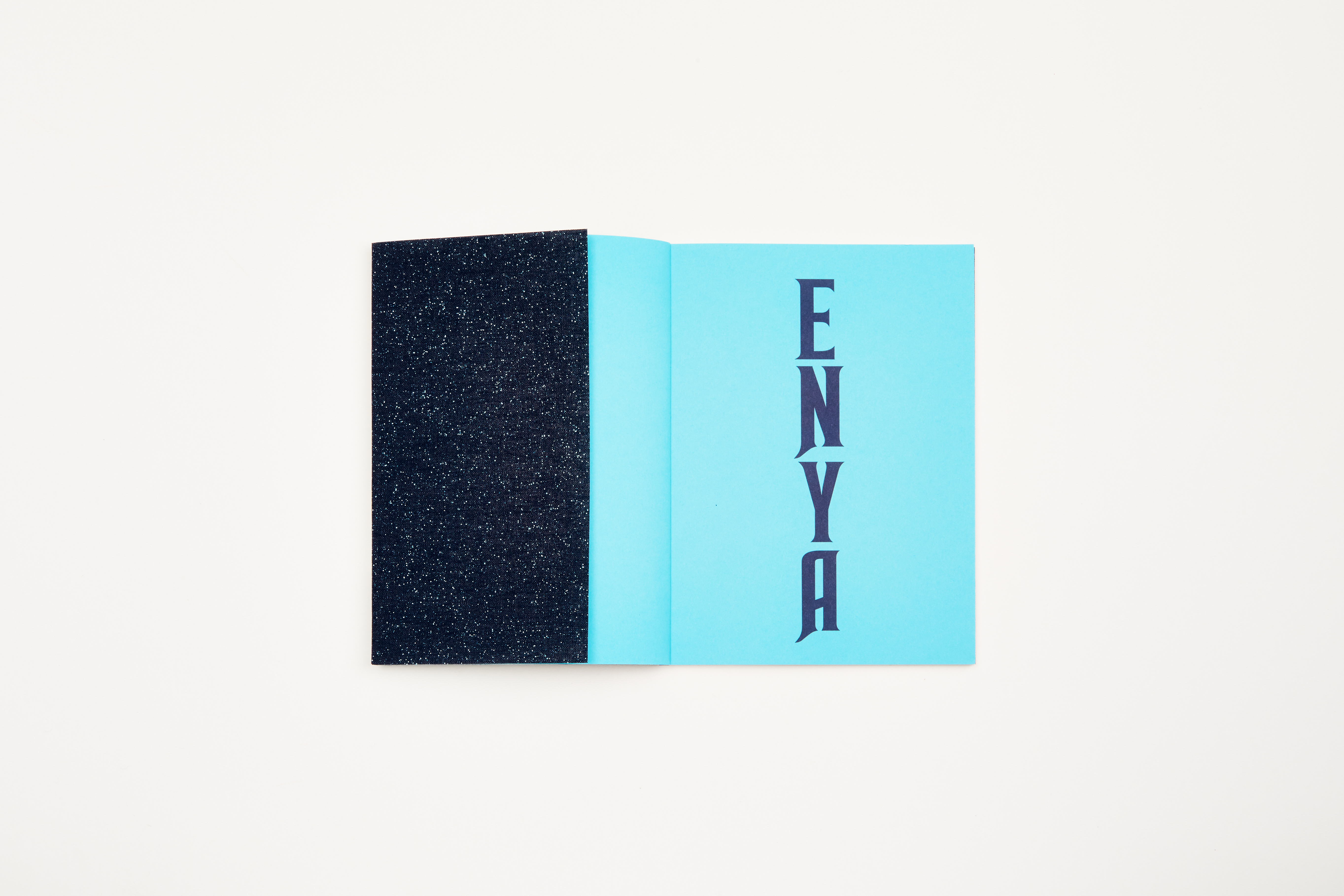

It was ages since I’d read a treatise on something. Too, too long. So I was holding one in either hand, weighing up what to get: the Scottish Enlightenment philosopher David Hume’s 1739 A Treatise of Human Nature, or the one by the Grammy-winning, Canadian musician Chilly Gonzales: Enya: A Treatise On Unguilty Pleasures. I hesitated for a while but in the end, the tug of the beautiful little book with the spangled glitter cover was just too strong. (This wasn’t the Scottish Enlightenment classic, by the way, although I’m not saying a glitter cover wouldn’t also work for it, as a concept.)

