side of the live music circuit. However, I did read the book as, in some ways, a sort of love letter to stand-up as an art form. Given that conflicted representation, were you worried about how it might be received within the comedy community?

SAM: I was worried that comics wouldn’t like it – not because I skewer stand-up, because every comedian knows this guy. There’s a comic like this in every city in America: this old, broken-down dude that you’ve heard is the funniest guy ever, and when you meet him he’s this shaky-handed drunk that can barely talk unless he’s onstage. I was just more worried that people would think I was being pretentious, because my stand-up’s so silly and goofy.

I completely counted on stand-ups and fans of stand-up to embrace this book. That was my whole pitch to the literary agent (before I decided to not use one). When you hear a bunch of comics say “this is the best representation of stand-up comedy in fiction” you think “damn right it is!”, but also “thank you for saying that, because I was so worried people thought it was me trying to show off”.

ALASTAIR: How long has that been an aspiration to write a book about comedy then?

SAM: I just always read a lot. I love literature. I love Graham Greene – have you ever read Brighton Rock? Come on brother! There’s a lot of really great authors I love from the UK, like Graham Greene, Irvine Welsh, Cynan Jones – do you know that guy?

ALASTAIR: No I don’t!

SAM: He writes all about dog-fighting and badger-hunting – you should check out The Dig. I never really aspired to write a book. I wrote short stories and I read a lot. It was a good creative outlet and I kind of realised I was good at it, and then I lived alone in Las Vegas: the cultural hellhole of America. My wife did her first two years of medical school there, and I was alone, missing my community in Denver, just in front of the computer writing this book.

ALASTAIR: How long did it take you?

SAM: 18 months, four or five days a week. So, I’ve got one for you. That pamphlet is really cool. In ‘Folla’, that’s where you introduce the crowd – that refrain “THE CHARACTER OF THE CROWD IS INTRODUCED”. How do you feel about the crowd? Do you care about the crowd liking what you do, or is it more like “hey we’re going to do what we do, and you’re going to like it?”

ALASTAIR: In the early days we were hugely inspired by artists that were very antagonistic and confrontational, but spending so much time in support slots for big punk bands… you’re just grateful to be there, and spending so much time playing to people that weren’t our crowd took the edges off us a bit. Over time though, we were becoming increasingly disillusioned with the ‘punk world’. When we starting playing this new stuff, like ‘Imposter’ which opens with a two or three-minute industrial intro, you look at the crowd and realise nobody wants this – they want riffs!

SAM: Like they have no patience for you guys trying to freak it out a little bit.

ALASTAIR: Exactly. You come to resent aspects of it. That led to this kind of second wave of more deeply-held frustration that made us a confrontational band again. It was always tongue-in-cheek, but I’d go onstage and just rip into people for reacting a certain way. As this album became fully-realised though, it became about going “this is great. You should like this. Please come along with us and enjoy this.” Now I see the crowd in terms of people that have come across us through the punk world and go “this isn’t for me”, and the people scattered amongst them that dig it.

SAM: I feel you, because Denver comedy was founded by Boston comedy, which was very confrontational: “shut the fuck up and listen to me”. I like that in music too. My favourite bands, Black Flag, Big Black and stuff, are like “we’re not what you want but we are what you need”. The thing is though, when you’re young, playing music or comedy, is there’s that tendency to be confrontational, which I remember as being a defence mechanism. I remember being at this big open mic in Denver, and if you were funny there then you were ‘anointed’. I remember being so afraid to do my act there, I would crawl along the top of the booths and bounce the mic off of people’s heads. I’m 6’5” and 300 pounds, so I would physically be a bear of a man looming over them. I wanted them to like me, and if they didn’t like me, I wanted them to be afraid of me. I really respect the fact that you guys let your art speak for itself – that’s a big step.

ALASTAIR: On the subject of maturing, what would you say the major differences are in the circuit since you started doing comedy?

SAM: When I started comedy, I loved the fact that you were surrounded by freaks and weirdos: people that couldn’t exist anywhere except stand-up. Stand-up changed my life, and in some ways saved me, and I loved hanging out with these pirates that just couldn’t be part of polite society. Now there’s a lot of cool, pretty kids who aren’t funny, and through the magic of social media they’re able to be anointed as ‘what’s next’… but I’ve seen their act, and they don’t have ten minutes. Let them do their cute, precious, cloying comedy in New Mexico for people who worked 80 hours that week, and they’re going to be eaten alive. I miss the days when outsiders and freaks could do this. It’s better now because it’s safer and I’m glad it’s moving that way, but I miss when stand-up also had to be funny. I don’t want to sound like I’m not progressive, because I’m incredibly progressive. I’m an anti-capitalist, and I used to be a brick-throwing anarchist – when I was a kid in my band, I moved to upstate New York in the woods. The band was called Red Vs. Black because of the anarchist flag, and I lived in an anarchist commune and stuff. I want everyone to be free, but I also want you to be a comedian.

ALASTAIR: It sounds like there’s a similar kind of disillusionment to what WASTELAND deals with, where you look at the landscape around you and there’s people getting away with murder…

SAM: Without murdering! I come from the background in Denver where you have to kill or you don’t get booked. I’ll do auditions for big comedy things and I’m there with a bunch of 22 year-olds who twerk to Baby Shark as their closer. I’m pacing like an animal backstage around these children with a hundred thousand Instagram followers and… I want to destroy them!

ALASTAIR: On that note, something Running The Light really compellingly captures is the experience of live performance, but also all the stuff around live performance: coming off stage, going onstage, deflation, boredom. I’ve not read anything that talks about performing so exhaustively in terms of the bits that aren’t performing. What inspired that?

SAM: It’s cool when you’re in a band, because you’re there with your bandmates, but in comedy you’re alone. You’re in a city you’ve never been to and you’ve got 24 hours to kill. Being a comedian, a lot of it is preparing to go onstage and figuring out what you’re going to do up there. Either you have a great set and you feel like you can rip God from the sky (and then you try to numb it with booze, or sex, or food), or you bomb and you want to kill yourself and everyone in the room. I don’t know how you just go to bed after doing stand-up very well: that’s where the six beers come in, or you go to the diner and eat fifteen pancakes. Once you’re done, you’re just another person – you were the best thing to happen to that room, now you’re another turd in the bowl. I think writing about stand-up, you have to talk about that stuff…

ALASTAIR: The shifting merch afterwards…

SAM: Is there anything worse than having to sell merch after you bomb?

ALASTAIR: God no. People filing past you…

SAM: There’s a fun phenomenon in stand-up where you’re at the back of the room next to your opener. You’re shaking hands and selling merch to the crowd, and they’ll come up to you and say in front of you to your opener “you should have been the headliner!”.

ALASTAIR: That’s brutal.

SAM: You’re damn right it’s brutal. I mean, let me ask you about that. I knew about you through IDLES because my YouTube algorithm brought up your guys’ stuff. How much pressure do you guys feel escaping the shadow of IDLES? Because when I open for Kyle Kinane or Doug Stanhope and the promoter comes up and says “we’d like to have you back to headline”, that’s what I was trying to do.

ALASTAIR: Our relationship with IDLES is interesting. When we showed up on the scene, IDLES had been going for years and their first EP did terribly; to all intents and purposes, they were pretty washed up. I met and interviewed them for the student paper at one of their first sold-out hometown shows, and we’ve just watched them ascend since. At this point, they’ve had a Number 1 album and they’re the biggest punk band in the country.

So, we’ve always seen them very much in terms of them having to work to get that good. We did this tour with them in April 2018 and the first show was at this huge old theatre in Bath called Komedia. We went onstage, did our thing, and came off high-fiving each other thinking we nailed it. Then we watched IDLES obliterate the stage. I remember watching this and thinking “how much have I really learned, in two years of doing this?”. Opening for them became kind of a learning experience. For example, Joe had just gone sober. As you know, the first thing that happens when you play a show is the promoter goes “here’s beer tokens” or “here’s a crate”.

SAM: Exactly, it’s how you get paid mostly at the beginning.

ALASTAIR: But this time I decided to try this whole run of shows not drinking at all. Initially it was terrifying, but then it was incredible. However, after we released our old stuff on IDLES’ label Balley Records, so much of what we became concerned with artistically was asking “why be a punk band?”. The stuff that saturates this current moment in UK punk music is so conservative and cowardly. Stepping outside of IDLES’ shadow has in some ways been really aggressive – going onstage and, while obviously being a punk band, slagging off punk music.

SAM: Well yeah that’s punk rock! That’s exactly what it is.

ALASTAIR: Playing those supports with IDLES or with Shame, we were also always trying to find a few people amongst those crowds that might get us. Now that we’re doing our own thing on our own label, with nobody to answer to, and it’s like “okay – let’s see who we managed to filter out!”. We did our first headline tour this year and it was – perfect. You look at the crowd and think “this is all people who have come specifically to see this”. But yes, those support slots were definitely a learning experience.