Enya is a book so affable, so personable, so far from scholarly froideur, that you wish the writer, when dealing with the complexities of musical pleasure and taste, could be right beside you, so you could say, I know what you mean!…tell me more about that…yeah but is that always true?…let me tell you about the first record I ever liked! Gonzales talks about how musical taste begins as involuntary reaction, an auditory goosebumps, citing his own childhood appreciation of Billy Joel as an example, but how, over time, this transmogrifies into something more studied, wilful and akin to self-definition: ‘I re-imagined who I wanted to be. I started to retro-fit my musical taste…went into hibernation and re-emerged…as a guy who listens to Pavement. Fuck that jazz, fuck that soft rock, fuck the Bee Gees.’ The concept of ‘cool shit’ emerges.

When kids get tired of wondering whether Batman can beat up Superman, a natural progression is to consider whether the Beatles are better than the Velvet Underground. (I have happy memories of being a loyal listener of a radio programme called Battle of the Bands where utterly random groups – Steely Dan vs The Human League, say – were pitted against each other for listeners to have their say on who should reign supreme.) Gonzales reminisces about a night with some friends when they ended up ranking iconic musicians from best to worst. One of them eventually asked the question: ‘Are we talking about quality and important to the history of music, or just my taste?’ This friend hit on one of the key divisions explored by Gonzales: there is a canon, consensus, even shared ideas of shallow vs deep music – and then there is what an individual actually likes. A means of integrating the two is to introduce the idea of the guilty pleasure, accommodation through irony. Save yourself the embarrassment of falling for ‘lowest common denominator vulgarity’ by smirking while listening: ‘I fucking love it. It’s so fucking bad.’

However, Gonzales fucking loves Enya because she is so fucking good. The artist with 80 million album sales is a resolutely unguilty pleasure. He appreciates her ethereal and pure voice, her signature sound of fake synthesized string plucking, her rejection of beats in favour of the ‘single grand gestures of symphonic percussion’. He considers her less a modern-day singer-songwriter and more a 19th century Romantic composer. The pleasure that he has had in her music is nothing new. As a teenager he sat with his D-50 synthesizer playing the ‘Sail Away’ chords – ‘master of an entire orchestra, feeling both modern and ancient.’ There is no smirk about any of this.

But really, this isn’t a book about Enya. It’s one about Gonzales and I am glad about that. He quotes Ted Hughes talking about how artificial limits can be useful in getting things done if you are a writer or whatever, and so, with Enya as a kind of glorious and adored constraint, Gonzales has written a musical memoir. And it is a lovely one. He’s the teenager, bingeing on jazz fusion when other kids are smoking weed. Downbeat magazine, the jazz nerd bible, is his porn. He’s the young music student, whose teacher is telling him to listen for the space in John Coltrane, the place between phrases which he can fill with his own emotional reaction. He’s the piano player in Berlin, providing background music in places as diverse as a Bavarian sausage restaurant, a hotel bar, and a lingerie shop. Typically, he doesn’t dismiss this as a lesser activity. No: ‘I was part of sacred activities: meals, clandestine meetings, the trying on of underwear.’ And then of course, he is there, centre stage with his own music, there as a collaborator with the likes of Feist, Peaches, Daft Punk, Jarvis Cocker.

Gonzales talks about how creating music is to some extent a curative activity. It can help ‘fill the void.’ But others’ music can do that too – thankfully, for those of us unable to produce a note. ‘The songs I turn to in trying times,’ Gonzales writes, and he is thinking specifically of Enya’s, ‘are the background music of filling the void, the original score to the movie of my life.’ Beneath the glitter, a careful and frank introspection moves through this book.

Little bonus: the epilogue is brilliant.

Words: Wendy Erskine

Photos: Beth Davis

Enya: A Treatise on Unguilty Pleasures is available now from Rough Trade Books – BUY HERE

Event: Chilly Gonzales in conversation with Laura Barton on Thursday 10th December, 7pm – MORE INFO