SAM: That is cool, when you think you’ve got it figured out and see someone that makes you think “I don’t know anything”. When I would open for Kyle Kinane, who is one of the best stand-ups working over here now and like my hero, I was coming out swinging trying to impress him. But I was also kind of burying him, and he would talk about that on podcasts. The next time I went out and opened for him, I came offstage joking like “follow that old man” and I’d watch him go onstage and just be a master. And you’d think “yes – that’s the guy that I fell in love with 11 years ago”. That’s a really good feeling, to be reminded of that.

ALASTAIR: Have you ever been upstaged the other way around?

SAM: I’m lucky that I’m in a position now where I can choose my openers. America’s really, really big, and there’s a lot of places in between the big cities where you would not want to spend an hour, so when you have the opportunity to play there with someone you think is funny but also genuinely love, it’s so much better. But then you’ll do the late show Saturday night, and just be thinking about your cheque: “I’ve done five shows, I’ve got to get out of Cincinnati and go home and see my wife, I drank too much for 4 days, I’m not getting enough sleep”… and every now and then, one of these kids will hand you your ass. So yeah dude, it’s always good to be reminded you don’t have it all figured out.

Let me ask you something. You guys have a lot of cowboy imagery, and even ‘Imposter’ has that gallop in it. I’m actually from the West, cowboy town: I come from a small town in the plains where we would have dances on Saturday night, and my Dad would dance to western swing and two-step. Where does this affinity for cowboys come from, this Western fetishism?

ALASTAIR: Do you know a band called The Country Teasers?

SAM: No.

ALASTAIR: They were this Scottish band in the ‘90’s led by this guy called Ben Wallers (aka ‘The Rebel’). So much of my stuff is reacting to things I don’t like in lyrics, and I don’t have many heroes, but Ben Wallers is definitely one. The Country Teasers’ bag was employing Wild West imagery and country music in these post-punk records. Ben left the band, and has ever since been an assistant manager at a garden centre. Around the time we started LICE, Fat White Family talked in pretty much every interview about this guy, and as a result The Country Teasers became massively repopularised. There’s a band called Goat Girl whose first single made reference to Ben Wallers, and suddenly there were loads of others trying to do that C&W thing. If you’ve got this image of really exaggerated white western culture, using that as a vehicle to satirise racism and bigotry becomes interesting. It became this huge thing. We played early shows dressed as cowboys, but we went to London and everyone was doing that as well. We’d play with a Glasgow band called Sweaty Palms, and they’ve got cowboy hats. Tiña, Sleep Eaters… it’s huge now. The guy who did our early artwork using that imagery is from this noise band you’d love called Spectres.

SAM: I know them!

ALASTAIR: No way! Yes, it’s the guitarist Adrian Dutt from Spectres.

SAM: Ah that’s sick dude.

ALASTAIR: How do you know them?

SAM: So my little brother is really, really cool. He’s the one who did the design for my book, so he’ll just send me cool stuff. He turned me on to Spectres, and – there’s a band over there called Sleaford Mods? It makes zero sense at all that they’re popular. There’s a lot of cool stuff over there that makes zero sense to me.

ALASTAIR: So Running The Light is really funny, but alongside framing comedy as this alchemy, it points to the potentially pathetic or debasing nature of performing to entertain people, capped off by the scene where Billy Ray drinks honey mustard. How did you go about writing those stand-up sequences?

SAM: A lot of that is stuff I’ve done in situations where my act wasn’t working. My favourite sets are where I don’t have to do any of my jokes. If I can do 45 minutes of improvisation and crowd work, that rules. But, there’s a thing comics call “smelling like the road”, where you start doing hacky crowd work. I wanted that to come through with him, where he has flashes of brilliance, but he’s been on the road so long he forgets what’s good. I wanted him to sound like he was trying to do what he had to do to survive.

But then there’s that set where he bombs in front of Norm Macdonald on Saturday night, which ends up being insightful. He’s talking about his life, and his greatest failures, and how ashamed he is, and he thinks this comedy sucks – I like that. It was easier to write the bad comedy because I’ve seen (and done) a lot of very bad comedy, in places that didn’t want to see comedy. It was hard to write that long piece, because I wanted to walk that line: does he have the self-awareness to put these thoughts together in a way that’s poignant and funny?

ALASTAIR: That’s one of the things I loved about the book, but also found heart-breaking about it. You’ve got the inner monologue where Billy Ray’s reconnecting with his son and comes up with all the perfect things to say, and then he talks aloud and bottles it – that actually happens a few times.

SAM: I think we all have those ‘abracadabra’ moments. You think you have the magic words, then you get in your own way and you’re just screaming at someone you love.

So, I’ve done every state in the United States, and you know what you’re getting into. I’ve only done stand-up abroad in France – I crushed the first show in Paris, and the second night I bombed. What’s it like for you to play abroad? Because that’s so cool you’re in the UK and you can go play Europe, but I would be terrified to play these places where there’s a language difference.

ALASTAIR: Honestly, it’s the best thing in the world. In an incredibly oversimplified way, our take on foreign audiences so far is they are so much more receptive to new stuff. When we play in the UK, people come to see songs they know and you build the set around that; if you play a new one, it’s always semi-apologetic. We started playing Europe when we started writing WASTELAND, so we’d play a new one like ‘Conveyor’ and people would go batshit. I suppose from a promotional standpoint you can pitch it as an ‘English Invasion’ – like it’s exotic.

SAM: Let me ask you this. London’s super cool right? It’s like the hub of culture, and if you live in London you’re a cool guy right?

ALASTAIR: Don’t believe the hype. It’s full of douchebags and terrible, terrible music.

SAM: Well here’s the thing. When I go to L.A. or New York and do shows, everyone there thinks they’re super cool and they don’t need to prove anything. When I’m in Omaha, Nebraska, people there are so excited to have something creative and original come to town. Do you find that?

ALASTAIR: Definitely. We did this run once where we played shows in Milton Keynes and these really small, off-the-beaten track places where you’d think “how does this place have a music venue in it?”. You get there, and people freak out there because it’s an event. Local openers tend to be better out of the ‘central hub’ too.

SAM: They try harder. So, let me hit you with one more. I read that pamphlet on my phone, and it’s very clear that you guys are funny people. Between UK punk and American punk, Black Flag couldn’t have been more humourless (though Henry Rollins thinks he’s funny), but you had the Sex Pistols and Eater, and they were always funny bands. Why do you guys allow yourselves to be funny over there when American punks don’t want anyone to think they’ve said one funny word in their life?

ALASTAIR: That’s really interesting, and an observation I’ve not heard made before. If I were to pull something out of my ass, I’d say maybe because in the UK, what’s really popular over here like Stewart Lee…

SAM: I was about to say Stewart Lee!

ALASTAIR: Exactly. From Stewart Lee (who is a genius) to all these hacks, there’s this pervasive, often-caricaturised ‘British’ culture of using humour in the context of frustration (and specifically self-frustration), grimness, bleakness etc.. Music I know over here that tries to be funny comes from that same place. I guess it’s easier to reconcile that accepted kind of humour with aggressive or ugly music.

SAM: I think it’s just because you guys are better at talking, because you’ve been speaking English longer.

ALASTAIR: Ha! Well I’ve got a rounding-up question for you. Norm Macdonald features very prominently in the book as a voice of reason. However, he also serves as, I suppose, a glimpse of an alternative path that Billy Ray’s life could have taken. Throughout the book there’s those heavy questions of morality, and how these impulsive decisions that pervade the book can be explosively destructive. What would you like people to take away from Running The Light?

SAM: I would like people to take away that they read a book and they liked it. A lot of people have read this book who haven’t read a book in a really long time, because they were fans of me or people that recommended it. I do hope this book fits into the canon of literature – there’s prose in there, and I want it to have all the hallmarks of a book that might be taught in an English class – but I don’t want people to be intimidated by books. You don’t have to read Moby Dick, you can read Fight Club. I’m not trying to be falsely humble or eschew any kind of artistic credibility – but sometimes a book’s just a book and you enjoy it, and that’s totally fine. Real quick, what’s your favourite book?

ALASTAIR: Of all time? The Sirens Of Titan by Kurt Vonnegut Jr. Are you a fan?

SAM: Yes I love Vonnegut. When I lived on that anarchist compound it was in Ithaca New York, and he used to write above this bookstore there. I guess he only smoked Pall Malls, but you’d go there and they said if you try to light any cigarette that’s not a Pall Mall, you won’t be able to get your matches lit. We tried it out, and – I swear to God – we couldn’t get any matches lit with Marlboroughs or Camels, only Pall Malls would work up there.

ALASTAIR: That’s incredible.

SAM: Vonnegut rules. Yeah, you guys have the spoken-word but we’ve got the written word… so suck it!

Order Sam Tallent – Running The Light

Read LICE – WASTELAND: What Ails Our People Is Clear